Copyright Ars Technica

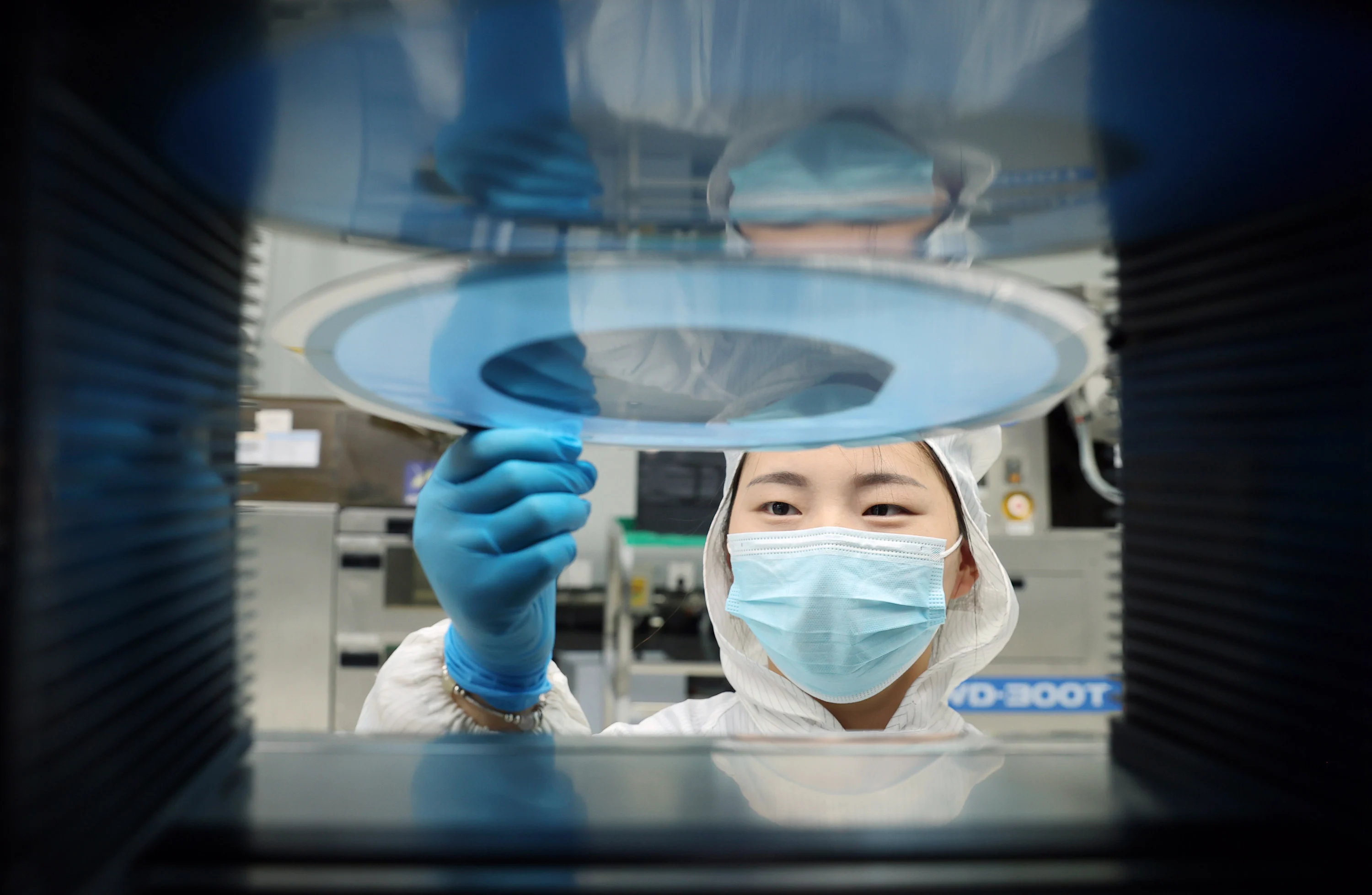

To the south of the Monte Cristo mountain range and west of Paymaster Canyon, a vast stretch of the Nevada desert has attracted modern-day prospectors chasing one of 21st-century America’s greatest investment booms. Solar power developers want to cover an area larger than Washington DC with silicon panels and batteries, converting sunlight into electricity that will power air conditioners in sweltering Las Vegas along with millions of other homes and businesses. But earlier this month, bureaucrats in charge of federal lands scrapped collective approval for the Esmeralda 7 projects, in what campaigners fear is part of an attack on renewable energy under President Donald Trump. “We will not approve wind or farmer destroying [sic] Solar,” he posted on his Truth Social platform in August. Developers will need to reapply individually, slowing progress. Thousands of miles away on the other side of the Pacific Ocean, it is a different story. China has laid solar panels across an area the size of Chicago high up on the Tibetan Plateau, where the thin air helps more sunlight get through. The Talatan Solar Park is part of China’s push to double its solar and wind generation capacity over the coming decade. “Green and low carbon transition is the trend of our time,” President Xi Jinping told delegates at a UN summit in New York last month. China’s vast production of solar panels and batteries has also pushed down the prices of renewables hardware for everyone else, meaning it has “become very difficult to make any other choice in some places,” according to Heymi Bahar, senior analyst at the International Energy Agency. In 2010, the IEA estimated that there would be 410 gigawatts (GW) of solar panels installed around the world by 2035. There is already more than four times that capacity, with about half of it in China. Many countries in Africa and the Middle East, even in petrostates such as Saudi Arabia, are rapidly developing solar power. “It’s a very cheap way to harness the sun,” says Kingsmill Bond, an energy strategist at think-tank Ember. Its analysis suggests that, helped by rapid growth in solar and wind energy, renewables generated more electricity than coal-fired power plants during the first half of this year. Progress in energy and other areas has damped some of the pessimism around global warming. In 2015, the UN predicted temperatures would rise by 4° C compared to pre-industrial levels by 2100. It now projects a rise of 2.6° C, if climate policies are followed through. But for delegates set to gather in Belém, Brazil, next month for the COP30 climate summit, any jubilation will be tempered by the knowledge that the renewables revolution is a long way from being fulfilled. Emissions from the energy sector rose for the fourth straight year in 2024 to a record high, while the slower growth in US renewables means an ambitious target to triple global capacity by 2030 will probably be missed. “It’s not job done, [IEA analysis] does throw some genuine caution out there,” says Mike Hemsley, deputy director at the Energy Transitions Commission think-tank. Renewable energy has lowered wholesale power costs, but that has not necessarily fed through into the prices that consumers pay, while users in many countries have not yet switched to electricity for things like transport and domestic heating in the numbers required to reduce fossil fuel usage. Calculations by the Energy Institute, the sector’s global body, show that the supply of oil, gas and coal for energy—electricity generation, heating, industrial usage and transport—in 2024 rose by more than the supply of energy from low-carbon sources, which also includes nuclear and hydropower. That has