Copyright National Geographic

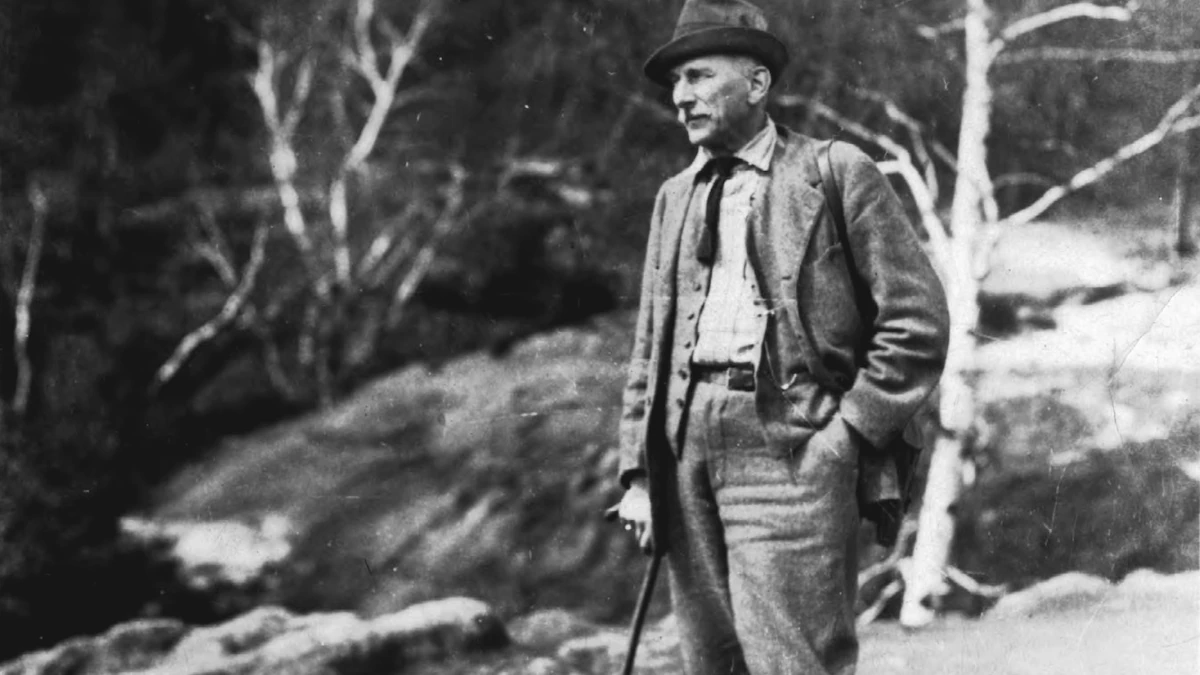

On a spring day in 1945, Christoph Rhoeneck perched at the edge of his family’s balcony. From the top floor of the brown, wood-clad house, in the middle of the southwest German mountain town of Lindenfels, he watched American tanks rolling up the valley below. Rhoeneck, at the time around five years old, watched the United States Army knock down fences and drive over his neighbors’ gardens, convoying along the village’s medieval road to the town center. Now 85 years old, he remembers thinking, “That’s awesome.” Lindenfels had expected Allied forces, and the machinery of war had been encroaching toward them—the city of Darmstadt, to the north, had been the subject of air raids by the Royal Air Force. Rhoeneck remembers the Odenwald forest that encircles the town being backlit by the orange glow of explosions and fire from the nearby city of Mannheim. The residents in Lindenfels, though, had a trusted cultural translator. Carl Alwin Schenck, an imposingly tall man in his mid-70s who had spent close to two decades in the United States before returning to his native Germany in 1913, told the town’s young boys to spread his order: “Go home. Go to bed. Americans are afraid of diseases. If you lie in bed and look sick, then you’re safe.” As Allied tanks arrived in town, Rhoeneck and his family took Schenck’s advice and jumped into bed—presumably, so did his neighbors. And as the Americans arrived in the middle of the town, Schenck went out to meet them in the town center, halfway between the cathedral and the castle. The Americans were surprised to a confident old man who spoke English, who welcomed them back to his house for a meal. LIMITED TIME OFFER Schenck’s familial roots ran deep in Germany’s Odenwald forest, but his life’s work is most visible to this day in the U.S. where his work is still evident across America’s landscape, particularly the Pisgah National Forest in the Appalachian Mountains of western North Carolina. A trained forester—born into a family lineage of woodsmen—he worked at the end of the 19th century, embodying an era of transformed American environmental policy, during which German-style “scientific forestry” spread across the country, forever altering the country's landscape. Schenck’s story is often forgotten in official histories of American forestry, but it’s worth retelling—his legacy is evident in the mandate of America’s National Forests, and in the footsteps of foresters in the woods. Coming to America At the age of 27, Schenck disembarked a ship from Europe and stood on American soil for the first time, in Hoboken, New Jersey. On that spring day in 1895, he was greeted by one of the most important figures in American environmental history: Gifford Pinchot, who would eventually become the first head of the United States Forest Service. Six months earlier, Gilded Age baron George Washington Vanderbilt II hired Schenck to manage the forests on his estate in Asheville, North Carolina. Built in the late 19th century, Biltmore Estate, was (and is) the largest private residence in America. It originally sat on 125,000 acres that left the famed landscape architect, Frederick Law Olmsted, unimpressed. As Olmsted designed Biltmore’s gardens, he recommended that Vanderbilt develop part of the grounds into a commercial forest. Vanderbilt envisioned Biltmore as a self-sustaining project—his vision aligned with German “scientific forestry” methods. These methods were developed in the shadow of over-harvest in Germany throughout the 18th century. A scarcity of wood forced immigration to North America, and private landowners started hiring trained foresters to ensure their land would be “productive” consistently. This led to scientific forestry—a strategic planting and harvesting of trees. That mode of conservation and management that stretches across the U.S today. It transforms forests into multiple use space that can be use for growing timber but also recreation, education, and small-scale harvest. And it was particularly important to private landowners like Vanderbilt who wanted to ensure that their land was profitable. Vanderbilt sent a