Copyright Resilience

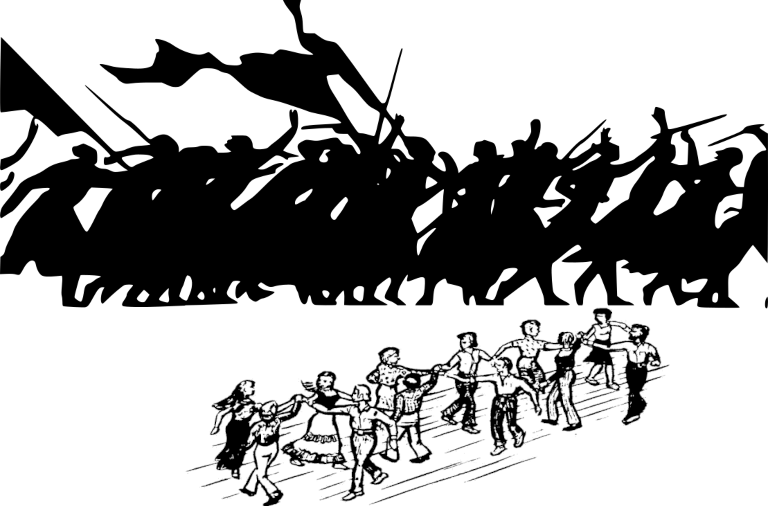

A contribution to the ecosocialism vs horizontalism debate. In the series Prospects for Degrowth A debate is in progress between alternative strategy prescriptions for degrowth. On the one side, what we might call minima-maxima or degrowth as under-labourer in a democratic socialist transformation. ‘Minima’ because it realistically notes that degrowth (whether it is a movement or not) “does not have the capacity to achieve power and implement policies“; ‘maxima’ because it aims for nothing less than transformation through a wider socialist project of seizing state power. In this, the degrowth movement would be a kind of ‘under-labourer’, beavering away to have a catalytic influence on a mass socialist party, so it became both ecosocialist and anti-growth in orientation and programme. This is essentially the view advanced by Jason Hickel in a recent interview, and elements of it were advanced by ourselves in recent pieces in the Degrowth UK series Prospects for Degrowth. We say, elements, because our perspective was more nuanced and multi-level than what Hickel was able to put forward in his interview (a written piece, at greater length and reflection might have been less one-dimensional in tone than what could be captured in an interview). On the other side, there is the ‘pluriversal’ perspective, which is less prescriptive, recognises the plurality within the degrowth movement and privileges direct democracy and the transformation of everyday life. This ‘pluriversal’ approach, wherein dialogue with, membership of and influence on the labour movement are legitimate but insufficient strategies, is the view of Vincent Liegey, Anitra Nelson and Terry Leahy, in their response to Hickel. There are some similarities to this view in the responses of both Manuel Casal Lodeiro and Mark Burton to Ted Trainer’s anarchist prescription for the degrowth movement (almost the mirror image of the Hickel piece), again in Prospects for Degrowth. Like Liegey et al., we argued for a multi-level strategy, although in Mark’s case also defending a Marxist and state-oriented approach as a vital part of the package, a position then elaborated by Anna Gregoletto. However, the above summary misses some critical dimensions of the various contributions and in what follows we will address each in turn, identifying the positions outlined by the protagonists, with an attempt at a more dialectical synthesis from us. In the rest of this article we articulate a synthesis between the two positions, that we call (ana)dialectical (or simply ‘analectical)’, that will allow us to reconcile these two positions in an attempt at strategic unity1. In recognising that the current task is to organise the degrowth movement where it is currently at, our intention is two-fold. Firstly we want to move beyond what could be the danger of polarised positions: we have great respect for the work and views of both Jason Hickel and Vincent Liegey, Anitra Nelson and Terry Leahy. Secondly, we believe (like Gasparro and Vico)2 that neither of the two positions is sufficient: we can move beyond them while taking the best from both. Our analytical framework We used these headings and definitions to create our analectical synthesis. Minima-maxima Pluriversalism (Ana)dialectical synthesis Degrowth as a movement Minima-maxima Pluriversalism (Ana)dialectical synthesis Defining degrowth Minima-maxima Pluriversalism (Ana)dialectical synthesis In our core definition, we acknowledge the risk of yielding to a restricted definition of degrowth that is prevalent in the English speaking academic sphere, namely a reduction to measurable material dimensions of economic scale. As Fitzpatrick notes3 (2025) the original French definition focussed more on the rejection of economism and hence growth, not in terms of scale but as refusal – a changing the subject, or as Latouche put it, “leaving the society of consumption” 4, or “leaving the imaginary of development to reintegrate the field of the economic with the social and the political” 5. However, we believe that to deny the centrality of the problematic of material scale is to empty degrowth of real meaning and risks making it a general anti-modern, anticapitalist, anti-economic position: remember that the first use of decroissance was by Gorz (1975) in the context of discussion on the Meadows et al. Limits to Growth report6. What he said was, “And this is the heart of the problem: global equilibrium, in which no-growth – even degrowth (decroissance) – of material production constitutes a basic condition, is this equilibrium compatible with the survival of the[capitalist] system?”