Copyright Scientific American

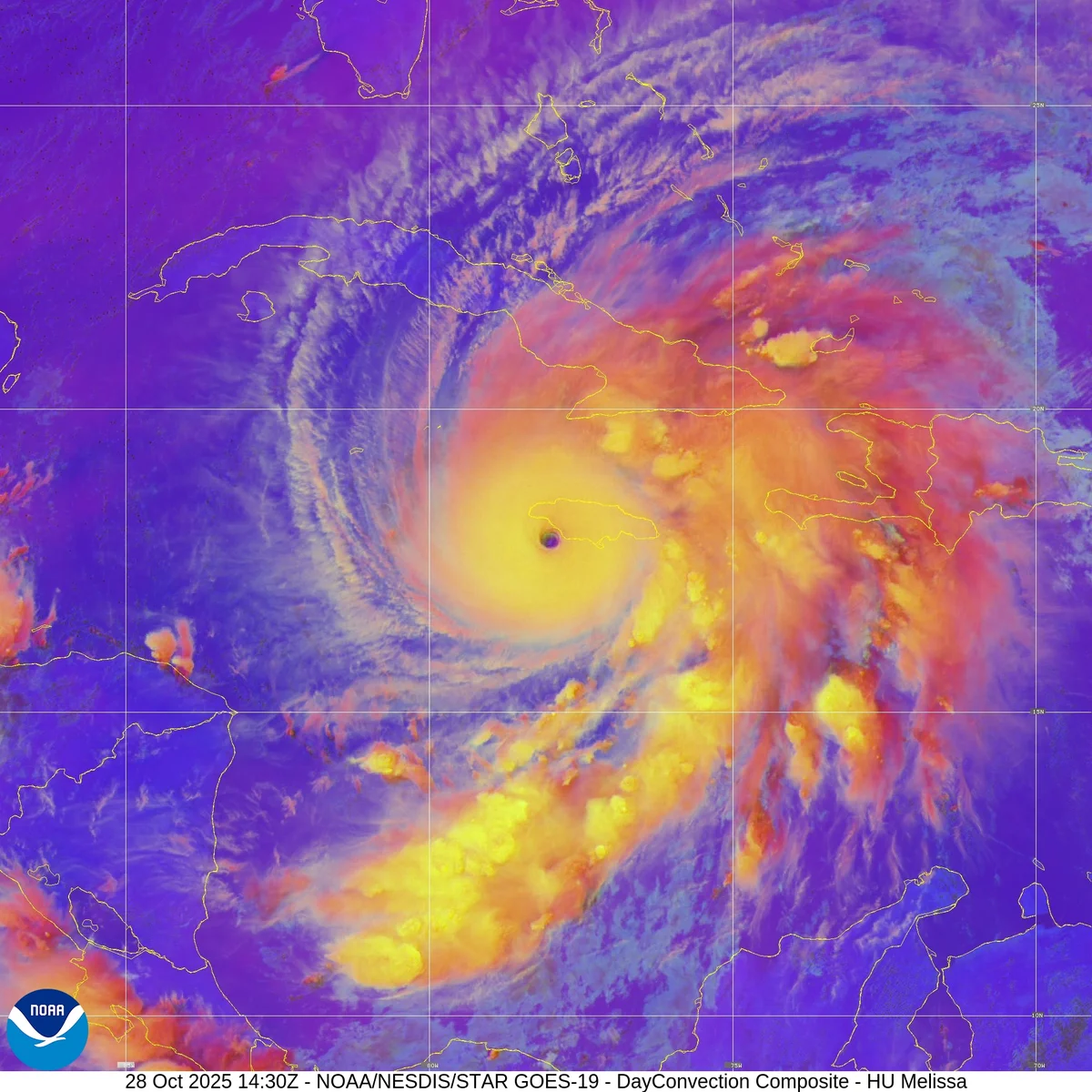

On October 28, Hurricane Melissa became one of the strongest hurricanes ever known in the Atlantic Ocean. The Category 5 hurricane has winds of 185 mph and a central pressure of 892 millibars, placing it in a tie with the 1935 Labor Day hurricane as the third most intense storm ever measured in the Atlantic. The 1935 storm wreaked massive devastation and wiped out the Florida Keys. “This is about as strong as hurricanes get,” says Brian McNoldy, a hurricane researcher at the University of Miami. Even in the Western Pacific, where powerful storms happen more frequently, few tropical cyclones would achieve this intensity. The reason Melissa has been able to reach this rarified company is a near-perfect alignment of circumstances. “This is taking advantage of every possible condition it can right now,” McNoldy says. On supporting science journalism If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today. “It’s this frustrating combination of—scientifically speaking—we know this is possible, but as humans we are flabbergasted at seeing manifest in this way,” says Kim Wood, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Arizona. The engine at the heart of any tropical cyclone is the convection powered by the temperature difference between the warm sea surface and the cold atmosphere at the top of the storm where air flows out. That outflow emerges at a layer called the tropopause, which marks the boundary between the troposphere (where Earth’s weather happens) and the overlying stratosphere. The tropopause is higher in the tropics than it is in more temperate latitudes. It’s also higher over the Pacific than the tropical Atlantic, which is part of the reason the Pacific’s typhoons are often stronger than Atlantic hurricanes (though they are the same phenomenon). Melissa is making full use of that tropopause height and its extremely cold cloud tops, fueling its exceptional convection. READ MORE: Hurricane Science Has a Lot of Jargon—Here’s What It All Means At the bottom end of its convective engine, Melissa has been parked “basically over the warmest water the Atlantic has to offer right now,” McNoldy says. Ocean temperatures in the Caribbean are at their peak in October after the summer months where “the ocean just sits and cooks,” he adds. Buoy measurements from a week ago showed water temperatures of 30 degrees Celsius (86 degrees Fahrenheit) or more down to 60 meters (nearly 200 feet). “There was a widespread bath sitting underneath what eventually became Melissa,” Wood says. Normally, a storm as slow-moving as Melissa has been—with forward motion of 3 to 5 mph—would churn up colder waters from deeper in the ocean, ultimately weakening the storm. But there is ample warmth deep enough in this area that that hasn’t happened to Melissa. “It’s pretty much the perfect place for this to happen,” McNoldy says. On the other hand, if Melissa had been faster-moving, it might not have been able to feed on the warm waters for as long. Yet this hurricane has barely moved in the past week. The time the hurricane has spent over this wealth of warmth has also helped it maintain its incredible intensity for so long—it’s been a Category 5 storm for more than a day. Melissa grew from a tropical storm to a major hurricane in a process known as rapid intensification, which occurs when a storm’s winds jump by at least 35 mph in 24 hours. Melissa’s winds increased by twice that amount during its first period of rapid intensification. “That’s extraordinary,” McNoldy says. Perhaps even more astounding was that it underwent another period of rapid intensification after it was already a Category 4 hurricane. And it has not only maintained its Category 5 status as it has slowly approached Jamaica, but has kept intensifying. Normally, as storms begin to interact with land—particularly with hilly terrain such as Jamaica has—friction starts to disrupt and weaken them. But Hurricane Melissa “looks like it doesn’t even know Jamaica is there,” McNoldy says. “It looks completely undisturbed.” It is clear that with a changing climate, ocean temperatures are rising and there is more moisture available to tropical systems. And there is a clear trend toward more—and more intense—rapid intensification and having a higher proportion of storms reach higher intensities. But whether we will see more situations of conditions lining up perfectly to let hurricanes reach their maximum potential is unclear, Wood says. But Melissa will likely spur much more research into that question.