Copyright brisbanetimes

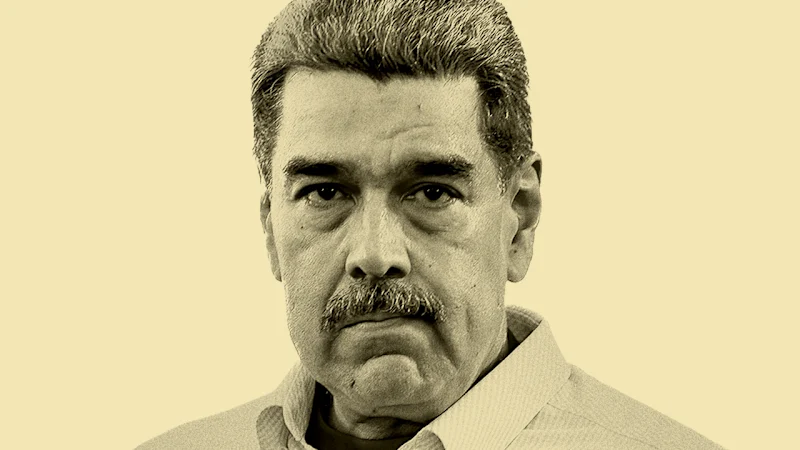

The Chavez government did improve living conditions by spending oil revenue on healthcare and education, building homes and delivering welfare to some 200,000 families in what Chavez called a Bolivarian Revolution (his populist ideology was known as “Chavismo”). Structurally, though, the economy had yet to recover from Black Friday. “Corruption and mismanagement persisted, even worsened,” says Sanchez-Urribarri. “It’s actually one of the main reasons the Chavista project didn’t work – rampant corruption, lack of accountability and utter mismanagement killed it.” Chavez nationalised more than 1000 firms and vast swathes of agricultural land, which discouraged foreign investors (who feared their assets would be nationalised too) and prompted farmers to warn of impending food shortages. He sacked thousands of supposedly disloyal staff at the state-run oil company PDVSA (Petroleos de Venezuela, SA), resulting in loss of skills, decaying infrastructure and a catastrophic decline in output that reverberates today. In 2023, Venezuela exported around $US4 billion ($5.8 billion then) of crude oil, a drop in the ocean compared to Saudi Arabia’s $US181 billion, and barely a fifth of the robust production of the pre-Chavez years. Symbolic of Venezuela’s misfortunes, work on the country’s third-tallest building, the Centro Financiero Confinanzas, known as the Tower of David, began in 1990 but stalled due to financial shocks. Lacking lifts, glazing and even walls, it famously became a post-apocalyptic vertical slum for hundreds of homeless families who ingeniously supplied themselves with water and power until they were eventually evicted and rehoused by the government (it remains incomplete). In this precarious economy, hyperinflation was a constant threat. Crime, drugs and poverty replaced glamour and cocktails. There was outrage when a former Miss Venezuela, soap-opera star Monica Spear, and her British ex-husband were shot dead in a roadside robbery after their car broke down, her five-year-old daughter surviving a bullet in the leg. ‘The country’s democratic decay has been death by a thousand cuts.’Raul Sanchez-Urribarri, La Trobe University Chavez died from cancer in March 2013. He had made it clear that he expected his successor to be his vice president, Nicolas Maduro, a former bus driver and union leader. The following month, Maduro was elected president. Not as charismatic as Chavez but a tenacious operator, Maduro has kept his grip on power by feting the military, silencing dissidents, controlling the media and judiciary, and playing fast and loose with election results, most recently in 2024. “The country’s democratic decay has been death by a thousand cuts,” says Sanchez-Urribarri, who co-edited a new book detailing the process, Authoritarian Consolidation in Times of Crisis. Some 2000 political opponents are in jail, according to the Venezuelan human rights group Foro Penal. Maduro’s regime simply banned the opposition leader Maria Corina Machado from entering elections, and when her stand-in candidate, Edmundo Gonzalez, apparently swept to victory in last year’s poll, Maduro had himself declared the winner by the Supreme Court. “We haven’t seen the full published outcome of the election,” says Angosto-Ferrandez. “The National Electoral Committee has not released full results, despite the Supreme Court supporting those results. So yes, the controversy is there.” Machado, who won this year’s Nobel Peace Prize for her “tireless fight for peace in Venezuela and the world” is in hiding in Venezuela; Gonzalez is in exile in Spain. Maduro clings on despite the fallout of serious economic sanctions from the United States, says Rodrigo Acuna, a Sydney-based commentator on Venezuela’s foreign policy. “He’s proven himself to be quite skilful and managed to hold on to power.” The bolivar was worth so little it was cheaper to use it as toilet paper than to buy the real thing. His regime, known for jailing economists who publicise unwelcome inflation data, has blamed much of its economic woe on US sanctions, which have been employed by a succession of US governments since 2005 “on Venezuelan individuals and entities that have engaged in criminal, antidemocratic or corrupt actions”, according to Congress. Targets include human trafficking, not co-operating adequately with anti-terrorism efforts, corruption, human rights abuses and government repression. Early sanctions, imposed by the Bush and Obama administrations, were largely aimed at a handful of highly placed individuals. From 2017, Trump began to escalate these measures, including sanctions against the state-owned oil producer PdVSA in 2019. By August 2018, the bolivar was worth so little it was cheaper to use it as toilet paper than to buy the real thing. Nine out of 10 Venezuelans surveyed did not earn enough money to feed themselves properly. In the past decade, some 8 million people (of a population of about 28 million) have fled the country. The