. So we recover those anti-economistic meanings, and for us as Marxists, opposition to commodification is central, in the ‘belt’ of associated elements that are closely linked to the core. We assert that that core definition is materialist but not economistic, since it is (orthodox) economics that reduces material factors (material flows, geophysical stocks and sinks, diverse and complex ecosystems, etc) as well as human relations and qualities, to monetary terms. That is our dialectical attempt to resolve the discrepancy between the two positions under discussion here. Capitalism Minima-maxima Pluriversalism (Ana)dialectical synthesis Theory of change, the State and democracy Three Myths on Eco-socialism Myth One: The Eco-socialist party is top-down and undemocratic This first myth has a double sided origin story. On the one hand, it comes from real disappointments coming from attempts to make significant change within existing bourgeois parties. These attempts, as good and strong willed as they could be, faced the constraints of parties that were inherently capitalist and would never offer ways to think of a world without capitalism. In this sense, democracy within bourgeois parties is inherently limited. Freedom of thought and action is constrained within the limits of the liberal-capitalist world, while a large technocratic apparatus seeks to limit as much as possible member participation to elections every four or five years. However, an eco-socialist party would most likely be an entirely different beast. It would be based on member-led democracy, unbound by the constraints of bourgeois democracy, and it would focus on empowering people and communities as one of its strategic goals.That is because the objective of an eco-socialist party is not purely electoral, rather it is to build and cohere revolutionary consciousness. Popular protagonism is the vital energy of the mass socialist party. On the other hand, the idea that an eco-socialist party would be undemocratic has a source in the anti-communist ideology that has hegemonised Northern countries since the Cold War and has only intensified since. We all carry the baggage of a history heavily shaped by long and murderous anti-communist campaigns waged by the United States and its allies. We live in the shadow not only of the Red Scare campaigns, but of the disillusionment that affected the Left after the fall of the Soviet Union. This ideological campaign has implanted an unquestioned association between socialism and authoritarianism within public debate. Yet, this view applied to today’s left is naive and entirely ignores a whole body of activist literature written by leading left organisers in which democracy is a central focus, as well as ignoring the practices of actually existing socialist movements and perpetuating US propaganda that has often harmed Southern States . In short, dismissing eco-socialism or all other forms of socialism as undemocratic has very little to do with how the left is developing at the moment. Myth Two: The Eco-socialist State would be undemocratic and despotic Liegey et al. mention the historical reality of some socialist parties, and especially once they’ve achieved power, becoming authoritarian and even repressive and dictatorial. While it is true that this belief shares some of Myth One’s ‘intellectual’ roots, being part of US imperialist propaganda, Myth Two also points to a danger that the need to maintain cohesion and a clear line in the face of internal opposition and external threats can lead to authoritarian measures, the most famous example being the Soviet Union under Stalin, and the most extreme the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia. Even in what is perhaps the best case of a socialist revolution and a government of the people in power, Cuba, (and in the face of relentless destabilisation, even terrorism, from the USA) there has been excessive bureaucratisation, and at times repression, together with a slowness to correct inevitable mistakes. Yet the answer is not the model of liberal democracy, with pro-capitalist parties competing, but probably lies in a more thoroughgoing development of democracy with greater autonomy for mass organisations from the State and the party. Freed from the profit imperative, an eco-socialist state would be best positioned to reorganise political life around well-being and popular participation. Cuba is also instructive here. Emerging as a socialist country after defeating a totalitarian dictator, it had to invent the institutions of popular power and people’s democracy: it has done this well but the result is not perfect – maybe it never can be. Further, we stress that any evaluation has to be made in the light of the fact that the country and its leadership, has been, for six and a half decades under a state of siege, due to the continuing US blockade, renewed and intensified again and again: its achievements, including those in participative democracy and environmental restoration, are extraordinary considering this. Secondly, the reliance of ecosocialism on economic planning is contested from the horizontalist perspective, even to the extent of seeing planning as despotic. Yet, any large scale coordination of economic and social activity and development requires planning. In other words, degrowth requires planning. Put simply, there is no reason why an eco-socialist society