telegram to Schenck: “are you willing to come to America and to take charge of my forestry interest in western North Carolina? -- George. W. Vanderbilt.” Schenck said yes. After arriving at the port, Pinchot and Schenck toured New York City, visiting the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH). At the AMNH, Schenck peered in awe at the massive slabs of redwood crosscut—circles of the trunk demonstrating the tree’s width and showcasing the grain and rings of America’s largest felled old-growth, preserved in the museum’s halls. In a haze of Gilded Age glitz, he boarded a train for Biltmore, unsure what he would find there. The grounds at Biltmore left Schenck underwhelmed. In his memoir, he recalls arriving in North Carolina: “Biltmore was nothing.” The forests around him had been logged, then left to regrow on their own, rather than with a management plan in mind. “From the German viewpoint,” he wrote, “the forest might be designated a chaos of trees.” Beech trees, oaks, and chestnuts were interplanted; pine and cedar grew alongside hickory. From Schenck’s perspective, this made it inefficient to harvest and sell Biltmore’s wood. An understory bloomed: rhododendron, ferns, and other low-height plants took up space that could otherwise be cleared for planted trees and harvesting equipment. They were the first American species that he had seen in the wild. Transforming Biltmore Schenck studied silviculture under some of the most influential foresters in history, including Dietrich Brandis (the father of scientific forestry) and Bernard Fernow (who was the first trained forester in the U.S. and, eventually, the head of the USDA). The tenets of German forestry lay in control and expectation: strict management plans for where to plant trees and what to cut could yield consistent profits for 80 years or more. Trees were grown with enough distance between them that horses could be ridden by foresters on their rounds. They also believed in the power of private landowners—as opposed to government—management. Still, Schenck found that his training in Germany’s forests had left him unprepared for the terrain, weather (Schenck often wore a tall felt hat), and social context of southern Appalachia. In Germany, public sentiment had shifted toward managing forests for long-term harvest. Many of these forests were meticulously plotted, with long straight rows of monoculture trees, which could be relied upon to grow uniformly to ensure consistent supply and revenue. They were efficient to manage—swift to log and situated well to take those logs to market—though ecologically sparse. This was a strong contrast to what he encountered on the grounds of Biltmore. Schenck wrote eloquently about encountering the “primeval” wood on the estate. To develop the forest around the mansion, he put into place methods that were a compromise of German ideas and American species. He introduced more coniferous trees and undertook experiments in planting acorns and oaks. Schenck, who liked to say that “the best forestry is the forestry that pays the best,” cleared the undergrowth and got rid of “mixed” plots of timber. He invented a ruler, for example, dubbed “the Biltmore Stick,” that helps land managers determine how much lumber a tree will yield when cut, and which is still in regular use today. Schenck’s view of forestry put him at odds with Pinchot. After leaving New York behind, the pair forged a fiery atmosphere at Biltmore that included accusations and altercations over how forests should be managed. Schenck had to follow through with plans that Pinchot had set forth that he disagreed with—like logging more trees than he wanted, and damming rivers to transport logs. Resistance to change at Biltmore, little direct oversight from Pinchot, and challenges in assigning staff meant that Schenck’s frustration built. Loggers hired by the estate often refused to work with a foreigner, and Schenck found resistance to his plans from Vanderbilt, too. The billionaire’s commitment to the estate earning profit quickly meant that sometimes Schenck was required to clear cut land that he didn’t want to. Still, Schenck persisted, using Vanderbilt’s fortune to get the