Copyright talkingpointsmemo

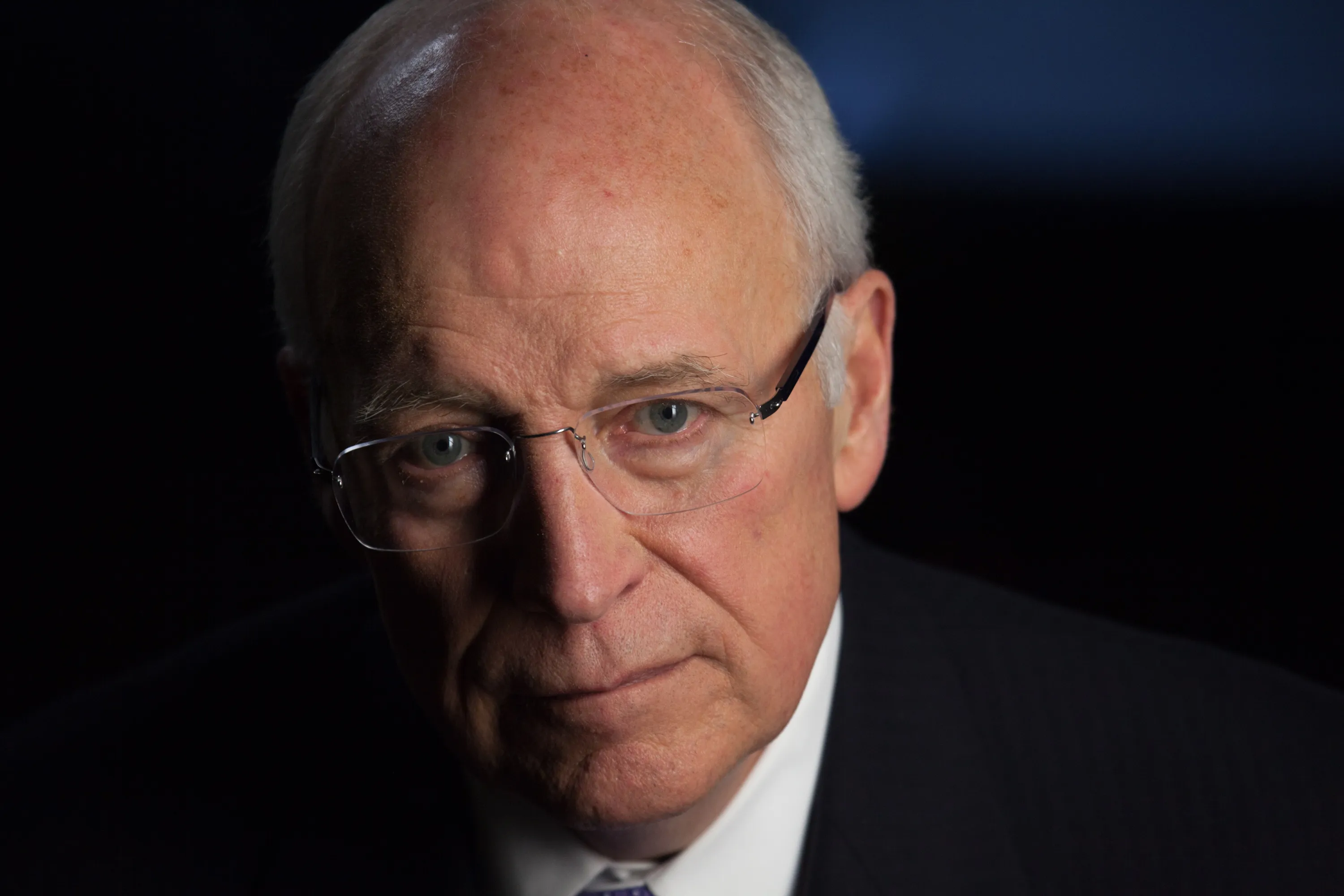

Editor’s Note: I mentioned in today’s Morning Memo that while TPM doesn’t do obituaries, we had for years a draft of one in the can for Dick Cheney. He was too central of a figure in the early years of TPM not to have something substantive to say upon his death. In the end, Cheney managed to outlive our meager draft. I went looking for it when the first alert of his death hit my phone early this morning. I soon got a text from former TPMer Brian Beutler: “Welp that Cheney obit I pre-filed to you ~15 years ago is finally good to go!” Unable to find it immediately, I enlisted the help of our tech guru Matt Wozniak, and in a dusty old CMS covered in cobwebs, he found it. Brian wrote it in 2012, prompted by Cheney’s heart transplant that year. The draft obituary, like Cheney’s new heart, held up better than I expected. And where our draft doesn’t hold up, it’s amusing … mostly in Cheney’s favor. I had long ago given up publishing it. Too much time had passed, Brian left TPM the following year, updating and revising it subordinated to more pressing news. But it’s an interesting time-capsule artifact from a period when our memories of the Bush II years were fresher, the wounds no longer raw but also not fully healed. Not contemporaneous, but also not further clouded by the passage of another 13 years and the upheavals of the Trump era, during which even Dick Cheney found himself isolated and abandoned by the Republican Party. So with apologies to the sacred order of obituary writers, whose work I deeply respect, here it is in full, foibles and all: Dick Cheney: 1941-????? (original title) To most Americans, the tales of Vice President Dick Cheney’s extraordinary power were an abstraction — or perhaps a myth concocted by political nemeses to suggest that dark forces were at work in Washington, D.C. By outward appearances the Cheney of lore required a leap of imagination. In rare public appearances, he cut a quiet figure, hunched and severe; competent, not omnipotent. But the Cheney of legend more closely resembled the genuine article than the solemn, manicured functionary who spun national policy on Meet The Press. Out of view, he bestrode the government like Colossus. Over time, as the Bush administration sank into ignominy, Cheney’s influence waned. He left office one of its most reviled figures, and spent the last years of his life battling heart disease and lashing out at enemies in between long stretches of solitude. He died TK in TK of TK. He was TK years old. Decades of public service, beginning with a Capitol Hill fellowship under a staunchly conservative member, ending with top positions of authority in the executive branch under Republican presidents, left Cheney uniquely suited to unite the frequently incompatible realms of ideology and party politics. It also left him well acquainted with the hidden levers of power that pepper the government. His approach to the Vice Presidency reflected these two defining traits. Cloistered from the public, he dramatically extended the boundaries of the executive branch’s accepted authority. As an adherent to wildly unpopular policies, he consistently operated at the outer edge of these boundaries, and at times on the wrong side of them. Cheney forged an expansive view of White House power amid Nixon-era scandals that hobbled the executive branch, where he’d risen from mid-level bureaucrat to become chief of staff to Gerald Ford. This wasn’t just a manifestation of myopia or institutional territoriality. His perspective didn’t change as a five-term congressman, who climbed within GOP ranks to become the party’s second most powerful member in the House. As a conservative, yes, he sought to limit the size of federal government, particularly vis-a-vis domestic affairs. But he remained opposed to legislative efforts to constrain President Reagan’s actions within his own branch — Congress’ prerogatives didn’t include intruding on the so-called