Copyright independent

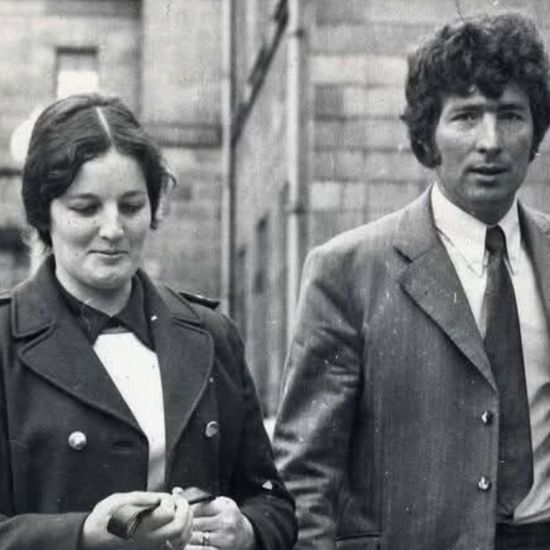

Her family remember her as a -loving mother and -grandmother with a wicked sense of humour who never sought credit for the role she played in breaking the Catholic Church’s grip on the sexual health of generations of Irish women. Mary Grimes was born in 1944 in Skerries, north Co Dublin, as one of seven children. She was deaf from an early age but learned to lip read. She was 14 when she met Shay McGee, who lived near Rush. Like his father, William, a merchant seaman decorated for his role in World War II, Shay had followed the call of the sea. He had left school at 13 and took up fishing from Skerries. The couple married in June 1968 and initially lived in a caravan in Loughshinny. They had four children between 1968 and 1970, but McGee developed complications after each birth and was in a coma for three days after her twins were born. The couple’s GP, Dr James -Loughran, warned her she would risk a stroke that could prove fatal if she had a further pregnancy. Her condition meant she could not use hormonal contraception. Dr Loughran advised her to use a diaphragm. However, May could not legally import the spermicide jelly used with the diaphragm because the Criminal Law Amendment Act (1935) banned the importation of contraceptives. When her mail -order arrived from England, it was confiscated by the Customs Service. She was warned that she and her husband would face prosecution if she tried again. Dr Loughran was one of the founders of the Irish -Family -Planning Association, and he -encouraged the couple to take a case against the State on the grounds that the ban was unconstitutional. Their case was dismissed by the High Court in 1972, but was -appealed to the Supreme Court. The McGees were represented by Donal Barrington and future -president Mary Robinson, then a young barrister who had, as a -senator, pioneered attempts to change -anti-contraception laws. At one point Shay stopped the hearing during cross--examination to say he would “prefer to see May using contraceptives than be -placing flowers on her grave”. The Supreme Court found 4-1 in McGee’s favour, stating the couple had a broad right to marital privacy. In an interview with Ruadhán Mac Cormaic for his book The -Supreme Court, McGee said that she found the Four Courts “cold and scary… an awful place to be”. The ruling was recognised as -paving the way for legalisation of contraceptives. However, Mac --Cormaic noted it was also the -catalyst for a conservative -political campaign that led to the 1983 amendment to enshrine the right to life of the unborn in the constitution. The week of the Supreme Court ruling, the McGee family were at mass in Skerries with their young children, including their eldest son Martin. Then five years old, he -remembers how his father told the family they were leaving the church after the priest said there were people present who were not welcome. McGee’s mother, known as -Granny Grimes, was a devout Catholic, but was not fazed by critics. “Ah, f**k them,” she told her daughter. The couple received congratulatory letters from individuals and bodies such as the World Health Organisation, and an envelope with money from a Northern Irish -clergyman, but they also got more hostile correspondence. May -returned the clergyman his money, but the couple did accept a payment from a British tabloid newspaper for an interview. It allowed them to put a IR£750 deposit on a house in -Skerries, and they also bought a black-and-white television. The couple had two more children, Darren and Andrea. Their father then had a vasectomy in 1981. As Martin recalls, his parents never talked about the case and it was only after they found a folder with some press cuttings that the family began to ask questions. “It wasn’t that they kept it from us, but my mother was just very humble,” Martin said. “She was very determined. She told us she would have gone to Europe with the case if it had been turned down by the -Supreme Court.” In December 2023, Mr Justice Gerard Hogan presented her with the Praeses Elit award for advancing societal and legal discourse at a conference in Trinity College, Dublin marking the 50th anniversary of the case. Mr Justice Hogan said the case was “the legal equivalent of a moon landing”, which “started a social revolution”. TCD Law Society auditor Eoin Ryan described May as “a trailblazer” and said that “as young people we owe her and her husband Seamus McGee the world of gratitude for changing the face of Irish society and helping to usher in a new and progressive Ireland”. Heartbroken after Shay died in January last year, May decided to dye her hair purple and live life as best she could. Several months ago, she was invited to the unveiling of a mosaic by Wexford artist Helen McLean in Floraville Park, Skerries, honouring her and Shay. May was dedicated to her children and grandchildren, friends and neighbours and she “never complained”, Martin said. “She was the most positive woman I’ve ever known.” Mary ‘May’ McGee is survived by her children Martin, Gerard, Sylvia, Sharon, Darren and Andrea, and 13 grandchildren.