good news is that inflation is down – in April, to 172 per cent. Other Venezuelans spurred by poverty have turned to illegally mining gold, despoiling parts of what was once pristine wilderness and polluting waterways with poisonous mercury. Caracas still regularly tops the lists of worst cities for crime, currently competing with Pietermaritzburg and Pretoria in South Africa and Port Moresby in PNG, according to the statistics aggregator Numbeo. While official homicide rates have fallen since a peak in 2016 – possibly because of government crackdowns on gangs – armed robbery, kidnapping, drive-by shootings and carjackings remain relatively common, as are fake taxi drivers at the airport who kidnap unwitting travellers (Concorde’s VIP service now a distant memory). What might be motivating Trump in Venezuela? Few analysts believe that Trump’s actions in the Caribbean are really about stopping the drug trade from Venezuela. His target has always, at least ostensibly, been fentanyl and its relatives, the synthetic opioids responsible for more than 70,000 overdose deaths in the United States every year. It was over the fentanyl trade that Trump imposed, or threatened to impose, sanctions on immediate neighbours Mexico and Canada early in this term. Yet Venezuela is not known to be a major manufacturer or exporter of the drug, which is more commonly made in Mexican border towns using China-sourced ingredients. “I don’t think the drugs are the issue,” says Acuna. “According to most respected international experts, including the United Nations, the majority of fentanyl is coming from Mexico and cocaine is still coming from Colombia. So Venezuela plays a very small gateway [role] regarding narcotics into the United States. It’s more an actual transit point, it’s not anywhere near an actual producer of any of those two drugs, which are the main drugs consumed inside the United States.” The White House is nevertheless adamant that it is waging a war on drugs, that the drug runners are akin to terrorists and that the US has the right to fire upon them in international waters – a claim widely disputed by legal experts. The Trump administration has characterised the cartels smuggling drugs as “non-state armed groups” whose actions “constitute an armed attack against the United States” and has claimed that the Venezuelan Tren de Aragua prison gang had sent operatives into the US to commit crimes, a form of “irregular warfare” conducted under the orders of the Maduro government. ‘I’m not going to necessarily ask for a declaration of war. I think we’re just going to kill people that are bringing drugs into our country.’US President Donald Trump Trump refused to recognise the Maduro regime in his first term and now describes Maduro as a “narco-terrorist” connected to the drug cartels. In mid-October, he took the unusual step of publicly confirming he had authorised CIA covert operations inside Venezuela. In late October, after two US bombers flew near Venezuela’s coastline, he threatened: “There will be land action in Venezuela soon. I’m not going to necessarily ask for a declaration of war … I think we’re just going to kill people that are bringing drugs into our country. OK? We’re going to kill them. You know, they’re going to be, like, dead.” Some analysts suggest he wants to topple the Maduro regime, long a thorn in the side of the United States, by deploying a show of force that might spur an opposition uprising or somehow persuade Maduro to step down peacefully. Or, as the Miami Herald has suggested, by cutting off drug revenue to corrupt senior military and police commanders in order to undermine their support for Maduro. Other options being weighed by Trump, according to a New York Times report citing unnamed US officials, include sending in special operations teams to capture or kill Maduro and having counter-terrorist forces seize airfields and oil infrastructure. Issues closer to home might also be in play. Domestically, suggests Angosto-Ferrandez, “It’s very convenient for Trump and his propaganda to have this sort of rival, using this neighbour, a weaker country in the neighbourhood, as a target.” Acuna suggests much of this may well be driven by Trump’s Secretary of State and interim national security adviser, Marco Rubio, a Cuban-American from Florida with ties to Cuban and South American exiles in the US who hate the socialist governments of their near-neighbours. “Marco Rubio does come from that hard right that in Florida absolutely despises the Cuban government,” he says. “They would view it [as] much more important to get rid of Venezuela because of its oil dollars than Cuba … Venezuela has become the main rebel state of the region.” (Cuba has long relied on its close ally Venezuela for oil but is now having to turn to Russia and Mexico for intermittent supplies.) There is also a theory that action, or at least posturing, against Venezuela is a warning to China, Venezuela’s biggest creditor and importer of its crude oil, and whose influence in