unitary executive. When those powers were finally in his reach, he employed them with ruthless efficiency and a career’s worth of bureaucratic skill. With each limb Cheney grasped the four fenceposts circumscribing executive power — Congress, the courts, the press, and internal actors within federal agencies — and pushed outward, until his administration had so much running room it scared even members of his own party. His will to power, and commitment to purpose, would have been something to admire, if the results for the country, his administration, and the people who stood in his way hadn’t been so devastating. The crucial manifesto for understanding this period of Cheney’s life is Angler, a thorough and astonishing chronicle of Cheney’s years as Bush’s number two by Barton Gellman. It begins with a parable that defined the first half of the Bush era. During his years in office and in the final years of his life, Cheney would joke about the highly unusual circumstances behind his ascent to the Vice Presidency: First he declined it; then he agreed to lead the search for the position he would eventually fill; then, perhaps reluctantly, he gave the job to himself. Throughout that process, he compiled comprehensive dossiers on the most powerful men in Republican politics. This sort of vetting is standard practice for lawyers and party operatives, but to the man who would be handed an enormous governing portfolio, it was also a huge source of leverage over potential troublemakers. One such troublemaker was former Oklahoma Governor Frank Keating — a VP short-lister, who during the Bush-Clinton transition vied to be the new President’s first Attorney General. He had the relevant experience and enjoyed the support of influential conservatives, but he also bore the hallmarks of an independent law enforcement official, disinclined to simply rubber-stamp administration prerogatives. That’s not what Cheney wanted. In December, 2000, Bush picked relative novice John Ashcroft for the job. Weeks later a damning story appeared in Newsweek, detailing seemingly improper gifts Keating’s family had received from a prominent, well-connected donor — information, according to Keating, that Newsweek could only have obtained from Cheney or his inner circle. “It obviously came from Dick Cheney or one of his people,” Keating told Gellman. It was an enormous breach of confidentiality — the sort of offense that could end a lawyer’s career. But for the other former VP hopefuls — including GOP Senate leaders like Jon Kyl and Bill Frist, and maverick members like Chuck Hagel — it was dead fish in the mailbox. Keating had been dispensed with, and any one of them could be next. Once sworn in, and unconcerned with the fact that Bush had lost the popular vote, Cheney began pursuing maximal policy goals, and testing the limits of the White House’s Article II powers to achieve them. Unlike his predecessors, he participated in his party’s weekly Senate legislative luncheons, and assumed de facto control of key administration policy councils. He thus enjoyed unprecedented control over all levels of decision making, and for that reason quickly found himself at loggerheads with members of his own party — some of them White House officials. In the Spring of 2001, Cheney picked a radical constitutional fight with Congress in an effort to shield his White House energy task force deliberations from public scrutiny. His argument was unprecedented: For legislators, or their official auditor, the Government Accountability Office (then known as the General Accounting Office), to access task force documents “would unconstitutionally interfere with the functioning of the executive branch.” The fight drained the new White House of precious political capital, and aroused suspicions even among the administration’s conservative supporters. GAO comptroller David Walker turned to the courts, arguing that Cheney sought a precedent that would “work a revolution in separation of powers principles [and] would drastically interfere with Congress’s essential power to oversee the activities of the executive branch.” Walker’s complaint went nowhere — the court refused to rule on the merits of the case. But when the conservative legal foundation Judicial Watch — an unlikely adversary — convinced the D.C. district and appellate courts that Cheney should be compelled to submit the disputed materials privately, Cheney opened a second front in the war and asked the Supreme Court to stop the lower courts in its tracks. The gambit technically failed — the high court declined to intercede — but his efforts created significant procedural problems for the plaintiffs and the lawsuit eventually died. The outcome crippled Congress and the GAO. The Courts hadn’t ruled against them, but the practical implication was clear: If the White House wanted to hide its activities from oversight, no other government entity would do anything stop them. Not every Cheney power play paid off so handsomely. His uncompromising effort to enact the first of two huge Bush tax cuts in the administration’s first 100 days nearly failed. He and his lieutenants targeted and alienated a small group of moderate GOP senators who wanted to scale back the White House’s ambitions, on the theory that in a narrowly divided Senate negotiation amounted to surrender. In the end the tax cut passed, followed by another round two years later when Republicans enjoyed a larger majority. In between, Cheney’s ruthlessness drove moderate Vermont Republican Jim Jeffords out of the party, and tossed control of the Senate to the Democrats — a huge setback for a President who came into office facing profound questions about his political legitimacy. Cheney stacked the executive branch with loyalists anywhere loyalty might yield policy dividends. His hand-picked apparatchiks Jay Bybee and John Yoo — Justice Department lawyers tasked with interpreting law for the entire executive branch — rubber-stamped torture and surveillance programs that shocked the conscience and ran afoul of international and domestic law. When Bybee and Yoo gave way to men of greater principle who jeopardized the administration’s warrantless wiretapping program, Cheney and his allies launched an egregious intimidation campaign against them and a handful of other executive branch lawyers who dared question its legality. Rather than bring the controversy directly to Bush — a man who fancied himself a decider — they attempted an infamous end run around the Justice Department officials who stood in their way. In a midnight ambush at George Washington University Hospital, Cheney’s allies pressured a confused, infirm John Ashcroft — who’d temporarily had handed over his duties as Attorney General to a skeptical deputy — to sign off on the program once again. They failed. But their lawlessness inspired a rebellion that nearly brought the entire executive branch to its knees. Bush learned of the brewing mutiny hours before dozens of top officials, including the FBI director, were prepared to resign en masse from his administration, and likely consign him to a one-term presidency. Bush went on to win a second term, but as the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan dragged on and his popularity sank, Cheney’s influence waned. (A February 2006 quail hunting excursion during which he shot his elderly friend Harry Whittington in the face didn’t help matters.) When Barack Obama took office in 2009, Cheney broke silence early and publicly attacked the new President’s leadership, using a familiar, but manufactured air of gravitas designed to make even banal observations sound wise and insightful. In July 2010, Cheney was outfitted with a device that mechanically pumped blood throughout his body. In March 2012, he underwent a heart transplant. It [ONLY?] sustained him for TK months. Richard Bruce Cheney was born on January 30, 1941. He is survived by his wife, Lynne, daughters Elizabeth and Mary, and six grandchildren. –Brian Beutler