Copyright The New York Times

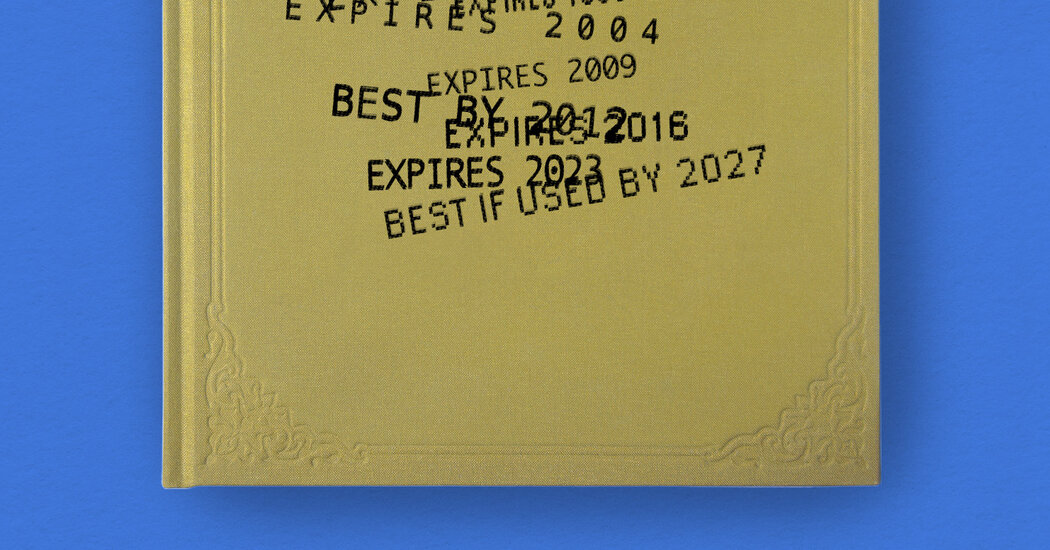

Critical discourse concerning the state of literature in general, and what we call literary fiction in particular, has ranged from the deeply pessimistic to the frankly apocalyptic. So many crises to weather, such an extreme falling off from a time when novels — serious, demanding novels — attracted widespread attention and respect. Substack essays and chin-pulling opinion articles galore agree that literature is not only in the doldrums, but even in danger of extinction from, take your pick, a declining attention span, a disappearing audience of people educated enough to understand and appreciate it, or a near-future technological onslaught (see: novels written by A.I. entities). The sense of a possible ending is palpable. But what the discourse leaves out are things like historical perspective and the blind faith and, from the purely practical and economic points of view, sheer illogic of the literary enterprise. Literature is fragile. It serves no obvious purpose. It does not feed us or clothe us or, unless you get very lucky, enrich us. But literature is also as close to immortal as any cultural endeavor of humankind has ever been. “The Iliad” or, even further back, “The Epic of Gilgamesh,” are both being read and drawn upon to create other works millenniums after their creation. William Carlos Williams captured this paradox beautifully: “It is difficult to get the news from poems / yet men die miserably every day / for lack of what is found there.” I am a terminal bookworm, and I am in no way inclined to shrug off the anxieties being aired. I even have some of my very own. But I also worked for 42 years as a book editor and published many books that answer to the description of literary fiction, and so I am inclined as well to take the long view on these matters. From my first day at work as a junior editor at a big paperback house in 1978 to the day I retired not long ago, the sky was always falling in respect to the financial viability of books of depth and ambition. The only difference from one year to the next was the perceived rate at which it was falling. In the late 1970s the big worries were that the rise of chain bookstores and the new corporate ownership of family-owned publishing houses would mean the end of quality books and a race to the best-selling bottom. Neither of these outcomes came to pass. With predictable regularity the word would come down from the corner offices to the editorial corridor that we were publishing too many “small” novels and needed to cut back. Sometimes we even did — for a while. I remember the vogue in the ’60s and ’70s for critical essays predicting the imminent “death of the novel.” In Wilfrid Sheed’s mordant portrait of the protagonist of “The Minor Novelist,” he writes, “He tries to keep away from Sunday supplements which discuss the death of the novel. He has a theory that it is bad luck to read more than three articles on this subject a week.” Legions of M.F.A. grads can relate. And yet, that wounded beast, the literary novel, keeps on being written, being published, and, when the fickle gods smile upon it, even bought and read, as the publishers of Colson Whitehead, Sally Rooney and Percival Everett, to name just three large talents, can attest. If literary fiction is a corpse, it’s a wonderfully animated one. What I am about to say on this matter may seem perverse, but I think a look back at the instances where great works of literature almost disappeared upon publication or came close to not being published can offer a useful perspective, and even a modicum of hope, that the game is far from over. “Moby-Dick,” the novel that is America’s clearest contribution to world literature, was so misunderstood and reviled upon its 1851 publication that it destroyed Herman Melville’s career. He had to take up work for the rest of his life as a customs inspector on the New York docks, and his obituary in this paper referred to “Mobie Dick.” It was only after his death and the novel’s rediscovery in the early 20th century that it was recognized for the masterpiece it is. In the mid-1940s every one of William Faulkner’s 20 published works was either out of print or very difficult to find. Faulkner had to grind out screenplays for Hollywood studios to make a living. It took an anthology edited by the critic Malcolm Cowley, “The Portable Faulkner,” to reverse years of neglect and critical abuse and finally get him the recognition (and the Nobel Prize) he deserved. Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road,” his culture-shaping novel of the quest for freedom and experience, was rejected by numerous New York publishers as scandalous and far too “out there” to be taken seriously. It took several years for the Viking Press to overcome its fears of libel and obscenity suits to publish it, whereupon it helped ignite the movement that came to be called the counterculture. (During this time, “Lolita” was being emphatically rejected for some of the same reasons by many of the same publishers.) Dawn Powell is today recognized as one of the wittiest and most worldly American novelists of the past century, but her career was one long exercise in commercial futility despite having some of the best editors and publishers — Maxwell Perkins and Scribner’s, for example — in her corner. She died in near poverty and relative obscurity, and it was only through the posthumous efforts of her friend Gore Vidal and the tireless Tim Page that her books have found the audience they always deserved. Sam Lipsyte’s hilarious 2004 novel “Home Land” takes the form of alumni notes from the hapless Lewis Miner, the most comprehensively failed graduate of his high school class; it can be said to have noticed (and maybe even created) the existence of the manosphere years before the word was coined. It was reportedly turned down by 35 publishers before finally being published as a paperback original, to widespread praise and belly laughs. Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel masterpiece “Maus” collected numerous rejections (including from me) before it was finally published. The life of literature and the lives of its creators are radically unpredictable and, frankly, fractal. As much as we would like to think that the republic of letters, as it used to be called, is a linear and orderly place where the best books are immediately recognized for their quality and achievement and therefore rise like cream to the top, the precise opposite is true. Publishers and editors are deeply fallible people (I know all about it), prone to errors of judgment and failures of nerve and blind spots of literary perception. The very greatest books can be published at the worst possible times for their greatness to be perceived. Just the wrong review in just the wrong place (or a slew of them) can consign a genuine masterpiece to (we may hope) temporary oblivion. Literary reputations are never static and fixed, instead being subject to a ceaseless churn as tastes change and evolve. In fact, the trend of the moment in literary publishing is backward-looking, as a clutch of new imprints scour dusty backlists and long out-of-print books for titles whose time has finally arrived. I in no way intend to make light of the structural and cultural headwinds that are making literary publishing a difficult and chancy enterprise. The grip of commercial blockbusters and genre novels on the best-seller lists is as depressing to me as it is to other commentators. Yet the dogged vitality of the habit of reading — evident in the passionate commitment of literary fiction’s fan — is a source of hope. Books are hardy specimens. The longest line I found myself in this past summer on Cape Cod — longer even than the one at the Snowy Owl coffee shop — was on the first day of the wildly popular book sale at the Brewster Ladies’ Library, which raises funds for the library. All of us on the checkout line, including many parents and their excited children, were carrying armfuls and shopping bags full of books of all descriptions. If literacy is dying, nobody has told my fellow enthusiasts on that line. The worst possible thing those of us who care about literature can do is sell it short and put some end date to it. The future is always being written at every moment, and hope and faith and even an irrational belief in literature’s primacy in and importance to the human prospect is the cure for despair. All of the books I mention in this essay survived to see fame and recognition and a kind of permanence against long odds. Henry James, who had some career setbacks of his own, put it best: “We work in the dark — we do what we can — we give what we have. Our doubt is our passion, and our passion is our task. The rest is the madness of art.” Or as the Mets pitcher Tug McGraw phrased it a bit more economically: “Ya gotta believe!”