Copyright thespinoff

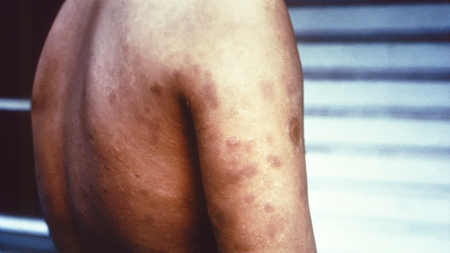

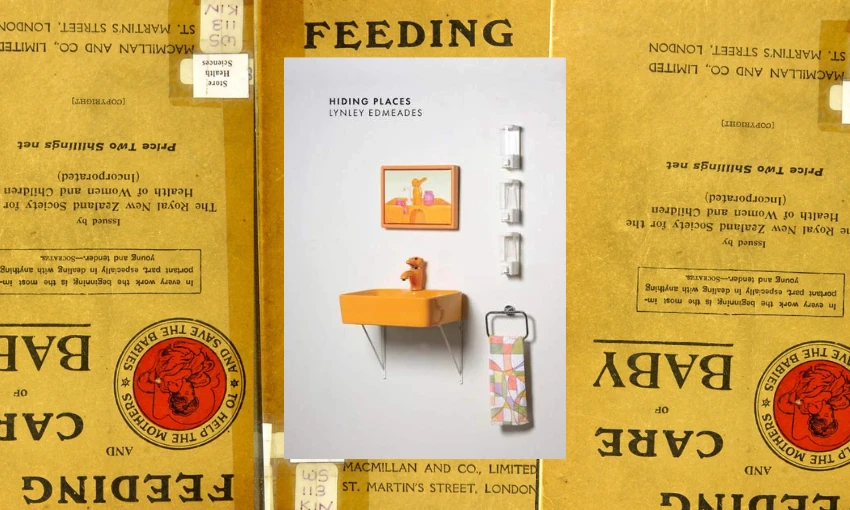

Lynley Edmeades explains how and why her new book about her experience of early motherhood, Hiding Places, draws on excerpts from Truby King’s Feeding and Care of Baby. Like many babies, my son was a terrible sleeper for the first two years of his life. This statement is so banal and commonplace, I’m embarrassed to even write it. But this experience plunged me into much sleep-deprived and neurotic contemplation of the parenting advice that was offered to my partner and I in droves in those first years of our son’s life. The advice we received from our midwife and, subsequently, our Plunket nurse was, amongst other things, perplexing. We were told to let the baby “get on with it” (i.e. cry until he slept) so we could do the same – get back to work, return to productivity. We quickly became accustomed to mottos like “don’t make a rod for your own back,” or “you have to teach your baby how to self-soothe”, the latter lauded as a great gift that would serve our child well for the rest of his life. But why? What was so wrong with my baby needing me, I found myself asking? The idea underpinning this – if we take it to the extreme, perhaps – was that we should teach our children to never depend on anybody, most of all the people who were there to love and protect them. Very sleep-deprived and high on hormones, I was not sane in those early months; my partner was the grounding force and encouraged me to not beat myself up when our baby was not working like everyone said he would. With already-low self-esteem, I would chalk up the failure of my son to do the things he was supposed to do as being a product of my own failure. He failed to sleep because I had failed to teach him and therefore, by extension, I had failed to do my job as a mother. One health professional even told me my son would run the risk of getting brain damage if he was awake for more than an hour and half at a time. In my darkest days, my heart would sink when he woke from a nap because the clock would then start ticking, the battle to get him to sleep starting all over again. I spent weeks and months scrolling through sleep advice websites, going to early childcare groups to figure out how other mothers weren’t losing their minds. In retrospect, I realise that my son was what they call a “low sleep need” baby. It took four years for me to learn that concept. Had the advice worked for us – and my son behaved the way I was told babies “normally” do – I wouldn’t have needed to explore where these ideas came from. When I was slightly more compos mentis, a little less insane (inasmuch as anyone ever returns to sanity after having a child), I started to question the foundations of this rhetoric; my academic training implored me to. Where did these ideas come from and what was hiding behind them? What kind of ideology lurked in the shadows of this advice? To quote Deborah Levy, “there is never nothing beneath something that is covered.” My reading led me to the history of The Society for the Promotion of the Health of Women and Children, aka Plunket, founded in 1907 “as part of a Western-world infant welfare movement that aimed to improve the survival and fitness of future citizens in the interests of ‘national efficiency’.” As many readers will know, Plunket is the legacy of Sir Frederic Truby King, who was a New Zealand health reformer and Director of Child Welfare from 1921–27. In the early 20th century, King was superintendent of Seacliff Asylum. With an interest in animal husbandry and eugenics, King’s early research into paediatrics led him to devise a milk-based formula which led many babies who would have otherwise suffered from malnutrition to thrive, making New Zealand’s infant mortality