Copyright scmp

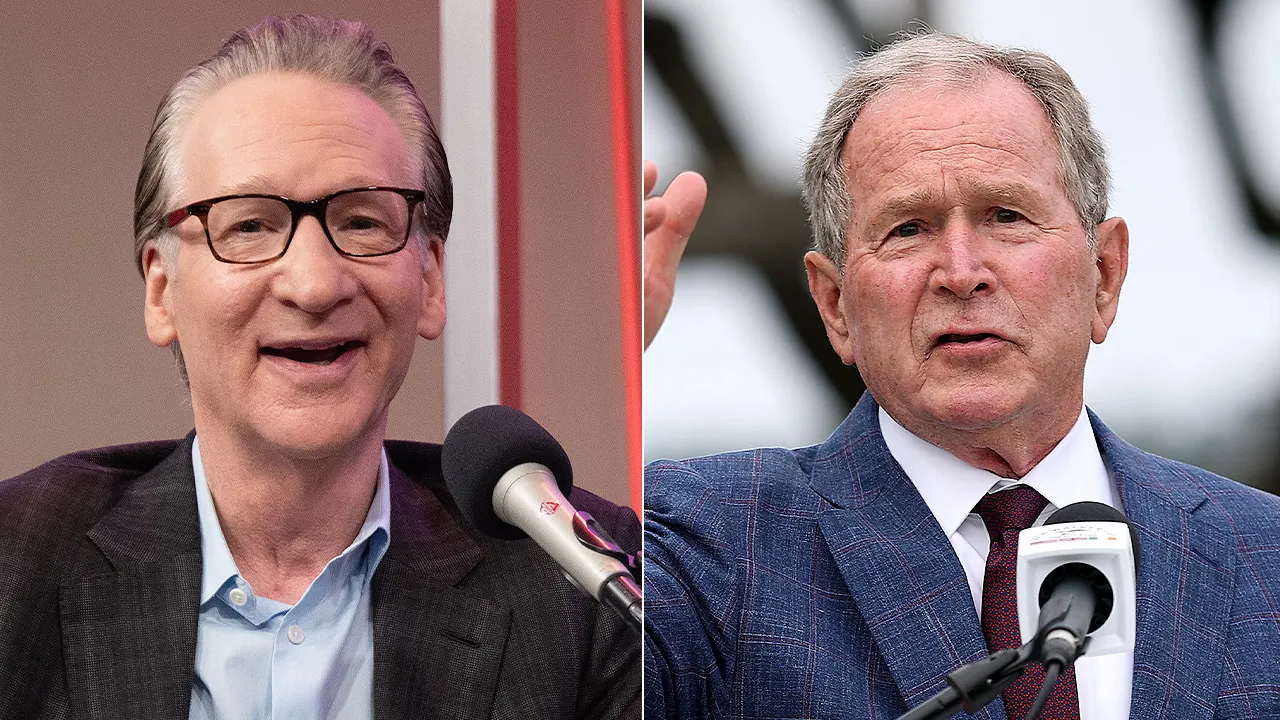

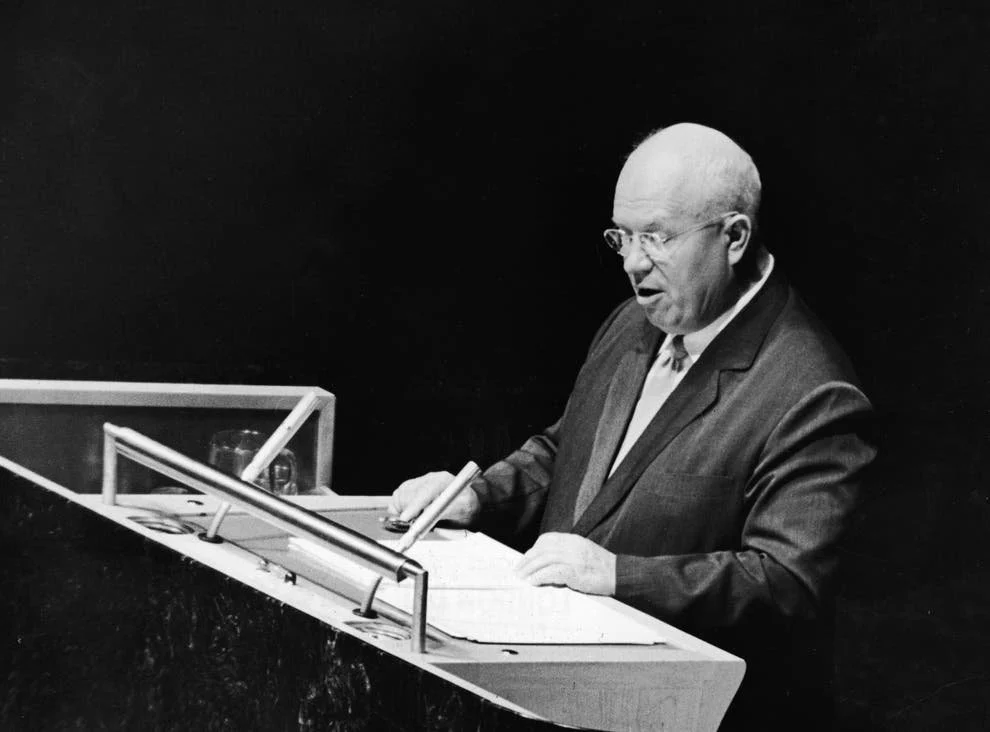

Would the Cold War have unfolded differently if Nikita Khrushchev had chosen a different interpreter? It is a decades-old thought experiment, born of the phrase translated as “we will bury you”, but it is chiming with today’s strategic rivalry between China and the US. Whether the statement, attributed to the then-leader of the Soviet Union in 1956, should instead have been interpreted as the less aggressive “we will outlive you”, the incident sheds light on a recurrent headache in modern diplomacy. Wittingly or unwittingly, mistranslations appear to be increasingly testing already strained nerves in Washington and Beijing, according to a report released earlier this month by the prominent US think tank Rand Corporation. The study, titled “Stabilising the US-China Rivalry”, accuses a number of influential China hands – all proficient in Mandarin and drawing on Chinese-language sources in their arguments – of a “hawkish” distortion of Beijing’s terminology. These “respected authorities” fuelled an increasingly common view that Beijing had “well-established, specific and uncompromising intentions that make almost any form of effort to create a meaningful equilibrium on specific issues pointless”, the study said. The policy research organisation’s analysts gave numerous examples in the 115-page report to support their argument that prominent China watchers “sometimes rely on a narrow subset of sources and take these sources out of context”. Their assessments could also “risk overlooking historical legacies, cultural framing and the often ambiguous or performative nature of Chinese political discourse”, the study warned. The research cited Rush Doshi, a senior National Security Council official in the Joe Biden administration, as well as Matt Pottinger, deputy national security adviser during President Donald Trump’s first term. The analysts also gave examples of apparent mistranslations or lack of context by Kevin Rudd, former Australian prime minister and now Canberra’s top envoy to Washington, and Nadege Rolland, former senior adviser to the French defence ministry. “Several of the authors have also translated Chinese terms with more hawkish English alternatives than the original Chinese language sources may imply,” the Rand report warned. A typical case outlined in the study was a 2021 book by Doshi – now director of the China Strategy Initiative at the US think tank Council on Foreign Relations – that translated the Chinese phrase xianshouqi as “offensive moves”. According to the report, Doshi argued in his book that this showed Beijing had shifted towards a more assertive, order-building grand strategy more than a decade earlier. But the study’s authors pointed out that the term – borrowed from a board game and literally meaning “first hand” – could be more precisely translated as “taking the initiative”. It “conveys strategic foresight rather than outright assertiveness”, the authors said. Chinese experts have pointed out that the phrase could be interpreted as referring to making an issue a priority in China’s policy contexts. The study also cited an article by Pottinger and two co-authors, published by Foreign Affairs in 2022, as an “example of an interpretation that favours a more negative view of China”. According to the study, the article claimed that a PLA textbook stated that President Xi Jinping’s use of “very sharp” to characterise China’s contradictions with Western countries had been taken by the secondary source to “mean violent”. However, the Chinese leader’s original phrase – in a 2012 speech – was feichang jianrui, which could be more suitably translated as very “acute” or “pointed”, the study’s authors said. This was especially so given the context, they added, pointing out that Xi was referring in his speech to ideological and systemic tensions with the West but not to any armed contests. Meanwhile, Waixuan Weiji, an influential WeChat account that focuses on English translations of political discourse in both China’s external publicity outlets and the foreign press, noted that Western scholars who truly master Chinese “remain few”. “Their understanding of Chinese is sometimes rather superficial and they may not accurately capture the ‘nuances’ between the lines,” the social media channel wrote in a note on Wednesday. “Yet the wording choices they make in translation often shape how the international community perceives China’s political discourse,” it added. The channel is written mainly by a translator with China International Communications Group. Beyond the cases cited by the Rand report, there have been frequent instances of translations in American strategic circles that have led to controversy in China-US relations. A notable example is an article by Pottinger and Mike Gallagher – a former chairman of the US House select committee on competition with China – that was published last year by Foreign Affairs. The two authors translated a remark by Xi to his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin in 2023 as “right now, there are changes, the likes of which we haven’t seen for 100 years. And we are the ones driving these changes together”. In the article, Pottinger and Gallagher used this line to argue that “Xi had revealed that he saw himself not just as a beneficiary of worldwide turmoil but also as one of its architects”. However, the full conversation – which occurred as Xi was wrapping up a visit to the Kremlin – was not captured in the short clip of the exchange. The footage showed that Xi’s remark could be more accurately translated as: “This is also part of the changes unseen in a century. Let’s work together to promote.” It remains unclear what “this” referred to. Mistranslations are not just occurring within strategic