the region Trump has already challenged over Chinese-linked ownership of port facilities in the Panama Canal. Also in the mix, according to The New York Times, is that should Maduro fall and be replaced by a stable leadership, the Trump administration believes an oil boom could ensue. Trump cancelled US energy company Chevron’s licence for Venezuela earlier this year, then renewed it with conditions that would stop any “hard currency” reaching Maduro. “It is a topic that fascinates Mr Trump,” reports the Times, citing unnamed officials. Acuna points to US activity in Venezuela that has waxed and waned from accommodation (to support US companies) to pressuring for regime change since the early 2000s. “This situation needs to be looked at in a broader historical context, where the United States has been aiming to overthrow, get rid of, engage in regime change with the government of Venezuela.” For his part, Maduro has reportedly made attempts to cool the current situation. In September, after the first strike on a boat, he wrote a letter to Trump, seen by Reuters and confirmed by sources to CNN, rejecting claims that Venezuela was a major hub for Colombian drugs and saying he would send the US “compelling data” to show that drugs are not trafficked or produced there. He implored Trump: “I hope that together we can defeat the falsehoods that have sullied our relationship, which must be historic and peaceful.” Reuters reported there had been no immediate response from the White House. “Maduro is clearly making overtures,” Geoff Ramsey, senior fellow at the Atlantic Council think tank, told the news organisation. “The question for the White House is, how do they get a victory here? Maduro is not going to want to deliver his head on the silver platter to the Venezuelan opposition or to the Americans.” Why does this sound vaguely familiar? The United States has meddled in regime change in South and Central America since it established the Monroe Doctrine in 1823 to warn off other nations from colonial ventures in its neighbourhood. In the latter half of the 20th century, as this doctrine morphed into the domino theory of Cold War anti-communism, the US propped up a parade of appalling dictators, such as Chile’s Augusto Pinochet and Haiti’s Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier, to counter socialist or communist elements that had popular support. Their efforts were often unsuccessful, most famously in the botched attempt in 1961 to overthrow Castro’s communist Cuban regime by landing anti-communist exiles on a cove known as the Bay of Pigs; they were roundly defeated in two days. From 1982, the US Central Intelligence Agency provided weapons and other support to the rebel group known as the Contras in Nicaragua to topple the socialist-influenced Sandinista government, an effort that largely failed but did untold damage to the local economy (a story told entertainingly in the Tom Cruise vehicle Made in America). The US invasion of Panama, in 1989, was more effective, at least from an American point of view, securing the Panama Canal and leading to the capture of pock-faced dictator Manuel Noriega, who was tried in the US for drug trafficking and imprisoned (the incursion, mostly by US troops already based in Panama, also wrecked the economy and killed several hundred, or more, Panamanians). ‘The Venezuelans have got enough weaponry to provide some level of resistance, at least for a few days or a few weeks.’Rodrigo Acuna Some see the Panama campaign as the model for a similar venture into Venezuela, especially given Trump’s claims that Maduro is implicated in drug cartels. Note, though, that in Panama the Bush administration could claim an element of self-defence, after Noriega declared a “state of war” with the United States and an off-duty US Marine was shot dead by Panamanian soldiers. No such provocation has yet occurred in Venezuela; indeed, Maduro has reportedly reached out to Trump in an attempt to end the hostilities. Noriega, meanwhile, posed little threat to US forces, of which there were more than 20,000, but which still took casualties: 23 killed and more than 300 wounded. Venezuela, ultimately, would be a soft target for the US military but it is positioned to fight an asymmetrical war of resistance, deploying guerillas alongside regular forces, a handful of reasonably modern aircraft, a small navy and numerous portable anti-aircraft defence systems. “The Venezuelans have Russian fighter jets, they have a lot of surface-to-air missiles,” says Acuna. “So they’ve got enough weaponry to provide some level of resistance, at least for a few days or a few weeks. And that’s going to come at a cost to the United States. If this does result in a full-scale US military intervention, I don’t think it will be a walk in the park. I think there will at least initially be some strong resistance. And I think if they are able to overthrow Maduro, I do think what’s going to occur in Venezuela is that a very harsh military regime will be put in place.”