Copyright National Geographic

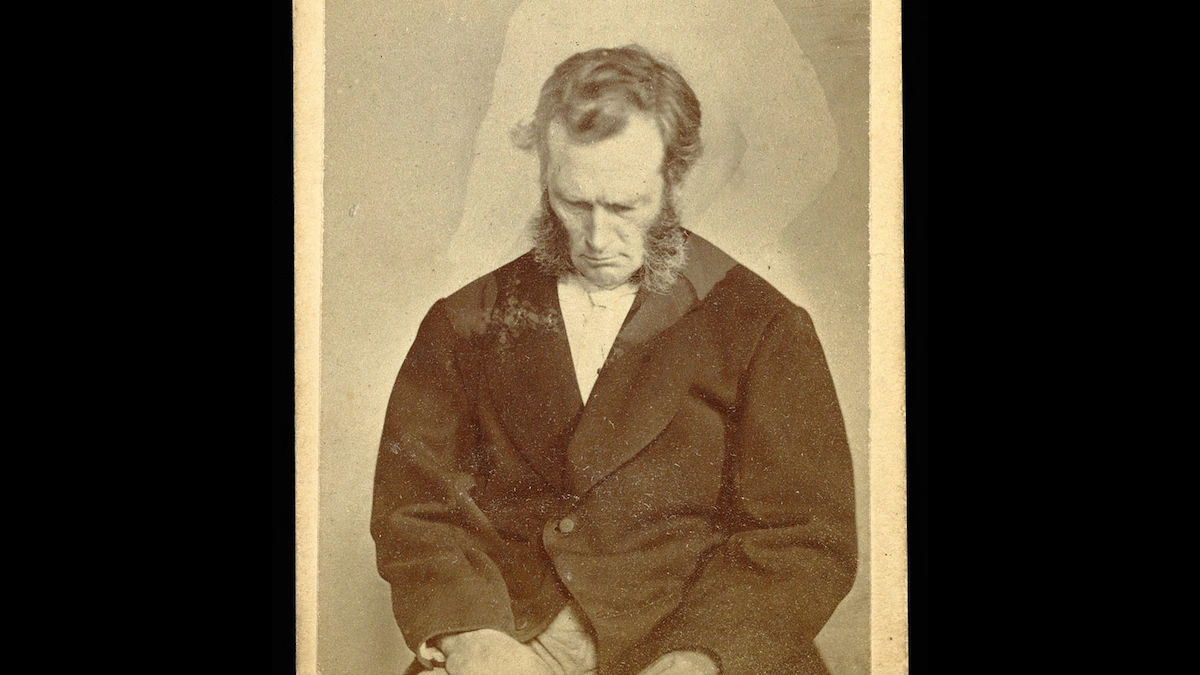

In 1862, jewelry engraver and amateur photographer William H. Mumler was developing a self-portrait in his Boston studio when a ghostly image began to surface. Just below his own image in the photo appeared a young woman in a flowing dress, her features blurred by a ghostly halo. Mumler showed the picture to his friend, possibly as a joke, and mentioned the woman looked like his deceased cousin. Soon it was being passed through Boston society. It didn’t take long for the local Spiritualist community to learn of the miraculous photo. The news was blasted to their followers via fringe religious journals: spirits had finally been captured on film. In fact, the woman who appeared next to Mumler was likely Hannah Frances Green, who worked nearby as a photographer and spirit medium, and would later become his wife. Mumler hadn’t properly cleaned the photographic plate before using it again, leaving a remnant of Green’s image behind. But Mumler—a technological whiz and amateur chemist who had already racked up a variety of patents—soon realized he could make a lot of money offering ghost photographs of the deceased for $10 a sitting (more than $300 today). It was a fertile time for photography and the paranormal to collide. The first-ever photograph had been taken around 1827, of a French rooftop. A decade later, the first humans were captured in pictures. The public was captivated by this new technology’s ability to show realities few had ever seen, from distant countries to wildlife and nature. At the same time, scientific discoveries like the X-ray were proving that the human eye couldn’t see everything. (Visit the most haunted sites in Charleston) Meanwhile, in the late 1840s, three sisters had sparked a religious fervor in a small town in upstate New York. Claiming to communicate with ghosts via strange tapping noises coming from the walls of their farmhouse, the Fox sisters became a national obsession. The public had also recently been introduced to long-distance communication in the form of the telegraph. It wasn’t that far-fetched, writes Peter Manseau in his book The Apparitionists, that mediums might stretch that communication into another plane entirely: the spirit world. Spiritualism, a religious movement connecting the realms of the living and the dead, was born. LIMITED TIME OFFER Over the next few years, scientific challenges to Spiritualism arose—but then the Civil War plunged the nation into a state of fear, grief, and mourning. By the time Mumler was passing around his unique photograph, the country was already a year into the conflict. Photography had become a way for families to memorialize their loved ones. Mothers had portraits taken of their sons before they left for battle, and soldiers carried photos of their families to the frontlines. Back in Boston, Mumler began experimenting in the dark room with double exposures and other tricks to give the appearance of spirit visitors. Pensive children, concerned parents, and loving husbands surfaced, often appearing to embrace the living. The appetite for spirit photography was limitless in the bereaved nation. (Harry Houdini's unlikely last act? Taking on the occult) But he got sloppy. In Boston, a former client spotted his own wife being used as a “spirit” in another photograph. The only issue: she was very much alive. Evading his detractors, Mumler moved to New York, and opened a new studio on Broadway. He lasted only a year before a fraud investigator posing as a client brought him to trial. In court, his opponent was a New York newspaper called the World, supported by a group of scientists and photographers. Their joint aim was to ensure that the public’s belief in the camera was not eroded by fraudsters. Mumler