would be despotic. Myth Three: Eco-socialism privileges industrial workers Misunderstanding is widespread that the concept of ‘working class’ equals ‘industrial workers’. Following Marx, the working class is those who have to sell their labour power to live – that is all of us, including those who have a what is effectively a discretionary exemption from the labour market (children, people with severe disabilities, unpaid carers, retirement pensioners). Although the working classes might be internally divided between those who have access to higher wages and those that are extremely exploited, the definitional characteristic of the working class is one of exploitation by the ruling classes worldwide (via the expropriation of surplus value – and we’d also include those facing more overt expropriation via ‘primitive accumulation’). Industrial workers would be part of a coalition of oppressed peoples against capitalism/imperialism8. The pitfalls of The Party The minima-maxima proposal is a wager that degrowth can indeed capture or convert the majority of socialists to a degrowth-informed eco-socialist understanding and programme. It is rather a tall order, but as the systemic crisis deepens, not entirely implausible. Another problem with a purely party-based strategy is the risk of co-optation. Many attempts at party building have fallen into the electoralist trap: the sphere of politics shrinks to fighting for elections. There is also a practical problem with the minima-maxima idea. This proposition does not take into account the current state of the actually existing degrowth movement, which at the moment is unlikely to get behind the eco-socialist banner. A very large part of the degrowth movement has done a lot of research and experimentation on prefigurative strategies and attempted the creation of ‘nowtopias’. Certainly, this vision has enormous problems if left isolated by broader political projects, as we will analyse below, but we also do not want to ignore that this praxis is very important for degrowthers. Indeed, this orientation towards utopian thinking, if part of a political project and organisation, could be able to reach terrains that a strategy only focused on seizing political power would not. Strategies that focus on seizing political power through the party instrument address one aspect of the struggle against capital, but there is a broader reality of the capitalist ideology-action-structure complex that these strategies take insufficient account of.9 In this way, the capitalist system is not only sustained by the state but by this complex that, while including the state (within its structures), also goes beyond it to acknowledge the role of ideology (“socially embedded and embodied systems of thought about the way things are and how they should be”) and action (daily activities and practices of social reproduction). This means that transitioning out of capitalism requires us both to break with the existing system and also to replace it with a different way of living and reproducing ourselves. It is the critique of commodification that distinguishes reformist social democrats from revolutionary socialists, including, we would argue, eco-socialists. That is why ecosocialism is so compatible with degrowth. Unless the transformation also includes the totality of the way we live, we will be stuck with some form of capitalism and continued oppression of people and destruction of ecosystems. So while a party is a necessary and unavoidable instrument of revolution, focusing on the party alone will not be enough to carry out a full transition out of capitalism/imperialism. We will also need comrades whose focus is building the alternative institutions to substitute those of the growth-based capitalist order. Not only that, those alternative institutions will also help us to build consciousness and capacity to wage more effective struggle in the present. This is what actually existing degrowth spaces could contribute to a broader strategy that attempts to both seize political power and build an alternative world. To put this into terms perhaps more familiar within the degrowth movement, we will need the combination of all kinds of strategy, interstitial, symbiotic and ruptural10. The pitfalls of Horizontalism Liegey et al. seem to deny the need for a political carrying force for degrowth, it seems preferring instead to rely on an organic massing of influence from the degrowth pluriverse. As they say, this is a horizontalist approach. Yet, the recent experience of horizontalist movements serves as a cautionary tale for this type of political organisation. The 2010s were a decade in which these type of movements proliferated in the North. The world was shaken by Occupy, various student protests, and the rise of the climate movement as we know it today, through the Fridays for Future strikes and then with Extinction Rebellion and all the groups that spawned from it.11 These movements were the protagonists of moments of jubilant moments of protest. It is important to