led some to argue that renewables are merely helping to meet climbing energy demand, rather than replacing fossil fuels. “The world remains in an energy addition mode, rather than a clear transition,” said Andy Brown, president of the institute, as it launched its report in August. “Renewables is the place to be” At a solar farm operated by ReNew, one of India’s biggest green energy companies, hundreds of panels glint in the sharp desert sun of surrounding Rajasthan. India, the world’s third largest carbon emitter, wants to develop 500 gigawatts of clean-energy capacity by 2030, and earlier this year reached 243GW—meaning more than half of its current installed power capacity is now from renewables. “Every group in India is now saying: ‘You know what, renewables is the place to be,” says Sumant Sinha, chair and chief executive of ReNew. Saudi Arabia, blessed with both oil and sun, has developed around 4.34GW of solar capacity as it tries to free up more oil for export, rather than burning it in its own power stations. It wants to build up to 130GW by the end of the decade. “It’s massive, what’s going on,” Marco Arcelli, chief executive of utility ACWA Power, which is part-owned by the kingdom’s sovereign wealth fund, told the FT earlier this year. The company is developing 30GW of renewables in Saudi Arabia. South Africa has authorised at least 6GW of renewable energy capacity since President Cyril Ramaphosa removed the capacity limit on private electricity providers in 2022, breaking years of reluctance among the ruling African National Congress to challenge the dominance of state monopoly utility Eskom. Middle-class households in the country have also rapidly installed solar panels on their roofs to cope with years of planned rolling blackouts due to power shortages. It is part of a worldwide trend for smaller installations as homes and businesses tire of waiting for governments or big utilities to fix power shortages. Solar panel installations of less than 1MW accounted for about 42 percent of global installations last year, according to BloombergNEF, almost double the 22 percent recorded in 2015. Factories, mosques and farms in Pakistan have covered their roofs in Chinese-made solar panels to try to avoid surging tariffs for state-provided power. “We’ve displaced tens of thousands of diesel generators,” says William Brent, chief marketing officer at Husk Power Systems, which has installed about 400 “mini-grids” of solar and batteries across Nigeria and India. These are helping pharmacies store medicines and shopkeepers keep drinks cool at around half the cost of power from the grid. The construction of vast solar arrays in deserts and small installations on rooftops have largely been driven by the same underlying trend: falling costs. The huge surfeit of production capacity in China, which produced about eight out of 10 of the world’s solar modules in 2024, has pushed the cost of panels down by almost 90 percent over the past decade and dragged overall capital expenditure costs down 70 percent, according to analysts. Yet even in places like India, fossil fuels still hold sway. Coal still generates more than 70 percent of the country’s power output and remains politically protected, employing hundreds of thousands directly and many more indirectly in some of India’s poorest regions. “India still has a massive way to go,” says Hemsley at the ETC. PM Prasad, chair of state-owned Coal India, told the FT earlier this year that it was reopening more than 30 mines and launching up to five new sites, arguing that renewables were not yet capable of meeting fast-growing energy demand. The painful process of acquiring large tracts of land for solar arrays in a country with millions of smallholder farmers has also