Copyright gq

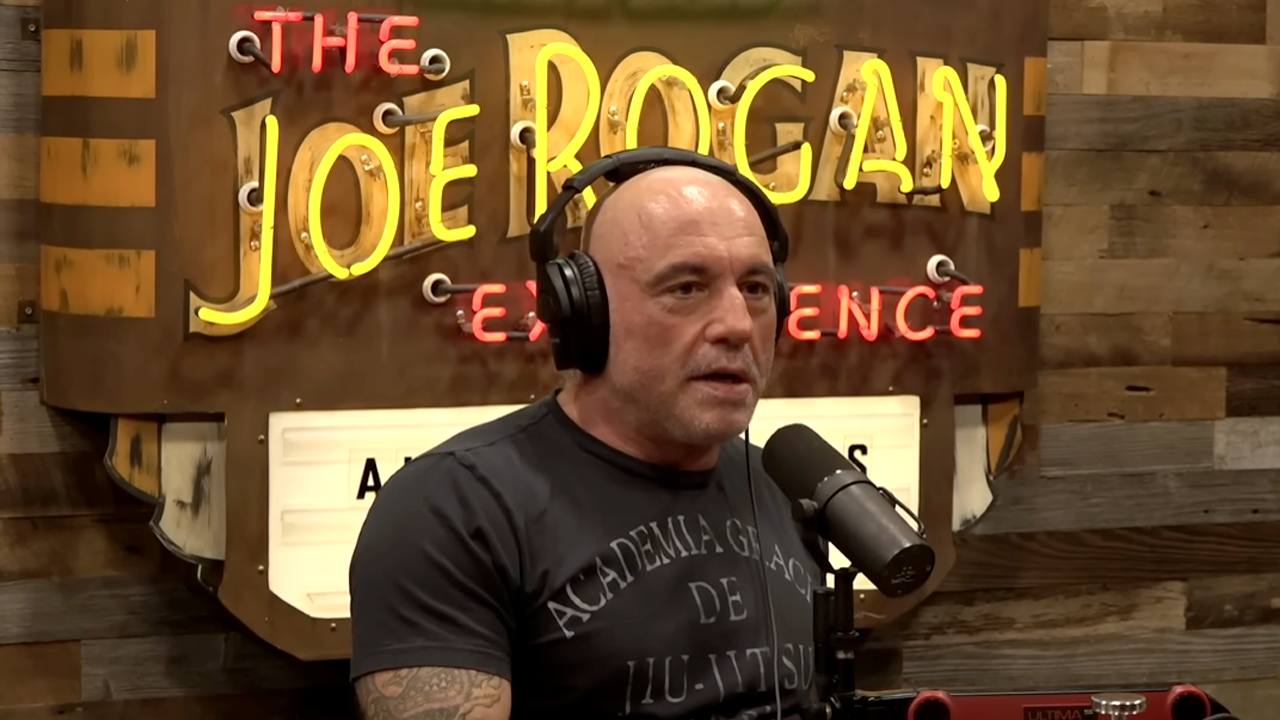

If you were alive in 2017—or better yet, like me, in your twenties and living in San Francisco—you probably heard a lot about “toxic masculinity.” I did, all the time, and it bugged me a little. Not because I felt personally attacked by the term (I am a woman, after all), but because nobody seemed entirely sure what the alternative was. How does one replace toxic masculinity without abandoning the concept of masculinity itself? To make matters worse, there was seemingly no way for men to escape the label. In a sort of nonsensical “if the witch drowns, she wasn’t actually a witch” train of logic, the only way to avoid the label was to “do the work” and own up to being toxic. The worst sin you could commit was to deny your toxic masculinity—which was apparently a symptom of toxic masculinity. Most reasonable people agreed that it was bad to be boorish, arrogant, overly confrontational, and aggressive. Most people agreed it was bad to objectify or disrespect women. But if those things were toxic, what would a non-toxic masculinity look like? Assuming a man “did the work,” did his future involve endless groveling and the disavowal of his masculinity entirely, or was he able to remain masculine in some way that wasn’t a problem? And how would we square this with the long history of heterosexual women sexually desiring masculine men, whatever that meant? (I distinctly recall some women denying that women were attracted to masculine traits, but as one of the many studies I conducted for my Substack on relationships and culture later suggested, women desire dominance in men more than men desire submission in women!) People did try to redefine masculinity, usually by replacing the “toxic” masculine traits with positive traits that, in fact, had nothing to do with masculinity at all. Being respectful, flexible, and attentive are good, but those traits have nothing to do with masculinity any more than they do with femininity. To me, the subtext to takes like these was, “Maybe masculinity and femininity just shouldn’t exist at all.” And that kind of gave away the game, didn’t it? Toxic masculinity was masculinity. Replacements for toxic masculinity weren’t particularly masculine, and could have easily been replacements for “toxic femininity” too (had that existed). So what should we have done with masculinity? We should have acknowledged that aggression and dominance were masculine traits, and traits that women liked … in the right context, in the right amounts. Instead of doing away with it all, we should have acknowledged these traits can exist in harmony with a healthy dose of … femininity. I know that the idea of reclaiming masculinity through femininity may sound a bit weird, but as men on Twitter say about a photo of a conventionally attractive woman who happens to have brown hair, hear me out. Back in the ’90s and ’00s, it was common for women to say they wanted men with a “feminine side.” Not in an academic, social justice “abolish gender” way, but in a “what could be sexier than a man who can bench press 250 pounds and tenderly read French poetry?” way. Women acknowledged that the fuckboys of the ’90s—the womanizers, the bar-fighters, the scrubs, as it were—did not make good or appealing partners. Saying a man was “in touch with his feminine side” acknowledged that masculinity was good, but unchecked, 100% masculinity wasn’t. This ethos didn’t call for abolishing masculinity or replacing it with some gender-neutral Soylent Man masculinity substitute that boiled down to “just be a nice person.” These women acknowledged their attraction to masculinity