interrogate ourselves on why these movements were ultimately unsuccessful in generating the kind of system change they called for. We identify three main critiques of the exclusively horizontalist strategy. The problem of an identity-based ‘creativity politics’: Jodi Dean called it the ‘politics of the beautiful moment’.12 A tendency within some leftist currents to mistake aesthetics, media attention and creativity for the achievement of real political objectives. Vice versa, organisation is treated as despotic regression, rather than a tool to help us win, to organise more effectively and distribute power.13 The attraction towards this kind of tactics (too often mistaken for strategy) comes from the sad fact that identity-based ‘creativity politics’ appears more attractive and achievable “than the sustained work of party building because they affirm the dominant ideology of singularity, newness, and now.”14 Further, this kind of politics often goes in tandem with a plethora of ‘alternative lifestyle choices’ that are at risk of becoming depoliticised escapist routes for affluent people, as Eva Martínez argued in her piece on intentional communities. We cannot avoid the state: it is only possible to avoid the state to the extent the you don’t pose a serious threat to the status quo. The second a movement of any kind becomes a concrete threat to the capitalist/imperialist order, it will be subjected to relentless repression, ranging from infiltration, policing and worse.15 Further, the state would also serve as an important instrument to protect a post-capitalist world from counter-revolutionary forces and interventions. This does not mean having illusions about the nature of the State: as Marx noted, under capitalism it functions as the ‘executive committee of the ruling class’. So an adequate strategy has to both weaken and dismantle the capitalist state, using the leverage it affords for both emergency action on the ecological and climate emergency and rebuilding society, but ultimately replacing it with another form of societal coordination, which might still be called the State, but might not. The problem of disaggregation: one of the most stereotypical problems of the Left is the lack of unity and strategic or even principled cohesion. Forces that should be in coalitions are splintered in small, single-issue isolated struggles, sometimes not even knowing who is around them doing what, and often fighting each other as much as the system. Without a unifying, organisational force and structure “multiple resistances blur into the menu of choices offered up by capitalism, so many lifestyle opportunities available for individual diversion and satisfaction.”16 So, if we refuse to engage with the party (or parties) as an instrument for political coherence, degrowth will risk becoming little more than a ‘lifestyle choice’ for Northern intellectuals tired of consumerist society and craving voluntary simplicity. After examining the pitfalls of both an exclusively party-based strategy and an exclusively horizontalist vision, we move beyond this binary altogether to demonstrate that the opposition between horizontal social movements and local initiatives and political parties is ultimately a false choice. For an (Ana)dialectical Movement Ecology We seek to resolve this apparent contradiction through an (ana)dialectical approach, one that seeks (dialectically) to synthesise and transcend the two other views, while being open to the voice of those excluded from the debate. We find that Nunes’s framework on movement ecology17 is helpful to articulate our vision. We believe that we can think “about what exists in ecological terms”.18 Using an ecosystem as a metaphor to describe the landscape of revolutionary forces, Nunes notes that “a healthy ecology needs several actors that combine the ability to intervene at certain key points of the chain with the capacity to think the chain as a whole.”19 In this sense, a healthy movement ecology allows the flourishing of strategic pluralism, imagining the emergence and consolidation of a ‘prefigurative flank’ and a state-focused eco-socialist flank, while maintaining some political organisation that prevents us from falling into the ineffective and individualistic splintering that has been plaguing leftist projects for decades. In our view, working within an eco-socialist mass party and experimenting with degrowth ‘nowtopias’ would be part of the same revolutionary ecology. Jodi Dean and Kai Heron write that “experiments in farming, urban gardening, and similar such survival oriented micro-initiatives can be expanded into the repertoire of party practices, treated as opportunities for building skills and camaraderie.”20 In fact the British socialist and Labour movement did this in the period before the second World War / anti-fascist war, with its socialist clubs, socialist health insurance, cooperatives, educational institutions, cycling and gardening societies: similar cultural practices can be found in many successful social movements21. The