led to delays across the renewables sector, many Indian developers grumble. More than 50GW of renewable power projects are waiting to connect to an overstretched transmission network, estimates the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, a think-tank, and cleantech consultancy JMK Research. Even as solar panels become more popular in Sub-Saharan Africa, millions of homes and businesses still rely on expensive and polluting diesel generators, and roughly 600 million people lack access to power. Many people also lack the means to pay commercial rates for electricity, even before factoring in the extra levies needed to finance the cost of new transmission lines, a key enabler of renewables projects around the world. Electricity storage capabilities also need to dramatically improve if countries want to rely more heavily on intermittent wind and solar farms and phase out backup fossil-fuel capacity. Large-scale batteries are being deployed rapidly—spurred again by China’s prolific manufacturing output. James Mittell, director at developer Actis Energy, says costs have fallen so much that it is already possible in many markets to build large-scale battery and solar systems, which can deliver power with similar consistency to gas-fired power plants, but at lower cost. “It’s a complete game-changer,” he says. But progress is also mixed on the second phase of any “transition” to renewable power: persuading consumers and industries to switch to equipment that runs on electricity rather than combustion processes using fossil fuels. The share of electricity in final energy demand has flatlined in the US and the EU over the past few years, with the growth of electric cars offset by the difficulty of getting people to switch away from gas or oil heating systems to low-carbon electric ones such as heat pumps. “For electricity [generation] we have a success story,” says Bahar, at the IEA. “For other sectors, it’s way more complicated.” Massive growth in China China and some parts of south-east Asia stand out in terms of the portion of energy supplied by electricity increasing—in China’s case, from about 12 percent in 2000 to about 30 percent in 2023—as millions of citizens start driving electric cars and factories switch away from fossil-fuelled boilers. Ember points to data showing that renewables met 84 percent of China’s new electricity demand last year as evidence that coal-powered generation in the country is nearing its peak. “We’re confident renewables can meet all China’s [power] demand growth,” adds Hemsley at the ETC. But even here, challenges loom. Major electricity market reforms introduced by Beijing in July mean renewable energy developers no longer get a fixed price akin to that received by coal-fired generators and are instead more exposed to market forces. “They clearly don’t want to harm the build out of renewables, but they just want it to be done on a more commercial basis,” says Neil Beveridge, who leads Bernstein’s energy analysis in Hong Kong. But the IEA warns it will lower returns and cut the growth of renewables. “That [impact of the reform] is the biggest uncertainty in our outlook,” adds Bahar at the IEA. A far sharper slowdown is already under way in the US, where incentives introduced as part of former president Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act in 2022 are rolled back by the second Trump administration. Tax credits have been cut and major projects blocked—spooking investors and leaving existing developers trying to stay afloat. “It’s very difficult to make big capital decisions based on this,” says Reagan Farr, chief executive of Silicon Ranch, a solar developer. “We don’t have a bipartisan energy policy in the US, which is very bad for the industry and