Copyright Newsweek

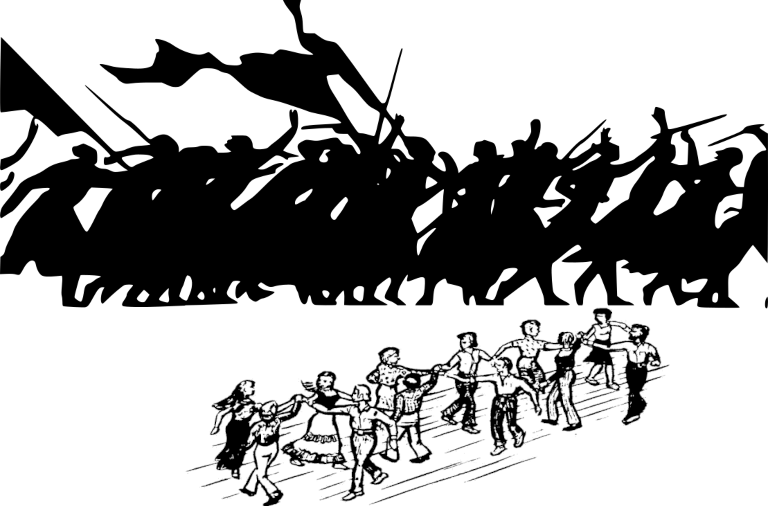

In the final stretch of New York City’s mayoral race, the attacks against Zohran Mamdani have crossed a line—not just politically, but morally. What began as disagreement over policy has hardened into something older, more familiar and more dangerous: the suggestion that a Muslim cannot be trusted to lead the most diverse city in the United States. The rhetoric has not been subtle. Former governor Andrew Cuomo recently laughed and agreed when a radio host suggested Mamdani would cheer another 9/11. Mayor Eric Adams warned that New York “cannot afford to become Europe"—language that has long functioned as political shorthand for demographic anxiety. Cuomo and Curtis Sliwa claimed during a televised debate that Mamdani supports “global jihad.” Political action committees have circulated push polls falsely suggesting Mamdani intends to make halal mandatory, and attack ads have darkened and elongated his beard to evoke the visual coding of menace. Conservative commentator Larry Elder circulated a cartoon depicting a plane labeled “Mamdani” flying toward the New York skyline—an unmistakable reference to 9/11. Even the way Mamdani eats has been mocked. None of these tactics are spontaneous. They reflect a deliberate reactivation of suspicion. One of the most frequently repeated attacks centers on a photograph of Mamdani standing beside Imam Siraj Wahhaj—a respected Brooklyn faith leader. The imam has met publicly with Michael Bloomberg, Bill de Blasio and Eric Adams with little controversy. Only when Mamdani appeared with him did opponents resurrect insinuations tying the imam to the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. Yet Andrew C. McCarthy, the lead federal prosecutor in that case, has stated unequivocally that it is “inaccurate” to claim he'd ever alleged Wahhaj was a coconspirator in any terrorist plot. He was not charged. He was not named as an unindicted co-conspirator. No evidence has ever tied him to the attack. In fact his evidence helped the goverment case in the end. The smear persists not because it is true, but because it is useful—a reminder of what Mamdani’s identity is assumed to mean. Paradoxically, Israel has become a defining wedge issue in this local election. Mamdani has criticized the Israeli government’s treatment of Palestinians and expressed solidarity with civilians caught in violence. Yet we do not accuse politicians of anti-Muslim hatred when they criticize the governments of Saudi Arabia or Iran. We understand that criticizing a state is not the same as condemning a people. But when the speaker is Muslim, and the state is Israel, the line is redrawn. That shift—from policy disagreement to accusations of disloyalty—is not accidental. It is the quiet architecture of Islamophobia. During the debates, Mamdani addressed these anxieties directly and without defensiveness. "I have never, not once, spoken in support of global jihad," he said. "That is not something that I have said, and that continues to be ascribed to me. And frankly, I think much of it has to do with the fact that I am the first Muslim candidate to be on the precipice of winning this election." He also reaffirmed his belief in human rights for all. He did not minimize Jewish fear, nor deny the reality of antisemitism. He rejected the political weaponization of fear. When the attacks intensified, Mamdani did something rare in contemporary politics: he did not speak to his accusers, but to those who have lived under this shadow. He addressed the Muslims of New York—the subway rider who adjusts a scarf to avoid confrontation, the traveler pulled aside “randomly” every time, the student who learns early how a name can change a room. He remembered his aunt who stopped taking the subway after 9/11 because she no longer felt safe wearing hijab. “To be Muslim in New York is to expect indignity,” he said. “But indignity does not make us distinct. It is the tolerance of that indignity that does.” That moment reframed the race. The question is no longer whether a Muslim can run for mayor. It is whether a Muslim must apologize to do so. Despite the barrage, Mamdani continues to lead among renters, young voters, working families and those concerned with transit costs, wages, child care and public safety that does not rely on racialized policing. New Yorkers are responding to the mayoral race not with panic, but with the practical concerns of daily life. They are choosing rent over resentment, subways over scapegoating, belonging over fear. The response to Mamdani's speech from U.S. Vice President J.D. Vance was telling. He responded on X by mocking Mamdani’s recollection of his aunt avoiding the subway after 9/11, writing: “According to Zohran, the real victim of 9/11 was his auntie who got some (allegedly) bad looks.” But Mamdani did not deny the horror of 9/11 or the suffering of the 3,000 people who were killed. He was naming another layer of trauma that unfolded alongside it: the surveillance, the detentions, interrogations, suspicion and quiet humiliations that Muslims endured in its aftermath. Two things can be real at once—the grief of those whose loved ones were taken, and the fear and stigmatization that reshaped daily life for an entire community. Mocking someone’s pain does not honor the tragedy; it distorts it into a weapon. Coming from a national leader, that distortion is not only dismissive—it is dangerous. The backlash reveals something deeper. The panic around Mamdani is not rooted in his policy positions, which are shared by many mainstream progressives, but in his possibility. If a Muslim tenant organizer who rides the subway and speaks openly about Palestinian human rights can be the mayor of New York, then the political story America has told itself since 9/11—about who belongs and who must prove belonging—begins to shift. If Mamdani wins, it will not be because he ignored bigotry. It will be because he refused to bow to it. It will signal that suspicion can no longer stand in for argument. It will signal that supporting Palestinian humanity cannot automatically be coded as hate. And it will signal that Muslims do not need to soften themselves to be accepted in public life. This election is not simply about choosing a mayor. It is about choosing the terms of American belonging. If New Yorkers choose Mamdani, they will not simply be choosing a candidate. They will be choosing a country where dignity is not conditional. Faisal Kutty is a Toronto-based lawyer, law professor, and frequent contributor to The Toronto Star. The views expressed in this article are the writer's own.