Copyright Forbes

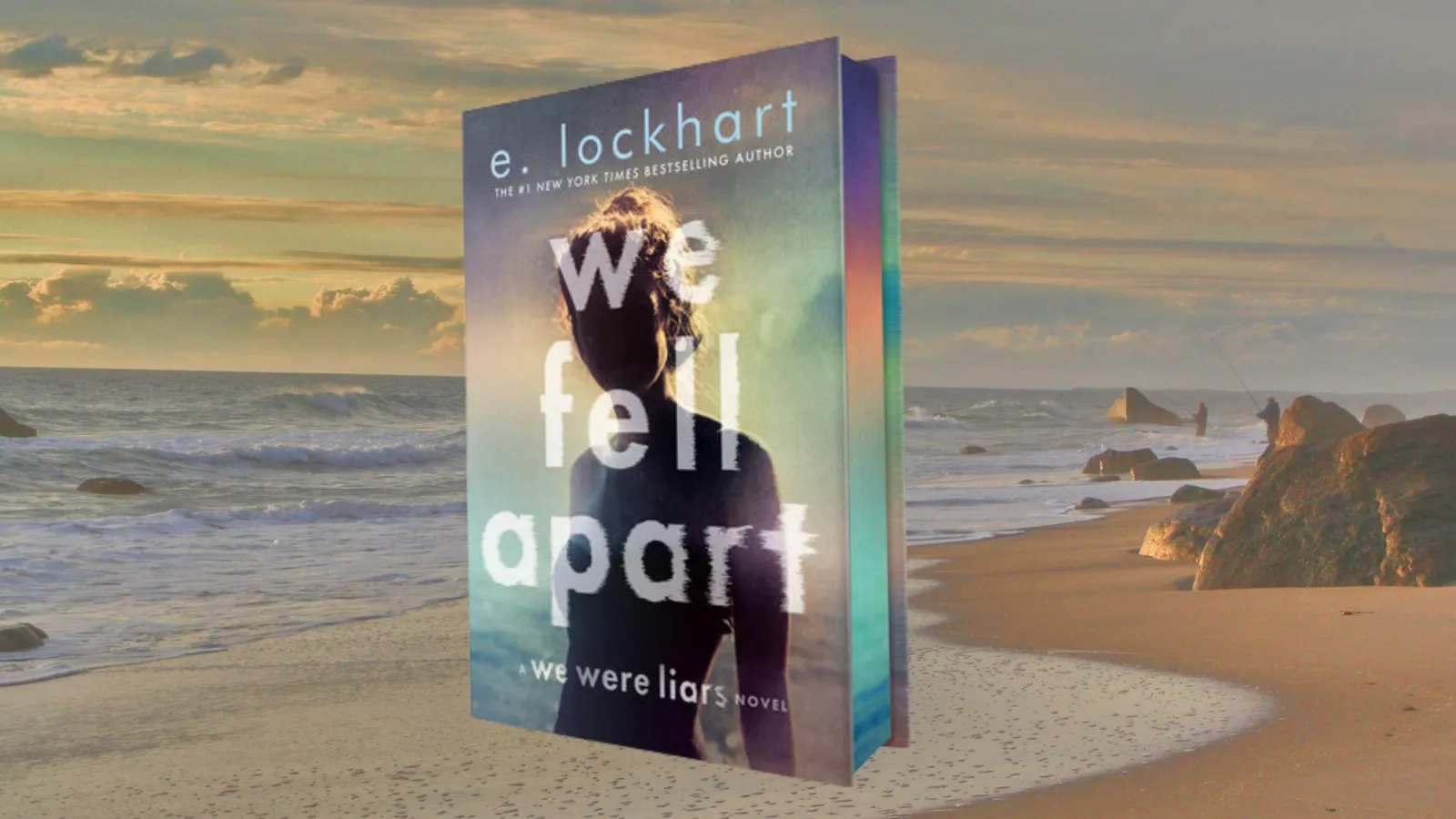

When I sat down to talk with E. Lockhart, the author of We Fell Apart and the mind responsible for the world of We Were Liars, I really wanted to ask her about the role indigo dye played in her latest novel. Indigo, if you do not already know, is ancient. The oldest extant example of indigo dyed cloth we have is 6,200 years old and it was found in Huaca, Peru. Before it was identified by Dr. Jeffrey Splitstoser and his colleagues (1). This was a big deal because, before the Huacan fabric was discovered, the oldest dyed indigo cloth we knew of was about 4,400 years old and came from Egypt. Without veering too far off track I want to impart two things: Indigo was cultivated and used in textile dyes in a lot of ancient civilizations, from India to Mesoamerica, but it requires some sophisticated technological advances to process. Indigo may have always been part of human communities, or it has been for a very long time. “Well, there's two reasons that the indigo dye made its way in there,” E. Lockhart told me. “At the start of Dodie Smith’s I Capture the Castle, the people in that family are dying all their clothes green. And I've read that book a number of times, Dodie Smith is good at her job. And it brings you into this world of people who are making making things, they're creative, this creative urge is like strung up all over the kitchen and it's sort of taking over their lives, like they're dying too many things green, more things than they want, because they're involved in the dying, and then everything is green. Now we've done it, everything is green. And they just have to accept it. And the dye pots last throughout the novel, I just loved that. I was looking for some way to reference that, a book that I love so much and has influenced me.” The other reason ties the author to her stories in a more indirect way; but it shows a little slice of her world building, how the blend of reality and make believe come together seamlessly in well-written fiction. “On Martha's Vineyard, where I often spend some of the summer,” Lockhart told me, “there is a wonderful place called Native Earth Teaching Farm. And the agenda is education for children, but also for people in the community. They have animals, tours and other kinds of events. One event that they have every summer for some years is an indigo pot. I think we've gone three or four times. You bring things to dye, and sometimes they have things for sale that you dye, you know, shirts, things like that. Everything goes into this community indigo pot. But there's rubber bands and ties, and books of different techniques for doing something more than plain tie dye.” In We Fell Apart, indigo dye, the processes of dyeing, the making of things for those we love is shimmering always just below the surface. It ties a mother to her son, it brings friends together, there is a point at which it pushes some characters apart. Understanding the inspiration behind this throughline a little better, I wanted to know why Lockhart choice this specific device. “I always have found this indigo dyeing just kind of magical and immersive,” the best-selling author told me. “I'm not a crafty person. It's unusual for me to be in that situation. And your hands go all blue and your clothes go all blue. And you're all together with these pieces of indigo fabric blowing in the wind drying off. “The woman who runs the Native Earth Teaching Farm is nothing like June is in the novel,” Lockhart said with a smile. “There , the way the indigo pot functions is different from what I did in the novel.” I’ve written a lot about the ways that textiles and apparel can serve storytelling, and this is as true about novels as it is in storytelling on film. We all wear clothing, we all pull information about those around us based off of what they are wearing, positive or negative it is something we all do. In a novel, what the author dresses their characters in, and the way those characters interact, or don’t, with the clothing in their lives, it tells us readers about who they are. “I kind of took those two elements and then brought them into the story that I wanted to tell,” Lockhart said of June’s indigo pot. “It's a way, when Matilda first arrives at Hidden Beach, for her to get immediately immersed in their way of life. And it is a very particular way of life with certain kinds of rules and