distinction is between 1) engagement with the state and its institutions, either to reform it or replace it, and 2) building power, alternatives, prefigurative social relations, in the community (in its diversity). The one influences and informs the other, but critically, each depends on the other. That is why political parties tend to have reference groups whose interests they represent, obscurely as the pro-capitalist parties represent the interests of various sections and institutions of capital (companies, banks, individual rich people) or more transparently, as in the now fraying historical relationship between the British Labour Party, the co-operative movement and the trade unions. For the degrowth movement, the community represented is more diverse and, ideally, it could include campaigning groups on social and environmental justice, service delivery organisations such as agroecological co-ops or community energy co-ops, community associations, such as tenants and renters associations, feminist organisations, trade unions and others. The party too might not be monolithic but might actually be a cluster of parties – we can collectively hedge our bets! Further, opportunities abound for pluriversality, dissent and deliberation even within a single party. For instance, healthy, open factions provide a way for party members to build collective power around specific issues or politics, while remaining part of the unity provided by the party they belong to.22 In this way, the party provides a structured forum for different political positions to express dissent and participation in a way that is constructive and consequential. The relationship is likely to be tense at times, since multiple interests are involved, but the common factor is the pursuit of social and economic justice strictly within environmental limits, i.e. degrowth as ecosocialism, with a widening of democracy, social, economic and political. Together, these non-State institutions build alternative, ‘counter-hegemonic’ popular power, with a new de-ideologised, good sense (political consciousness is one component) that replaces the dominant ideology of capitalism, capable of effectively resisting the inevitable counter-offensive. Such an approach can avoid the twin perils of a left party that becomes authoritarian and unrepresentative, and a plethora of movements and groups that, while doing worthy things locally fail to scale to the needed transformation. There is more that can be said on this but it is essentially a reinvention of the Gramscian model of politics for the third quarter of the 21st century: (inter)national-popular, (counter) hegemonic, playing a war of position prior to the decisive taking of power. We stress, there is no such thing as ‘changing the world without taking power’, but the taking of power is a more complex process than storming the gates of government and implanting a new regime; it means stewarding the power delegated by the people, the community, using it responsibly and accountably, which means inventing new and effective forms of responsive representation and new channels of influence and counter-control – leaders will command while obeying (‘mandar obedeciendo’ as the Zapatistas put it). A lot more could be written here about the challenges of legitimacy and governability, but that is the stuff of any ethical government23. Tools for change Minima-maxima Pluriversalism (Ana)dialectical synthesis Conclusion Urgency and immediate tasks Minima-maxima Pluriversalism (Ana)dialectical synthesis We find both the minima-maxima mass political party and pluriversalist-horizontalism inadequate to the very real challenge of changing our society and economy into a degrowth one. We do see degrowth as a planned and equitable material contraction (the core) that simultaneously rebuilds a society based on the values of, as the permaculturalists put it, care for the earth, care for each other, and care for ourselves (the integral belt). However, to achieve that is no easy task and to cast it in either vertical or horizontal forms means failing to get to grips with the political challenge and with the many potential pitfalls along the way. Our vision of a political organisation also means eschewing simplistic, ‘magic trick’, sound-bite ‘solutions’, favoured by some in the degrowth and related communities. Examples include Universal Basic Income, a Jobs Guarantee, sovereign money, Modern Money Theory, or partial but inadequate measures such as the Frequent Flyer Levy and Carbon Tax, or the now in vogue wealth tax. Of course, some of these policies might be part of a degrowth transformation, but none of those either alone or together, represents a theory of transition. How, though, can coordination be achieved between the two necessary means of securing a degrowth future, party-style political organisation and civil society activism with its practical projects? One model is to construct a kind of degrowth observatory, whose task would be to gather and disseminate information, not just on the various