Copyright The New York Times

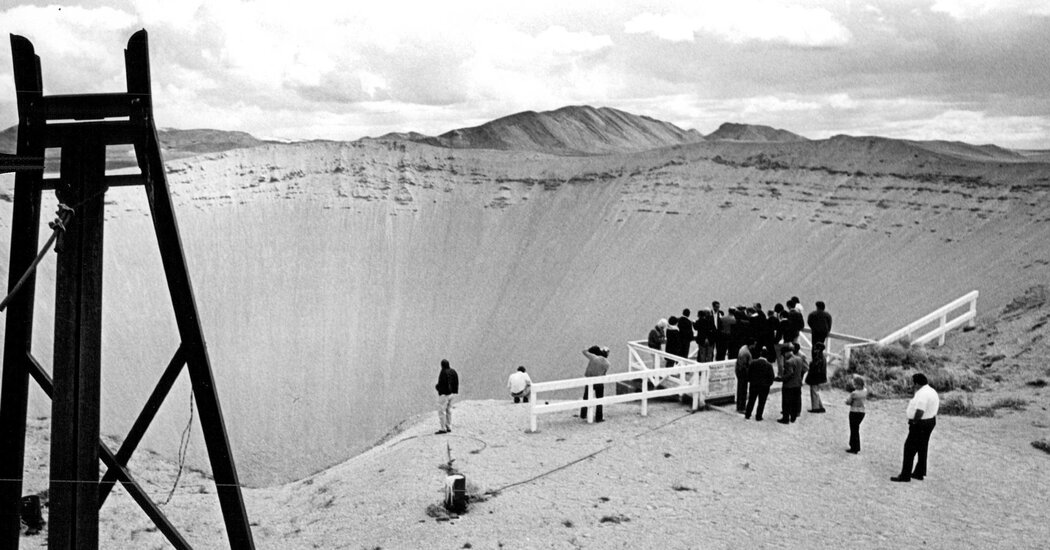

Hours before meeting President Xi Jinping of China on Thursday, President Trump made a confounding proclamation: He wanted the Pentagon to “start testing our nuclear weapons on an equal basis” with Russia and China. Why was the statement so puzzling? For a start, the Defense Department doesn’t test nuclear weapons. The Energy Department does. The other problem with Mr. Trump’s pronouncement is that Russia and China don’t test their nuclear weapons. Of the world’s nine nuclear powers, only North Korea has not observed a moratorium on underground nuclear blasts for decades. It’s hard to see what parity Mr. Trump seeks to achieve. Mr. Trump could clear this all up himself, of course, by explaining what he meant when he posted the missive on social media. He has thus far refused, saying only that his decision didn’t relate to China. “It had to do with others,” he told reporters, without naming countries. “They seem to all be nuclear testing.” The president’s ambiguity is worrisome not only because America’s public can’t know what he means, but because America’s adversaries don’t. The vague statement could be received in Beijing and Moscow in the most literal terms — even if not intended that way — ushering us all toward a new reality in which resuming nuclear testing is an open question, rather than a closed chapter. As we have written in our series, “At the Brink,” the prospect that the world powers could one day again take up nuclear testing has long loomed over the post-Cold War world. Rising geopolitical tensions and the development of a new generation of nuclear weapons have indeed recently brought those fears closer to reality. In the past, the governments of the United States, China and Russia have said they are not willing to break with the testing moratorium, though commercial satellite imagery has shown that all three have construction projects underway at their respective testing grounds. While Moscow and Beijing have said little about that activity, Washington has stated it is building new infrastructure for what are known as subcritical nuclear tests, or underground experiments that test nuclear components of a warhead but stop short of creating a nuclear chain reaction, and therefore, a full weapons test. I saw this construction for myself last winter when I toured the Nevada test site, about an hour’s drive north of Las Vegas. During the Cold War, the U.S. government regularly detonated nuclear weapons there; the sunbaked flats still bear the scars of craters caused by those explosions President John Kennedy pushed all nuclear weapons testing underground in 1962 in response to environmental and health concerns. Over time, the United States has constructed a labyrinthine system of underground tunnels and shafts to continue the practice, until they were halted altogether in 1992. One of those series of tunnels is now home to PULSE, the Principal Underground Laboratory for Subcritical Experimentation, where scientists and engineers experiment with weapons-grade plutonium using explosives to gain new insights into exactly what happens inside a thermonuclear explosion, beyond what was learned from the full-scale tests decades back. Walking about 1,000 feet underground with a hard hat, boots and protective goggles, I could see why the government agreed to bring me down there. It was to show that the roughly $2.5 billion in taxpayer dollars was being invested in new equipment for subcritical systems — not to test warheads that could flatten entire cities. Throughout the subterranean lab, construction workers were installing infrastructure for new machines that will eventually help ensure that our nation’s aging nuclear weapons still work. (The oldest plutonium in the current stockpile is about 80 years old.) Subcritical tests may answer questions about plutonium aging, but not all, according to some American weapons scientists. The only way to do that, they say, is by starting full-scale testing again. Pulling that off won’t be quick or easy. Because America has not tested a nuclear weapon since 1992, it would take more than a year to prepare all of the diagnostic equipment and technical instrumentation and to rebuild the infrastructure in underground shafts as deep as 5,000 feet to do a full explosive weapons test. Past presidential administrations have ruled out resuming that activity because of a simple cost-benefit analysis. Having conducted more than 1,000 tests, the United States has tested more nuclear weapons than any other nation; Russia has conducted 715 tests, and China 45. As a result, the United States has far more scientific knowledge about how its weapons work than does its adversaries. A resumption of U.S. testing in Nevada or anywhere else would essentially give Russia and China an incentive to resume their own testing — and potentially catch up. Aside from the scientific and geopolitical calculus, there’s a human risk to resuming testing as well. In virtually every place nuclear weapons have been tested, evidence of chronic illnesses and cancers has surfaced in the surrounding populations. The effect on the environment is also lasting. The United States, China and Russia have not conducted an underground nuclear test since signing the 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. But the United States and China never ratified the document, and Russia rescinded its ratification in November 2023, a step backward for international arms control. Nevertheless, with the exception of North Korea’s tests, the moratorium on testing has managed to hold. So why say anything at all? It could be that Mr. Trump simply experienced some nuclear envy this week after President Vladimir Putin of Russia announced the tests of a new nuclear-powered cruise missile and a new nuclear-powered underwater drone. These systems may one day carry nuclear weapons, but for now they’re simply systems under development. Perhaps Mr. Trump wants the Pentagon to investigate developing similar capabilities, or accelerate the tests of the missiles and air-dropped bombs that are already in the U.S. arsenal. The Defense Department does control these delivery systems and will respond to the commander in chief’s directive. The president has routinely said he wants fewer nuclear weapons in the world, not more. His words and actions, however, raise questions about how serious he is about it. In his first term, Mr. Trump did order the Energy Department to be ready to conduct “a simple test, with waivers and simplified processes” inside of six months — rather than the two- to three-year time period of his predecessors. That never happened, despite talk within the White House to consider it in 2020. But such a short-notice test, I was told by an administration official then, wouldn’t be for scientific reasons; it would be political, to send a message to adversaries. We’re lucky to find ourselves living in an era where the deadliest weapons aren’t routinely being exploded by leaders for show. The world should remain steadfast in maintaining the status quo before we find ourselves in a dangerous, unpredictable new era where that practice becomes normalized. Mistakes of the past shouldn’t be repeated just because memories fade.