while also acknowledging the need for some checks on it. They wanted a guy who could beat another guy up in a fight, but had the restraint not to do it. They wanted a guy who could pin their hands above their heads (with consent) and then make them a frittata the next morning. They wanted a guy who would assertively negotiate for a better salary and make decisions in the workplace, then call his grandma on the commute home. They wanted a guy who could play a messy game of rugby, but wasn’t ashamed to sit on the Husband Bench in the mall while they went shopping. And as I’ve written before, a man who can show even a slight amount of curiosity about his partner’s feminine interests will serve himself and his partner well, even if he isn’t actually into “girly things” himself. At some point, the “feminine side” line fell out of fashion. Maybe, like many other expressions, it just became cringe. Maybe a bunch of jerks pretended to cry at When Harry Met Sally while continuing to be jerks, and the whole thing began to feel like a farce, the same way people complain about “performative men” who preach about bodies and spaces over matcha lattes while jugging ten situationships. But the ’90s really felt like the last time people had a reasonable idea of what it meant to be masculine in a way your average straight woman would still find attractive, without being a massive dick: just be in touch with your feminine side a little bit. We still see men who exemplify this archetype, though. Of course, they tend to be good looking (big shocker—women like hotness. I suspect men can relate to this preference as well!). Many of the male heartthrobs with the most appeal are not, strictly speaking, ultra-masculine, but they are still unambiguously men. Timothée Chalamet and Harry Styles are the subject of a great deal of straight female lust—but both of them would look wildly out of place in a lumber yard, let alone a bar fight at the Salty Spitoon (the dive that barred Spongebob for being too wimpy, for those of you who aren’t as cultured as I am). Some would argue that being emotional or sensitive isn’t innately feminine, or that aggression and dominance aren’t masculine. But those descriptions only offend people if they can’t conceive of the benefit of both the masculine and feminine sides within one person. Having a “feminine side” as a man doesn’t make you less of a man, nor does having a “masculine side” as a woman make you less of a woman. Even though the pushback tends to come from a progressive place, the dogmatic adherence to the gender binary ironically makes it difficult to accept a “feminine side” as a neutral or positive thing for a man to have. Men and women are different. We’re at a point culturally where everyone kind of admits this is true, but a lot of people are afraid to say how. Of course, every woman will desire different degrees of masculinity. It’s not worth it to try and hack your personality to match a perfect ratio of masculine and feminine, because that ratio doesn’t exist. But it’s also reasonable to say that you can have a healthy dose of masculinity without defaulting to the most extreme version of it. You can be an assertive decision-maker without interrupting everyone at work. You can be strong while still getting a little misty-eyed when the dog dies at the end of the movie. You can be aggressive without channeling it into crime or violence—what about football, or for that matter, arguing about zoning laws on Twitter? There are many ways to be a man without abandoning masculinity entirely. But to do that, we have to admit that masculinity is a real thing, and that many straight women like it.