Copyright New York Magazine

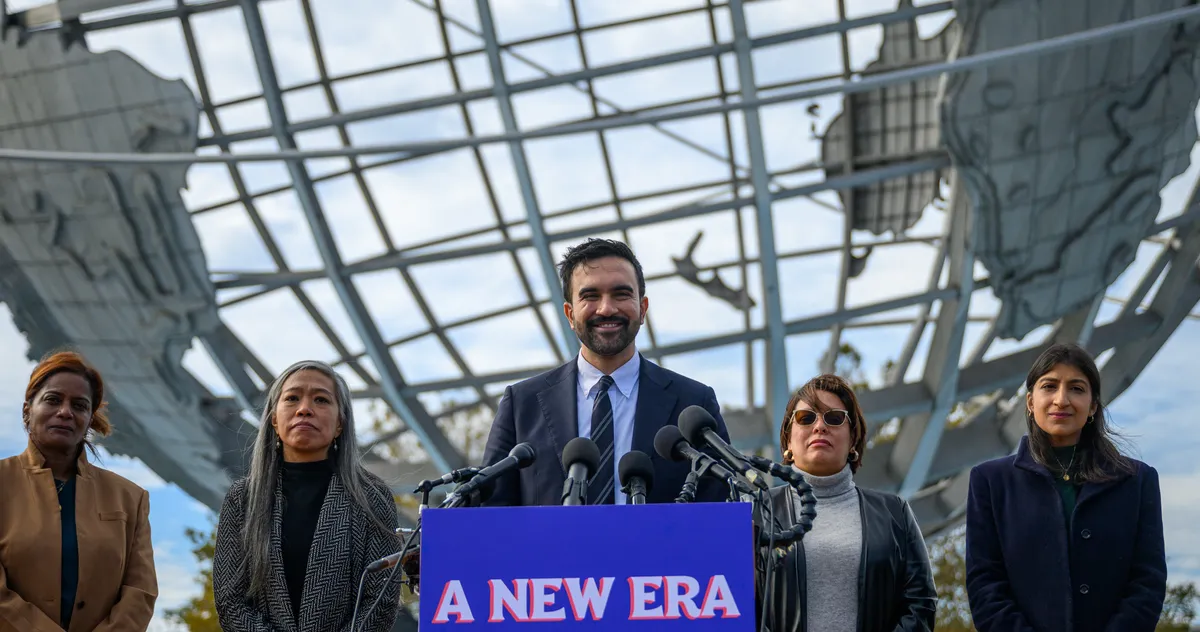

Certainly [Mamdani’s] a different stripe of outsider than the genteel reformers who emerged at the end of the nineteenth century, or the Progressives who came after them. Before the First World War, socialist candidates for mayor appeared on ballots in more than half a dozen elections, though most struggled to find support outside the German- and Jewish-immigrant neighborhoods of the Lower East Side. (Henry George, a socialist-backed land-tax reformer, was among the most successful, coming in second in 1886, ahead of the Republican candidate, a young reformer named Theodore Roosevelt.) Yet Steffens wrote with a warning to those who put their faith in any single election to deliver lasting change. “Any people is capable of rising in wrath to overthrow bad rulers,” he wrote. “New York has done it several times. With fresh and present outrages to avenge, particular villains to punish, and the mob sense of common anger to excite, it is an emotional gratification to go out with the crowd and ‘smash something.’ ” The machine was durable—it adapted itself, and was always ready to rev back up when the outsiders inevitably stumbled. Steffens wondered if it was really possible for any individual leader to break this pattern. In the early twentieth century, reformers in cities such as Chicago and Detroit were so disillusioned by the failures of their city governments that they talked about stripping mayors of their powers. But New York City wanted, and still wants, for its mayors to be quite powerful. No other elected official in the country so completely embodies the urban experience as the mayor of New York, and no other is so empowered to change the nature of city life. This power has made heroes of some mayors but turned others into buffoons and heels. Certain hurdles are inevitable: police scandals and debates about crime and policing have defined mayoralties for more than a century. Mayors have tangled with governors and Presidents, sometimes disastrously. Private interests in real estate and business have been willing to criticize and undermine a mayor’s position even while profiting from his policies. And the people, as Steffens knew, are fickle. Just ask de Blasio. As contested as the definition of socialism remains, Mamdani offered up a version of it New York’s voters clearly liked. Free buses, free childcare, higher taxes on the wealthy and corporations — the critical test now of course, as we are being reminded hourly by those who hope he fails — will be whether he can actually deliver on these things and more. Fortunately, Mamdani’s campaign has also given us some reason to suspect, beyond his bright and blazing charisma, that he might have the makings of a hard-nosed administrator. Threading the needle on policing, meetings with the business community, taking in new ideas on housing, all while retaining the support and enthusiasm of a progressive base — all this was a preview of the balancing act Mamdani will have to do if he wants to succeed where recent progressive mayors and a long line of frustrated New York City reformers haven’t. Whatever he manages to accomplish as mayor, much of potentially national significance can be learned from his candidacy alone. Mamdani is the first New York mayoral candidate in more than half a century to have earned a million votes. It is true that he did so in a diverse and heavily Democratic city that looks nothing like America at large. But the very same can be said about cities like Philadelphia, Milwaukee, and Detroit — among the swing state urban areas where maximizing Democratic turnout and vote share is critical to winning both state races and the Electoral College. Last year, Donald Trump made gains in all three on his way to very narrowly winning Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Michigan and the presidency — thanks in large part to increases in support from working class minorities and young men. Both are constituencies where Mamdani rapidly and remarkably built strength over the course of the year — beating Cuomo by nearly 40 points with men under 30 and by double digits in some minority neighborhoods Cuomo had initially won during the primary. In part, that’s because the media, still New York-centric, even in this supposedly decentralized age, tends to hype New York mayoral politics beyond its real significance. And it’s also because the office of mayor of New York City has tended to be a political