forest up to working order. By the 1900s, Schenck’s work was so advanced that it took the form of a full curriculum, with textbooks, lecturers and a campus with cabins. He opened the Biltmore Forest School, the country’s first forestry school. The Biltmore School placed students deep in the woods rather than in a classroom. This would eventually become yet another place where Schneck and Pinchot’s would clash: at Yale, Pinchot relied heavily on classroom learning (forest education was so new in North America that students were required to read German forestry textbooks.) Meanwhile, Pinchot had started working in the federal government’s Division of Forestry where he preferred Yale graduates to staff his department, rather than Schenck’s students. The German stewed with anger. In 1903, Pinchot wrote to Vanderbilt, asking him to dissolve the Biltmore Forest School entirely. Vanderbilt declined. Eventually, though, the school was sold as part of 86,700 acres of land that would become the Pisgah National Forest, in North Carolina. The Pisgah is now dubbed “the cradle of forestry in America,” because of Schenck’s school. Eventually Vanderbilt soured on Schenck, firing him in 1909. The tensions between Schenck and the estate mounted (at one point, Schenck punched a man who accused him of lying about his budget) and his private management model proved too expensive, even for the Vanderbilt fortune, as economic crisis and financial crashes caused the price of lumber to plummet. Schneck returned to Germany in 1913. He fought for Germany in the First World War, and was shot and briefly held in a Russian prisoner of war camp. In the interwar years, he returned to forestry, hosting students from the U.S. who undertook cross-Atlantic field trips into German forests. (These mansion museums reveal the grittier side of the Gilded Age) Rhoeneck spent his childhood up the hill at Schenck’s house. The town’s school had deteriorated, and its administration fell into disarray. Schenck, keeping quiet and away from the German government, instead welcomed what he dubbed the “Schenck Boys” into his house every day at 10 o’clock. In rooms clad with wood plates, he read them bilingual editions of Hamlet, Macbeth, and Shakespeare’s sonnets, and assigned them what Rhoeneck described as “cruel and brutal” poetry. When the Schenck Boys weren’t reading classic literature, they spent afternoons in the woods where they learned about vegetation and wildlife, a stark contrast to the war raging around them. Schenck was too old to enlist by the time the Second World War broke out, and in all accounts wanted to quietly keep his head down in Lindenfels. As Schenck may have expected, though, wood was an invaluable element of war and, in post-war Europe was about to become an even more valuable commodity. Throughout the war, Allied forces had been meeting their wood needs by indiscriminately cutting down Germany’s forests. But as the end of the war drew near, both the Allies and Germany understood that good forest management would was necessary to not only rebuild Europe but to keep it warm. In March 1945, a group of American forces were poised along the west bank of the Rhine River, waiting to cross. In a personal essay, Edward Stuart Jr., an American forester who served in Company C, describes meeting forstmeisters in the woods while on their watch. Stuart asked one if he knew of Carl Schenck and if so, where might he be staying? If Schenck had survived the war, he was told, he’d be living in Lindenfels. Stuart crossed the Rhine with his troops, then boarded a Jeep with his company clerk, speeding right toward Lindenfels. “Lindenfels had survived with relatively little damage,” he wrote. “After a short search and within hearing of small arms and artillery firing, we located Dr. Schenck’s home.” Schenck lived in a wood-beam house built entirely from American tree species. Stuart knocked on the door cautiously. Schenck, aged but still tall, opened the door, and according to Stuart seemed relieved. “When he learned that I was also a forester, his welcome was unbelievably warm.” Stuart spent the afternoon with Schenck, and as he left, he put rations on the table. He then