circles. They have also been increasingly appearing at the official level and arguably the wordplay is not limited to the US side. During a phone call in January for example, China’s top diplomat Wang Yi urged his US counterpart Marco Rubio to hao zi wei zhi, according to Beijing’s Chinese-language media release, which presumably was targeting a domestic audience. Wang was referring to a Chinese proverb that, when applied in the context of a warning, conveys something like “you had better know what you are doing or you will face the consequences”. But in China’s official English statement, the remark was moderated to “I hope you will act accordingly”. Rubio later denied that Wang had issued any warning at all, quipping that Beijing liked to “play games”. In an unusual personal insult, US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent two weeks ago lashed out at Li Chenggang – who holds the full ministerial post of International Trade Representative in the Chinese commerce ministry – as “unhinged”. Citing an anonymous senior American official, the Financial Times reported earlier this month that Li, a key member of China’s trade negotiation team, had threatened the US with “hellfire” if negotiations did not go his way. However, the report sparked widespread confusion and scepticism on social media in China, where there is no direct equivalent to the term “hellfire” in everyday language or culture. Many Chinese social media commenters have embraced the theory that the inflammatory word was merely the result of a mistranslation of the well-known idiom wan huo zi fen. The phrase, which can simply be rendered as “those who play with fire will get burned”, has increasingly been used by Beijing officials and state media to warn Washington against “interfering” on the Taiwan issue or pursuing “unilateralism” in trade. The episode did not derail the trade talks – a fresh round took place in Malaysia from Saturday to Monday – but it showed how translation can throw up conundrums in the high-stakes field of diplomacy when languages and political cultures are quite divergent. It was also reminiscent of the fallout from Khrushchev’s arguably mistranslated statement of seven decades ago, received by contemporary Western audiences as a hostile declaration of Moscow’s intent to destroy the other side of the Iron Curtain. But many modern scholars have suggested the phrase should have been translated as “we will outlive you”, a reference to the Marxist truism that socialism eventually replaces capitalism, rather than as an explicit threat. On social media, the Waixuan Weiji channel warned that the era of “official” versions being the absolute authority on the translation of Chinese materials was over. “The translations of others are continuously rising and their approaches and perspectives are becoming more diverse – at times even shaping how Chinese discourse is recognised overseas,” it said.