springboard to nowhere. Time and again, we’ve seen famous New York City mayors, from John Lindsay to Rudy Giuliani to Michael Bloomberg, hyped as national political influencers, only to flop outside the five boroughs. When Eric Adams was elected just four years ago, there was a lot of talk about how his distinctive branding as a tough-on-crime African American moderate might make him a leader for the national Democratic Party. Obviously, that didn’t work out, and all of those figures were at least trying to be centrist or moderates. Whereas Mamdani has been elected as the left-wing mayor of a left-wing city, and imagining that makes him a model for how the Democratic Party should compete nationwide is a little bit like imagining that a far-right Republican elected in Alabama or Idaho is likely to offer a template for how Republicans should compete in swing states. That’s likely to be a fantasy. The New York electorate is not like a purple House district in Pennsylvania or Wisconsin, but a victory here is like winning one of America’s largest states. More than 1 million Democrats voted in the primary that nominated Mamdani, and more than 2 million flocked to the polls in the general election, the most in more than 50 years. Mamdani proved that a leftist who relentlessly focused on affordability concerns can win over hundreds of thousands of people, especially the young. It helped that he was uniquely charismatic and adept at social media, his posting on Instagram and TikTok making him an immediate microcelebrity in the short months before he morphed into a genuine one, but Mamdani’s rise was about more than a slick online presence, just as Obama’s 2008 victory could not be explained simply by a younger candidate’s campaign mastering Facebook. An anti-Establishment current is pulsing through America, and it was Mamdani, in New York, who was able to tap it and speak to the frustrations of a public that is weary of the many aging leaders who have refused to release their vice grip on power. Much of the content about Mamdani online isn’t just coming from his campaign or the dozens of political influencers invited to cover it. It has come from his fans. For the past few months, feeds have been filled with fancams, fan art, and videos created not just with Mamdani but for him. This form of participatory online fandom has traditionally been reserved for celebrities and musicians like Taylor Swift or K-pop idols. The young voters who came out in support of Mamdani in droves this week grew up engaging with their favs online in these ways, establishing something incredibly rare for the 34-year-old mayor-elect—a fandom. “They are using their experiences from online fandom to do politics,” says Ashley Hinck, an associate professor at Xavier University who teaches digital media and online communication. “Those are the skills to engage with culture and that means those are the skills we use to engage with politics.” … This fandom doesn’t look like average political organizing. Online, clips of Mamdani speaking at rallies and with influencers get remixed into tight video posts set to Jay-Z’s “Empire State of Mind,” songs from the Broadway musical Hamilton” or Charli xcx’s Brat. Digital artists have posted videos of them drawing Mamdani in their own styles. Mamdani’s own campaign quips, like when he instructed opponent Andrew Cuomo on how to pronounce his last name, have been edited into campaign anthems. Both Trump and his administration are less interested in helping ordinary Americans than they are in fulfilling their idiosyncratic program of austerity, pain and deprivation. They are all stick, no carrot. It’s against this backdrop that voters just went to the polls and cast millions of votes against the president by way of Democratic candidates, moderate and progressive, who stood for both affordability and the nation’s most cherished values, who pledged to use their time in office to protect their new constituents from the provocations and assaults coming from the government in Washington. If these elections had gone the other way — if the Democratic Party had underperformed or even lost one of these contests — then every commentator under the sun would say, rightfully, that Democrats were in disarray; that even the president’s deep unpopularity couldn’t keep them afloat with voters. But Tuesday was a Democratic victory. And the party didn’t just win — it won by commanding majorities on virtually every field of play. In polls, in focus groups