went to a nearby American military police unit and asked them to place Schenck’s house under protection while the region was still an active combat zone. “The side trip to ‘liberate’ Schenck had been well worth the risks taken.” When the war ended, Stuart’s military role turned into one of logging. He was designated a “military government forester,” and remained in Darmstadt. “As it turned out, this acquaintance would greatly assist the military,” he said. In the American zone of occupation, a forestry program was established, staffed by a handful of men who worked the woods back home. Stuart visited Lindenfels once a week throughout the summer months, to go “tramping” through the woods with Schenck. “Ever the teacher,” he noted, “Dr. Schenck indoctrinated me in the silvicultural aspects of German forests.” In September 1945, the forestry program was ordered to reestablish the German forest industry so that it could meet requirements for lumber, mine props, and firewood. Much of this wood would go to the U.S. Army. Allied countries in Europe received German forest products to help rebuild. Wood would go toward building prisoner-of-war camps and prisons. Lowest on the list of priorities was wood for firewood and to rebuild German homes. The result was mayhem. Many German forstmeisters were caught breaking the law and providing locals with wood for heat. Rationing was instated to gain control. A black market for wood appeared: one man was caught driving firewood over the border into France -- he had forged an agreement to exchange wood for wine. Former Nazis and members of the Communist party did what they could to disobey military orders and disrupt rebuilding efforts. Schenck eventually took on a lead role in administrating the forest--the man between Germany and America, again. The American troops stationed in the region for post-war recovery wanted to expedite forest nurseries, which in turn would lead to tree planting efforts that would produce wood and lumber on a relatively quick timeline. Stuart set up an office, employing Schenck. But Schenck’s difficult personality may have doomed the relationship, too. Rhoeneck remembers a falling out between Stuart and Schenck over the restoration of a bridge over the Rhine—Schenck slapped Stuart in the face, according to Rhoeneck’s memory. (Remains of a secret Arctic Nazi base reveal a forgotten chapter of WWII) Schneck’s lasting imprint on the American landscape A symbol of American bounty, forged into traditional German architecture, Schenck’s brown and white house still stands, a towering Douglas fir planted next to it stretching up beyond the roof. From the house’s perch, visitors cast their gaze over a cathedral and the remains of Burg Lindenfels, a castle dating back to 1080 AD. Their eyes hit two rare sights: a towering California redwood and several large Douglas firs, both native American trees rare in Germany. Schenck sourced these trees from nurseries and planted them himself. Two surviving sentinels to forest history and a largely forgotten figure. In 1951, Schenck stepped on American soil one last time. His return was notable enough to lead to a profile in the New Yorker, before he travelled as far west as Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park in the far north reaches of California, where a grove of redwoods was dedicated in his name. The Carl Schenck Grove stands off the park’s scenic Newton B. Drury Parkway, named for him by former students. He can also be found just outside Raleigh, North Carolina. There grows a 245-acre forest, rich with American beech, sycamore, black walnut, and the threatened species longleaf pine. The Schenck Forest is an outdoor laboratory. Here, students take on biology, entomology, mycology, crop science, and forestry. Here, they walk among trees among which Carl Alwin Schenck’s ashes have been scattered. Lyndsie Bourgon is a National Geographic Explorer, writer, oral historian, and assistant professor at the University of King's College. Her work has appeared in publications including the Atlantic, the New York Times and the Guardian. Her book Tree Thieves: Crime and Survival in North America's Woods, was published in 2022.