our economy.” Ørsted, the world’s largest offshore wind company, has had to raise an extra $9 billion from investors after Trump’s hostility to the offshore wind sector prevented it from selling a stake in one of its major US projects. His tariffs on products from China mean higher costs for solar projects. Analysts say more large-scale solar projects are likely to have their permits revoked or reviewed. Developers are currently rushing to build as they have until July 2026 to start construction to capture the tail-end of the tax credits. But some projects and companies are bound to fail. “We’re likely facing several more years of uphill battles for many large-scale projects,” says Abby Watson, president at Groundwire Group, a consultancy. The IEA has halved its forecast for renewables growth by 2030 in the US to around 250GW as a result of Trump’s policies. Analysts at Carbon Brief estimate the country will emit 7 billion tonnes more CO₂ equivalent by 2030 under Trump’s policies than if the country had met its obligations under the 2015 Paris agreement, which he is withdrawing from. The reduction in renewables growth comes as the country’s electricity demand is rising due to the growth of data centres, many of which are looking to gas-fired or nuclear power stations because they need constant, steady power. Gas turbine makers are struggling to keep up with demand, while new nuclear power plants are often delayed. Retail electricity prices have already risen by 5 percent since July, according to the Energy Information Administration, and some experts caution they could rise further if supplies are constrained. “The writing is on the wall,” says Pol Lezcano, director of energy and renewables at the CBRE real estate group. Supporters of renewable electricity argue that the US is missing out on a revolution in cleaner, cheaper technology sweeping the world, with some likening it to the ageing cars on Cuba’s roads. But the relationship between renewable generation and consumer energy bills is complicated. The free energy from the sun or the wind means that the wholesale price of renewable-generated power is lower, but developers still need to make a return on their investment and grid operators may need to step in to ensure continuity of supply when the wind and the sun are low. “Even as the cost of producing electricity from renewables falls, consumers may not see immediate or proportional reductions in their bills, raising questions over the impact of renewables on power affordability,” the IEA said in its latest report. More broadly, the US’s focus on fossil fuels and pullback of support for clean energy further cedes influence over the future global energy system to China. The US is trying to tie its trading partners into fossil fuels, pressing the EU to buy $750 billion of American oil, natural gas and nuclear technologies during his presidency as part of a trade deal, scuppering an initiative to begin decarbonising world shipping and pressuring others to reduce their reliance on Chinese technology. But the collapsing cost of solar panels in particular has spoken for itself in many parts of the world. Experts caution that the US’s attacks on renewables could cause lasting damage to its competitiveness against China, even if an administration more favourable to renewables were to follow Trump’s. “China has run far away in terms of competitiveness,” says Antonio Cammisecra, chief executive of ContourGlobal, an independent power producer. “The US is capable of rebuilding, but it will take time.” Additional reporting by Ahmed Al Omran and David Pilling. Data visualisation by Jana Tauschinski. © 2025 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved Not to be redistributed, copied, or modified in any way.