values; this was a way for those values to be made active.” Those values, the ways they are brought together, are clues about the author as well. E. Lockhart, a best-selling author many times over, has a PhD in English Literature, her dissertation focused on the 19th century novel. Throughout her (rather impressive) backlist there are endless nods to literature and fairy tales from the western canon. I felt like this was purposeful, not necessarily in terms of individual books or characters, but more like their author leaning into the tale types (2) that meant most to her. “I think that my imagination is just very influenced by the work that I read when I was studying for my degree,” Lockhart said, “as well as by the work that I read now and the work that I read as a child. Most of the time, it's not so deliberate, it is something that just happens in the writing. I was well, well into We Were Liars before I realized how much of Wuthering Heights was in that book. I think I was conscious of how much King Lear was in that book, but the Wuthering Heights was a little bit of a surprise to me. And then I realized, you know, how much Emily Bronte's book was kind of informing my thinking about some elements of the story that I was telling. I think it just happens, I knew that I was writing something in that vein, that I was in conversation with those books. But then, you know, along came Hamlet, and along came The Odyssey, and along came the story about The Donkey Skin. And along came Narnia, which shows up in Family of Liars, too. There's a very direct connection, the one to the other. But, you know, it's not like I planned that out. ” Lovely reader, King Lear is a Cinderella story (3), it felt important to me to make sure you understand that a piece of fiction being classified as a Young Adult Fiction, that is a system set up to help parents know which books are appropriate for various ages. The category has no connection to quality of writing. You probably already know this, but there are plenty of people who don’t; it’s not uncommon for adults to assume there’s something lesser about novels written for a teenage or young adult audience. Authors like E. Lockhart regularly publish work that proves YA can be literature; We Fell Apart is merely her latest volume which should be thought of, read and received as literature, regardless of the expected or intended audience. I love storytelling in all formats. I am always interested in the process, and considering the hundreds of references Lockhart weaves into her writing, I asked her how she found a place to start when sitting down to begin writing a novel like We Fell Apart. In my imagination, it sounded overwhelming, the blinking cursor on an empty document, and the thought that must proceed all the work it takes to transform an idea into an exceptionally polished book. “It is overwhelming,” the author told me. “In the case of We Fell Apart, I started with a couple stories that I think were already speaking to each other and wanting to kind of be in the conversation with those stories, and those included Iris Murdoch's The Good Apprentice, which I think is also very much in conversation with Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte and We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson.” If you’ve read the Liars books (We Were Liars and the prequel published second, Family of Liars) or seen the Amazon Prime series, We Were Liars, this new book is in that same universe. Though, and the author makes a point of saying this before the book begins, this story stands alone, not quite off to the side of the Liars. Our protagonist, Matilda Avalon Klein, has rather disinterested parents; she’s never met her father and the story begins with her mother running off with a man, leaving Matilda with the boyfriend she’s leaving behind. Don’t worry, Saar is a very good man, though she’s soon leaving at the invitation of her father, the reclusive painter, Kingsley Cello. Every book Lockhart writes, from The Disreputable History of Frankie Landau-Banks to the books in the Liars world, has fairy tales woven through them. Often Cinderella (3), and I wanted to know how those archetypes fit into this story, which features, mostly, a new cast of characters. “I think the Cinderella story appears in We Fell Apart in the shape of a painting that Matilda's father Kingsley does,” Lockhart told me. “And also in the story that