Copyright thespinoff

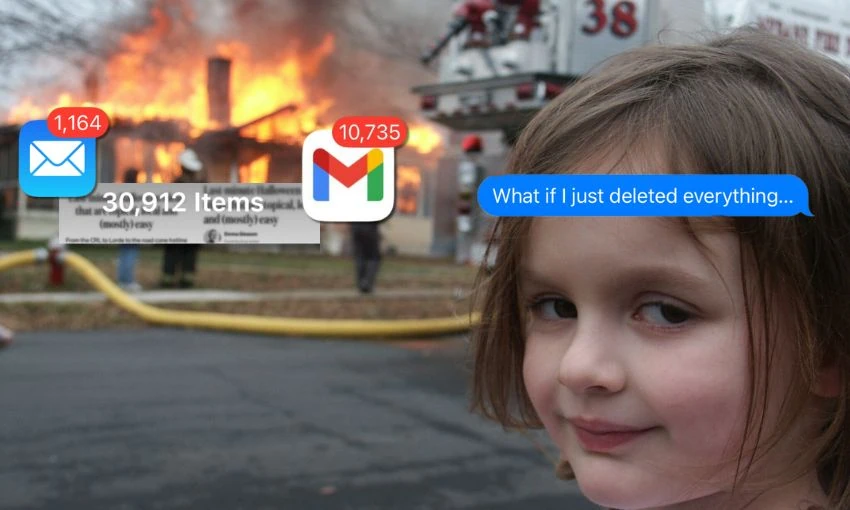

Housekeeping my hoarding and learning to let go. To anyone sneaking a look, the home screen of my phone shamefully reveals 1,183 unread emails. Inboxes are one of the biggest sources of clutter, according to studies into the “emerging phenomenon” of digital hoarding. It’s embarrassing. I envy the presumed mental clarity of Inbox Zero devotees. Those little (or big) numbers say a lot about a person. When much of what constitutes our personal and professional lives takes place in the software and hardware of digital spaces, not having your house in order can feel like a social failure in our online village. Ascribing moral judgments to it could send you into a spiral about your disorganisation, lack of priorities, unreliability and general mental messiness. Applying that old saying of “tidy house, tidy mind” to our digital property, it’s easy to draw a line from digital clutter to psychological disorder. I have 30,908 photos, videos and screenshots saved on my phone. There are meals I made in lockdown and Himalayan mountain ranges, screenshots of dumb tweets taking up as much valuable space as photos of my friends. Tidying them all up requires time and a triage system. Some businesses promise to do it for you, efficiently removing duplicates and blurry photos. But like handing over the keys to your house, it comes with trepidation. Luckily there’s infinite space in the cloud. For as little as $1.69 per month you can ignore the problem and sprawl instead. Cloud storage is supplied by data centres, the “invisible engines of our digital world”. New Zealand has 56, with 20 more in the pipeline. By 2028 our public cloud spend is predicted to double, hitting $9.6 billion. Digital files are bigger than ever and we have more of them, which puts increased demand on hardware and infrastructure. It wasn’t that long ago (or perhaps it was – I got my first phone 22 years ago) that we’d have to delete the literal dozens of texts on our phones to create space for new ones. A single message cost 20 cents to send. Phones evolved to have more space, more functionality and more stuff. (So much stuff.) The apps themselves contain their own kind of clutter. Our infinite feeds deliver hundreds of posts and stories to wade through, like an unsurmountable pile of postcards and letters. There’s more junk on my laptop. Recently upgrading my 2011 Macbook Air to a new model, I spent a whole weekend tidying up the old one. Decluttering and spring cleaning that small metal box felt like a Sisyphean task. With seemingly infinite space comes infinite clutter. Unlike cupboards full of empty glass jars and a pile of unpaired socks, it’s not physically there. No one sees your shameful hoarding unless they glimpse your home screen. In the memoir Destroy This House, Amanda Uhle details growing up with a hoarder parent, speaking of the shame and secrecy of living in a house bursting with stuff. Hoarding disorder is thought to affect a not insignificant chunk of the population. A 2017 study from the University of Otago showed 2.5% of participants met clinical criteria for pathological hoarding, while 4% had “sub-clinical hoarding issues”. Categorised as a mental health condition by WHO, it’s at the extreme end of the mess spectrum. Digital stockpiling is less visible than its real-world counterpart, but a chaotic digital environment can be just as draining as living with physical clutter. In a UK survey earlier this year, 69% of people described themselves as “digital hoarders”. Some experts say it’s “overloading” our brains and causing stress, anxiety and avoidant behaviour. Others believe digital hoarding is a unique disorder. Obsessive and unrealistically high standards can make you prone to excessive clutter. A 2024 study of university students showed that “individuals with higher levels of maladaptive perfectionism exhibit amplified digital hoarding tendencies when emotionally attached to their digital data”. It found students formed “emotional attachments” to their digital data, which gave them a sense of comfort and security. We’re scared to let go. Amid all that ephemeral mess are precious treasures. But there’s also literal trash. Old supermarket lists and nonsensical jottings about things like “overton window Birkenstocks” and “bread” litter my notes app (there are 1,577 of them in there). Some of the digital clutter is truly ephemeral, like notifications. All those messages, missed calls and push alerts (the average US smartphone user gets 46 per day) form a pile of things that need our attention and it’s stressing everyone out. A 2degrees-commissioned survey earlier this year showed 37% of New Zealanders feel “overwhelmed, panicked, or anxious” by the number of notifications they get. Most of them are emails (cited by 60%) and social media (cited by 65%). For the past couple of years I’ve been actively trying to spend less time on my devices and be more intentional when I do. It’s not just me. The 2024 Where Are the Audiences study revealed, to some surprise, that time spent on social media and user-generated video had dropped for my demographic (15-39-year-olds) and there’s growing consensus that we’ve passed peak use of these platforms. But tidying up all the crap on my old laptop seemed antithetical to that goal. More screen time for less data? My eyes were burning by the time I finished sorting everything onto the new one, moving things to the trash, putting my house in order. Shifting from one home to another is widely considered one of life’s more taxing events (though exactly how much is debated), with frequent relocation a “substantial contributor to stress”, according to University of Auckland research. I’ve lived at 22 different addresses. But faced with a decade’s worth of files in my downloads folder, tidying up a lifetime of computer crap can’t be far behind. Some are forgoing digital clutter and online spaces entirely. There’s a “growing ecosystem” of youth-led “neo-Luddite” groups in the US, the subject of a recent New York Times story (read on my phone, 22 tabs open) and another in Business Insider (read on my laptop, 58 tabs open). A reaction to the increasing hold technology has over most aspects of modern life, the movement favours analogue tools and encourages, among other actions, the deletion of social media accounts. iPhones were smashed at a recent rally in NYC, representative of the deluge of daily notifications and hours spent on social media. Much like setting the house on fire and walking away, destroying a phone feels easier than dealing with that insurmountable mess of screenshots, files and memories (let alone system change). But where a physical photo destroyed in a blaze is likely gone forever, its digital counterpart may live on, floating in the cloud or synced to an old device in the bottom of a cable-filled box, some real-life clutter. Digital hoarding offers the allure of preservation. Businesses promise to get your lost files back. There’s even cyber insurance, which includes data recovery and system repair, for if it all goes up in smoke.