rate the lowest in the world at the time. His book The Feeding and Care of Baby, first published in 1913, became the founding document upon which mothers and fathers for generations to come would refer and be referred to in their early years of parenting. Among other things, the book emphasised strict routines for feeding and sleeping, along with advice for “handling the baby” and “forming a character.” The book also offers suggested methods for preventing your child from becoming an “exacting tyrant” or, even worse, a “mouth breather.” In my recent book Hiding Places, I draw on excerpts of Feeding and Care of Baby, quoting passages from the book and placing them alongside excerpts from family letters, secretive medical records and a diaristic documentation of early motherhood. King’s 1913 words are no doubt entertaining reading to contemporary readers, especially those who have been schooled on the likes of D. W. Winnicott and his notions of attachment theory, which place relationships central to any child welfare. But, to find King’s work “absurd” (as is a common response to my book) is to take something of an anachronistic reading of his work, which is not my intention. I don’t wish to dismiss the pioneering King did toward child welfare, particularly at time in our history when we were subject to declining mortality and poor nutrition. Through fragmentation and poetic exposition, Hiding Places attempts to trace lines of inherited and intergenerational attitudes toward parenthood and mental health throughout the 20th and early 21st centuries. As a 1980s child raised in rural New Zealand, I use the book to examine the threads of this foundational document – survived through institutions like Plunket – throughout my childhood and into my own matrescence. The book tries to make connections between some of King’s early regimes and my contemporary failure to be a “good” mother, whatever that might mean. Because Hiding Places flirts with a confessional style, it has invited some intimate reader responses. I have had some women tell me about their own, often undiagnosed, post-natal depression; some older mothers have recalled lying to the Plunket nurse about how many times the baby was waking in the night; and that yes, the baby definitely slept in her cot in another room and definitely not in the bed with the mother, which was the ultimate sin. On a very basic level, we might see this as the long reign of the patriarchy – how, in the “beginning”, a man came to tell all the women how to raise their baby in the most efficient and effective way. We can also read King as a product of his time and historical milieu – his belief system was not out of place in a global context, regardless of our understanding of eugenics today. In fact, much of what he did do for New Zealand mothers in the first few decades of the 20th century – pioneering of infant milk formula, for example – was incredibly forward-thinking. And yes, we can trace the layers of this internalised patriarchy through the generations to our present moment, through our mothers and our grandmothers, to realise that these messages have morphed and wobbled and they have indeed changed. But, for me, it was understanding the roots of that infant rhetoric that allowed me to decide for myself how I wanted to be a mother. My book is not a take-down of King or any parent who has – for a myriad of reasons – sleep-trained their baby or any other fucking thing they needed to do to survive. Understanding King and his legacy is a reminder of the necessity of historical context for any consideration of our current situation. Without history and context we have no way of making intelligent decisions about the future. Hiding Places by Lynley Edmeades ($35, Otago University Press) is available to purchase at Unity Books.