and now at the ballot box, the public is telling us something very clearly: Trump is simply too much. If this is an opportunity for Democrats to win back lost ground — and it is — then it is also a warning to a Republican Party that has tied its entire identity to the man from Mar-a-Lago. Set aside the endless and sometimes annoyingly abstract debate over whether the Democrats should move to the left or to the center, and a pair of insights emerge from Tuesday’s results, both of which might give some hope to a Party that has lately been starved for it. First, the prospect that the 2024 election marked an electoral “realignment,” in which young and nonwhite voters without college degrees moved inexorably toward the Republicans, now seems increasingly unlikely. The margins in Virginia, where Spanberger won by about fifteen percentage points, and New Jersey, where Sherrill won by twelve, suggested that these weaknesses had been largely circumstantial, with some racially diverse areas that had been drifting away from the Democrats, such as Hudson County, in New Jersey, swinging back toward them on Thursday. In the Washington Post/ABC News poll taken shortly before the election, sixty-six per cent of young voters disapproved of the job that President Trump is doing, as did more than seventy per cent of racial minorities. (“That’s not screaming realignment,” the analyst Ronald Brownstein noted.) Exit polls published by NBC had Spanberger and Sherrill winning men under twenty-nine—the demographic most thought to be fleeing to the right—by ten points. Mamdani won them by forty. This time, it was the New York socialist who brought new voters into the political process. Maybe more significant, as Mamdani, Sherrill, and Spanberger all seemed to recognize, Trump has handed them not just an issue but a theme that the Party might carry through to the midterms. Having won the Presidency in part because of concerns about the escalating cost of living, Trump has governed in ways that have deepened the problem. His so-called One Big Beautiful Bill Act amounted to a vast transfer of money from the poor to the rich. He has been personally fixated on an escalation of tariffs that has made ordinary goods much more expensive. During the ongoing government shutdown, he has at one point refused a court order requiring his Administration to disburse funds to pay food-stamp recipients, as lines at food pantries grow. Millions of people now stand to lose health insurance because of the President’s hard-line position in budget negotiations. The most natural campaign for Democrats to run—one that the Party was built to run in the twentieth century—is ordinary people against the rich. Trump is handing it back to them. Cue the ads: the billionaire pardoned after investing in the Trump family’s crypto projects; the twenty billion dollars sent away to bolster the Argentinean President, a political ally of the White House, at the expense of American farmers; the bulldozers razing the East Wing in a project underwritten by Trump’s donors. [W]hat we’ve seen in our most recent survey in September was Democrats are very frustrated with their own party. Two-thirds of Democrats that we interviewed said they felt frustrated by the Democratic Party. I think that’s pretty consistent with some of the voter surveys in New Jersey and Virginia we saw this week that showed Democratic voters may be frustrated with their own party, but they’re still motivated to come out and vote against Republicans. Democrats now are more frustrated than Republicans were with their party four years ago. Democrats today are angrier with the Democratic Party than Republicans were four years ago. Democrats today, in our polling, are less hopeful about the Democratic Party than Republicans were about their party four years ago. After losing the 2020 election and after Jan. 6, Republicans were still more likely to say they were hopeful about the Republican Party than Democrats were hopeful about the Democratic Party. These polls were conducted before the elections this week, but I think there’s a sort of disconnect between how Democrats feel about the Democratic Party and how Democrats feel about voting in these elections. I think that that chasm was on display in these states. The Democratic candidates who won on Tuesday span a pretty wide spectrum, by basically every measure, including ideology. And when you look at this Democratic frustration, it’s pretty across the board, in our polling. Democrats