Kingsley tells, of The Three Brothers, which is also a Western fairy tale. Unlike in the Cinderella story, The Three Brothers, despite being placed into competition with each other, end up in complete harmony with one another. The Cinderella story looms large, and parallel stories loom in the imagination of Kingsley Cello. I think readers can read We Fell Apart all on its own, but if they have read Family of Liars, they will see, I hope, a deepening of that story's resonance.” I asked the author about the names of her characters? How did she pick them? Were they places we should be looking for clues? “Sometimes,” Lockhart told me. “But also sometimes I am very simply wanting people to be able to differentiate a large number of characters. So, Matilda has three syllables, Tatum has two syllables, Meer and Brock each have one. And ‘Meer’ and 'Brock’ are single syllable names that have different sounds at the center of them and different kinds of endings. Things like that can help a reader who's being introduced to a large cast of characters to hold on to who's who. I know that for readers of We Were Liars and Family of Liars, Penny, Carrie, and Bess, those are all New England, WASP-y type names, two of which end in IE or Y, that E sound. So, that's harder to parse. Sometimes it's just practical.” I asked about the character, Holland Terhune, who becomes friends with Matilda. She’s a wonderful character and her arc, though not always the focus, is fundamentally important to the narrative. “Holland had a different name and now I've forgotten what it is,” Lockhart said. “But I wanted a non-binary name because the character, although she uses “her” pronouns, thinks of herself as not on the binary gender spectrum, or as opposed to the gender binary, that is how she phrases it. But the book is set in 2012, so I didn't think it was realistic for her to use “they, them” pronouns in the kind of old school WASP-y family that she's in.” This type of plotting and planning, the thinking and remembering this quality of writing requires, Lovely Reader, it fascinates me. I told Lockhart I was curious about how she decided what components to include in her characters, what made something important enough to her to include. “I'm interested in how certain things seem unspeakable,” the author said to me. “A simple thing is that people tell a lie. But a more interesting thing is, people trying to tell the truth, but they can't really give voice to the truth. So then what do they do? Maybe they distract you. Maybe they say the truth in a way that might be misleading, but it's still the truth. Maybe they adopt a grab bag full of poultry, you know, to avoid being confronted with the truth. But I think people are doing this all the time.” The poultry bit you will understand, once you’ve had a chance to devour this wonderful book. “And the truth might be a big secret, like it is in the novel,” Lockhart said, “but it also just might be the truth of how you feel, or the truth that your heart was broken or the truth that you're insecure about something. There's a million things that all the time we are not saying. And even if we do not want to be liars, we still are not always telling the whole truth. That just interests me as a thing about language, as humans, humans and language together. Communication. I think I'm just always, always thinking about language.” As I’ve said, this book is Liars adjacent, but one of the biggest differences between this book and those, to this reader, is its tone. “It felt like, with the third book, was a time to tell a love story that, at first, seems like a terrible idea,” Lockhart said. “It's a love story with a happy ending. I think I was in the mood to write a love story that turns out well. And in a way, I guess that is a subverting of expectation, if you've read Liars and Family of Liars. Those love stories, in very different ways, do not turn out well. I don't mind telling people that upfront, in a way, because I don't think it spoils the twists and turns of the plot. I think I'm always trying to offer some kind of hope or feeling of possibility for the future in my books.” “We Fell Apart", the newest novel by best-selling novelist E. Lockart, is now available at your favorite bookseller. MORE FROM FORBES ForbesExploring Class And Character In Costumes For Prime’s ‘We Were Liars’ForbesAs If—Mona May’s New Book Celebrates ‘The Fashion Of Clueless’