elements but on the way they contribute to the whole, shared project. Such an institution could help us to systematically map the movement and act as a necessary first step to more coordinated activities. This could be what one of us has elsewhere described as ‘prefigurative action research’, wherein the successes, triumphs, failures and defeats can be analysed to identify more precisely both what has to be overcome and (with contextual sensitivity) what works25. The intelligence that such an ambitious exercise would yield, for example as a standing programme of the International Degrowth Network (as a kind of Degrowth Observatory), could, perhaps, inform some kind of shared institution that might ultimately have a coordinating role, subject to a constituent assembly. That in itself would prefigure the new governing arrangements for the new society that is being striven for. Notes * The authors are the coordinators of the degrowth uk website. 1 The term ‘analectical’, comes from the work of liberation philosopher, Enrique Dussel it is a contraction of ‘anadialectical’ a fusion of two concepts, a) the dialectic, as a resolution of two opposites through a synthesis that transcends them, and ‘ana’, from the Other, giving critical voice to the oppressed and excluded. Our realisation of this aim, in this piece, can be only partial, but it is important that prescriptions and proposals are in the interests of the global popular majorities, and we try to reflect this. See globalsocialtheory.org/thinkers/dussel-enrique/ 2 https://degrowth.info/en/blog/neither-the-either-nor-the-or-for-a-sideways-degrowth 3 Fitzpatrick, N. (2025). ‘Degrowth’ and the implications of English language hegemony. In A. Nelson & V. Liegey (Eds), Routledge handbook of degrowth. Routledge. 4 Latouche, S. (2012). Salir de la sociedad de consumo: Voces y vías del decrecimiento (First Spanish edition). Ocataedro. 5 Latouche, S. (2012). La sociedad de la abundancia frugal: Contrasentidos y controversias del decrecimiento. Icaria. page 20. 6 Marcuse, H., Bosquet, Michel (André Gorz), Morin, E., Mansholt, S., & others. (1975). Ecología y Revolución Herbert Marcuse, Michel Bosquet (Andre Gorz), Edward Morin, Sicco Mansholt et al. (Nueva edición. First published in French by Le Nouvel Observateur, 1975). EBOOK. (Quotation is MB’s translation from the Spanish translation). 7 Pineault, E. (2025). Fossilised metabolism: The social ecology of capitalist growth. In A. Nelson (Ed.), Routledge handbook of degrowth. Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/reader/read-online/f0d99b9c-b15f-48cd-aa94-dca46806489a/book/epub?context=ubx 8 Dean, J., Heron, K. Climate Leninism and Revolutionary Strategy, Spectre Journal, 2022. 9 Kagan, C., & Burton, M. H. (2018). Putting the ‘Social’ into Sustainability Science. In W. Leal Filho (Ed.), Handbook of Sustainability Science and Research (pp. 285–298). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63007-6_17 10 Chertkovskaya, E. (2022). A strategic canvas for degrowth: In dialogue with Erik Olin Wright. In N. Barlow, L. Regen, N. Cadiou, E. Chertkovskaya, M. Hollweg, C. Plank, M. Schulken, & V. Wolf (Eds.), Degrowth & strategy how to bring about social-ecological transformation (pp. 56–71). Mayfly. 11 Bevins, V. If We Burn, London: Wildfire, 2023. 12 Dean, J. Crowds and Party, London:Verso, 2018, 125. 13 Dean, J. Crowds and Party, London:Verso, 2018, 125. 14 Dean, J. Crowds and Party, London:Verso, 2018, 21. 15 Dean, J. Crowds and Party, London:Verso, 2018. 16 Dean, J. Crowds and Party, London:Verso, 2018, 259. 17 Nunes, R. (2021). Neither vertical nor horizontal: A theory of political organisation. Verso. 18 Nunes, R. (2021). Neither vertical nor horizontal: A theory of political organisation. Verso. 19 Nunes, R. (2021). Neither vertical nor horizontal: A theory of political organisation. Verso. 20 Dean, J., Heron, K. Climate Leninism and Revolutionary Strategy, Spectre Journal, 2022. 21 Williams, R. (1973). The country and the city. Chatto and Windus. p. 36 Williams, R. (1982). Socialism and Ecology. SERA. Burton, M. & Steady State Manchester. (2012). In Place of Growth: Practical steps to a Manchester where people thrive without harming the planet. Steady State Manchester. pp. 39-40 Box: Historical memory and lived culture https://steadystatemanchester.files.wordpress.com/2012/11/inplaceofgrowth_ipog_-content_final.pdf 22 https://prometheusjournal.org/2025/08/05/in-defence-of-factions/ 23 Dussel, E. (2008). Twenty theses on politics. Duke University Press. Devine, P. (2002). Participatory Planning Through Negotiated Coordination. Science and Society, 66(1), 72–85. http://gesd.free.fr/devine.pdf 24 See Getting Real: – serious policies for the triple crisis. https://gettingreal.org.uk 25 Kagan, C., & Burton, M. (2000). Prefigurative Action Research: An alternative basis for critical psychology? Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 2(73–87). Teaser image credit: A caricature of the two visions – created from public domain sources. Author supplied.