who identified as liberal were a little bit more likely to say that they were frustrated with their party than Democrats who identified as moderate or conservative. This just means that this battle is going to play out in primaries throughout the country in the next two and a half years, culminating with the presidential primary in 2028. I want to be very high-minded about this. Nothing good comes from a race to the partisan bottom, with red and blue states alike redistricting whenever they want. But I also look back on four years of the Biden administration and realize that, even after four years of Donald Trump, Democrats utterly failed to put safeguards in place to prevent a faster and furious-er sequel. Now we’re out of good options. Our democracy is on life support. And Newsom, at least, is attempting via democratic means to keep Trump from pulling the plug. Does that make him presidential material? I’m not sure you’ll ever see me with a “Newsom 2028” button. But the man knows how to stand strong, and like many men who read to me as narcissists, he certainly knows how to grab attention. As liberal commentator Chris Hayes has written about at length, attention is the world’s most endangered—and possibly most valuable—resource. Trump knows how to grab it. So does Newsom. Among the constituencies that swung the hardest toward Democrats [on Tuesday] were Latinos, who helped power Trump’s presidential win last year and were key to the GOP’s redrawn congressional map in Texas. The Republicans’ chances of flipping five additional House seats there rest in part on their holding Trump’s gains among Latino voters. That was a questionable assumption from the start, the longtime GOP strategist Mike Madrid told me. It appears even shakier in light of Tuesday’s election results; in New Jersey, for example, the state’s three most heavily Latino counties moved sharply back to the left after swinging toward Trump in 2024. “None of this is good for Republicans. It’s all their own doing, though,” Madrid said. Latinos in Texas border towns may vote differently in 2026 than Latinos in New Jersey did this year. But the anti-GOP shift in this week’s elections could boost the Democrats’ chances of winning two and possibly three of the five Texas seats that Republicans redrew in their favor, Madrid told me. It could also open up even more opportunities for Democrats, because to create the additional red-leaning seats, Republicans had to cut into previously safe GOP districts. “The problem is they’re spreading their other districts thin as they’re getting greedy,” Madrid said. Yesterday’s election results could complicate both parties’ plans to escalate their gerrymandering tit-for-tat across the country. In addition to their Texas effort, Republicans have enacted newly drawn congressional maps in Missouri and North Carolina that could yield them an additional House seat in each state. Florida legislators are eyeing a gerrymander that could boost the GOP’s chances in multiple seats, although the state’s significant proportion of Latino voters could pose similar redistricting challenges for Republicans there as those in Texas saw. It was classic Trump dominance theater, like many other occasions this year where he successfully muscled recalcitrant Republicans to confirm controversial nominees, support divisive policies and enact sweeping domestic policy legislation. But upon returning to the Capitol, the senators made it very clear: They planned to blow Trump off. One GOP senator, Mike Rounds of South Dakota, laughed out loud when asked about the anti-filibuster push. Welcome to the dawn of Trump’s lame duck era. Don’t expect an immediate stampede away from the president, according to interviews with GOP lawmakers and aides Wednesday — he remains overwhelmingly popular with GOP voters and is the party’s most dominant leader in a generation. Trump’s top political aide signaled Monday that the White House is not worried about a messy “family conversation” about the filibuster. But with Tuesday’s stunning election losses crystallizing the risks to downballot Republicans in 2026 and beyond, there are growing signs that lawmakers are contending with the facts of their political lives: He’ll be gone in just over three years, while they’ll still be around. The danger for the president is that if Trump can’t run roughshod over the thin GOP congressional majorities, it would leave him few legislative options given his scant interest in compromising with Democrats.