was on trial, but so was photography. One side was arguing for science, the other, for religion. Both believed they were fighting for the objectivity of this new technology: the camera. The prosecution tried to show how photography could be manipulated, but their efforts backfired. Unable to ascertain Mumler’s methods nor disprove the existence of the spirit world, the judge acquitted him, admitting at one point that he’d often seen spirits in the courtroom. This unexpected result was taken by some as validation of spirit photography, and may have helped spread it overseas. For those still immune to the Spiritualists’ claims, photography was unveiled as a medium for deception. Some photographers would later argue that the trial brought more harm to the profession than if Mumler had just been allowed to practice within the confines of Spiritualism. “Mumler was key in introducing the possibility of fraudulence into ways of thinking about photography,” says Michael Leja, an art historian at the University of Pennsylvania, who wrote about the trial in his book, Looking Askance. “Prior to that, the testimony of people seeing Civil War photographs in galleries in New York was so powerful—they were almost unbearably real images of death and dismemberment. That was photography: it was truth.” The skepticism seeded by Mumler’s trial persists into our modern era. In a way, says Leja, “spirit photography is a precursor” to imagery created by artificial intelligence, and to our struggle to distinguish truth from deception. A few years after the trial, in the early 1870s, Mary Todd Lincoln showed up at Mumler’s studio in disguise. The resulting photograph shows a barely-visible shadow of Lincoln towering behind Mary, his translucent hands resting comfortingly on her shoulders. The image was not unusual: Lincoln’s ghost haunted America after his assassination, circulating in prints, photos, and books. For many, it was a comforting reminder of a paternal presence during the nation’s most trying era. Spiritualism would battle photographers, scientists, and even other religious movements in the coming years. Churches viewed the photos as parlor tricks at best, heresy at worst. However, in an era of rapid-fire scientific discovery, as believers were being pulled away from the church, practices like spirit photography were providing what some took as scientific evidence of their faith. (When the world went wild for talking to spirits) “For people who had their faith shaken by traditional Christianity, this offered a way of not giving up on it,” says Cadwallader. “Spirit photographs are comforting, like ghost stories are comforting. They’re saying that there’s more out there, that you continue in some way.” In 1875, another spirit photographer would be brought to trial. Edouard Buguet was a French Spiritualist who also, thanks to another undercover investigator, found himself in a Paris courtroom. Despite his confession, live demonstration of his photo manipulation techniques, and year-long prison sentence, Buguet’s Spiritualist followers refused to believe he was a fraud. “Nothing could convince people who believed in spirit photography that it wasn’t real,” Cadwallader says. “You can’t argue someone out of the feeling of being visited by a loved one who’s passed, or the feeling of grief that sends them to that photographer in the first place.” Broader societal belief, however, was waning. Released from the Civil War’s cycle of mass death, a variety of Victorian-era mourning practices—from wearing jewelry made of the hair of the deceased to spirit photography—faded from American life. Then, in 1914, World War I broke out and spirit photography resurged. One particularly active group of spirit photographers, called the Crewe Circle, preyed on the recently bereaved.