Copyright Rolling Stone

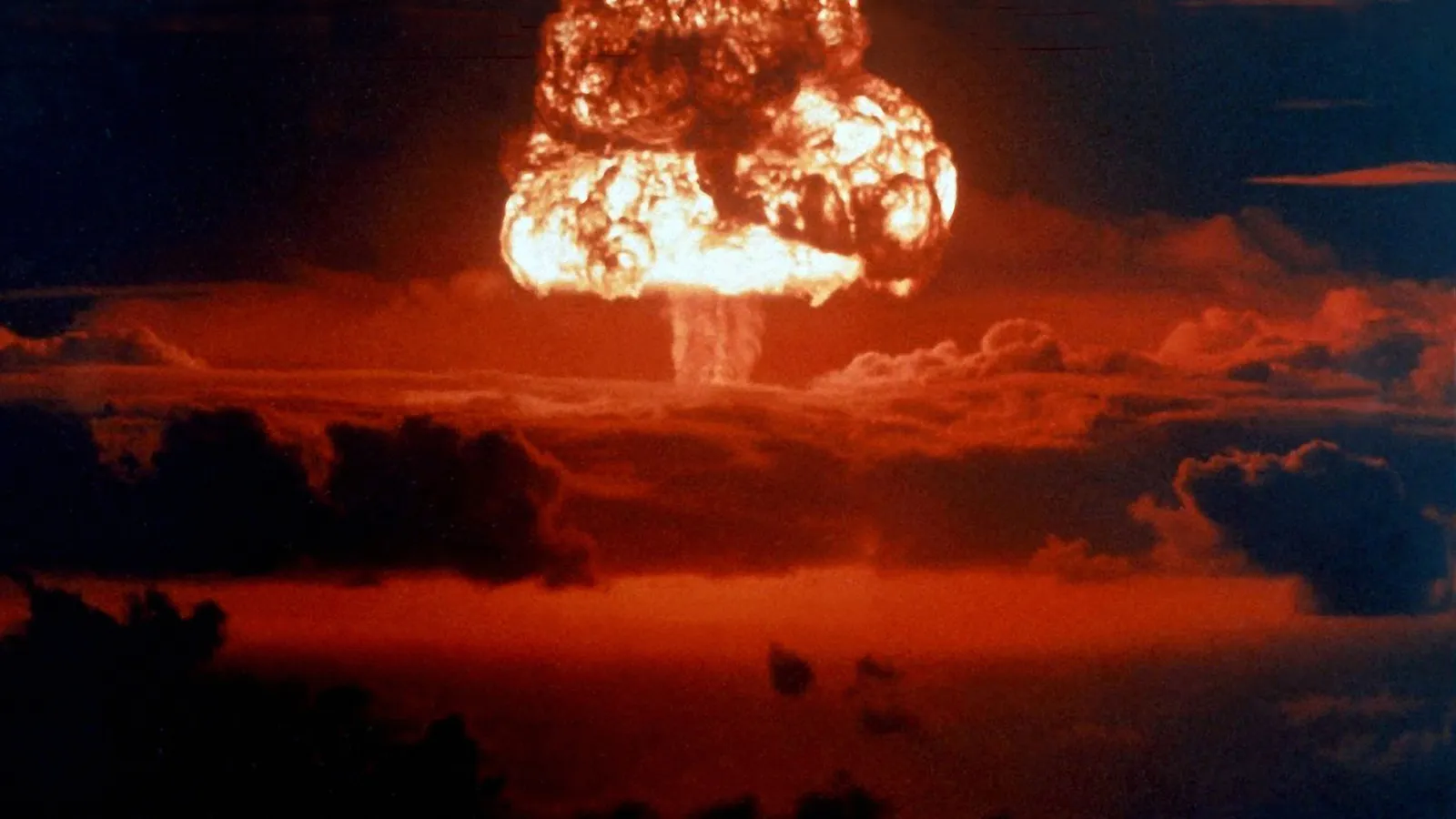

MAJURO, MARSHALL ISLANDS — Lemeyo Abon learned about snow from the movies played on projectors by visiting American sailors. But living on Rongelap — a remote tropical atoll in the central Pacific Ocean — she had never seen it. So when soft flakes began falling from the sky, the then 14-year-old girl and her friends were enchanted by the new experience. They excitedly began playing with the fluffy white material. But it wasn’t snowing. What was falling from the sky was highly radioactive pulverized coral ash, fallout from the largest nuclear explosion in history up to that date. Abon felt her eyes and her respiratory tract burning as she played with the ash. By evening, everyone on the island was critically ill. For years, the United States used the Marshall Islands, where Rongelap is located, as a testing ground for its nuclear program. The test on March 1, 1954 was called Castle Bravo, and it was 1,000 times more powerful than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. The detonation didn’t go as planned. The bomb was more powerful than scientists had expected. Test observers were surprised by the blast’s intensity, and rapid spread of fallout. They were forced to shelter in place in a protected bunker. Some 7,000 square miles of ocean would be contaminated. So were inhabited islands. The Marshallese living in surrounding atolls didn’t have protected bunkers. There was no warning to locals about the test, no mandatory evacuations in case something went wrong. In the days after Castle Bravo, residents of Rongelap were evacuated by the U.S. Navy, told they would be able to return home in a few weeks. “There’s a picture of my grandfather holding a baby as they wait to be evacuated from Rongelap,” Ariana Tibok, a member of the country’s National Nuclear Commission, tells Rolling Stone. “You can see the scabs that are already forming on their skin.” Within a week of the incident, the U.S. government began a secret program to evaluate the impact of radiation on the islanders. Twenty of the 29 children on Rongelap would later develop thyroid cancer. Editor’s picks A fierce advocate for nuclear survivors, Abon told her story for decades, providing testimony to the United Nations. She died in 2018, without ever returning home. More than 70 years later, and Rongelap — like three other atolls across the northern Marshalls: Bikini, Rongerik, and Eniwetok — is multigenerationally uninhabitable due to contamination from nuclear tests. Arms Race “Because of other countries’ testing programs, I have instructed the Department of War to start testing our Nuclear Weapons on an equal basis. That process will begin immediately,” President Donald Trump wrote in a post on social media on Oct. 29. The president’s declaration appears to have been provoked by advanced weapons tests conducted by Russia. Earlier in the day, President Vladimir Putin announced Russia had carried out successful tests of a torpedo called “Poseidon” and a cruise missile called “Storm Petrel.” Both can carry nuclear warheads, but that isn’t their distinguishing feature: They each use nuclear propulsion, enabling them to travel extremely long ranges. “Both of these systems are designed to defeat U.S. missile defenses,” says Dr. Jeffrey Lewis, an arms control specialist and professor of global security at Middlebury College. “They are ideas that date to the 1980s, when the Reagan administration was considering SDI [the Strategic Defense Initiative, also known as “Star Wars”]. They were revived in the early 2000s, when George W. Bush pulled out of the ABM [Anti-Ballistic Missile] treaty, and they remain relevant because they would be used to evade Golden Dome,” Trump’s planned missile defense program. Related Content In the wake of Trump’s statement, officials offered equivocations about the administration’s nuclear plans. Vice Admiral Richard Correll, Trump’s nominee to lead U.S. Strategic Command — which is in charge of America’s nuclear arsenal — appeared in a confirmation hearing before the Senate on Oct. 30. He dismissed speculation about explosive testing of warheads. “I believe the quote was, ‘start testing our nuclear weapons on an equal basis.’ Neither China or Russia has conducted a nuclear explosive test, so I’m not reading anything into it, or reading anything out. To my knowledge, the last explosive nuclear testing was by North Korea, or DPRK — and that was in 2017.” Most experts agree. “As best I can tell there have been no tests of warheads,” says Lewis. “These are just tests of delivery systems. The Russians ended explosive nuclear testing in the early 1990s, and signed the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty [CTBT].” Nevertheless, in an episode of 60 Minutes on Nov. 2, Norah O’Donnell asked Trump to clarify whether the U.S. was going “to start detonating nuclear weapons for testing?” Trump replied: “I’m saying that we’re going to test nuclear weapons like other countries do, yes.” “Russia’s testing, and China’s testing, but they don’t talk about it,” Trump later insisted, adding: “We’re gonna test, because they test and others test.” Trump may have been referring to subcritical testing, in which small amounts of nuclear material are subjected to explosives without generating a nuclear chain reaction. The purpose is to assess the “safety, security, reliability, and effectiveness of America’s nuclear warheads, without the use of nuclear explosive testing.” All major nuclear powers conduct such tests — the U.S. completed a series of such experiments in July. What, then, does “equal basis” mean? Experts say if there is evidence Russia and China are conducting something other than subcritical testing, it hasn’t been made public. Lewis points out that the U.S. also regularly conducts tests of its nuclear delivery systems, including land-based and submarine-launched ballistic and cruise missiles. Indeed, on Nov. 5, the Air Force fired a warhead-less LGM-30 Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missile, or ICBM, from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California, across the Pacific to the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site — on Kwajalein Atoll, in the Marshall Islands. Lt. Col. Karrie Wray, commander of the 576th Flight Test Squadron, said the test was designed “to verify and validate the ICBM system’s ability to perform its critical mission.” “The idea that we aren’t testing on an equal basis seems very strange to me,” Lewis says, “except in the sense that we don’t have exactly the same forces — so, we don’t have a nuclear-powered cruise missile. On the other hand, we don’t need a nuclear-powered cruise missile. The Russians don’t have an amazing air defense network that we need to evade in a circuitous route.” Apparently in response to Trump’s statements, Putin on Nov. 5 ordered officials to start preparing for a “possible” resumption of explosive nuclear tests. He said Russia had adhered to its obligations under the CTBT, but that if the United States or any nuclear power carried out a test, Russia would do so, too. Later that night the American president doubled down, again writing the U.S. would “start testing our Nuclear Weapons on an equal basis.” Experts are alarmed. “All of the rhetoric that’s been flying around about a potential return to testing is really disturbing,” says Dr. Emma Belcher, president of the Ploughshares Fund, a nonprofit that works to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons. “We do know that there are people inside the administration — and outside the administration — who want the United States to return to testing.” During Trump’s first term, administration officials awarded a contract to replace the Minuteman III with a new generation of ICBMs, the LG-35A Sentinel. The push to modernize America’s nuclear “ground-based deterrent” meshes with the collection of policy proposals written by the conservative Heritage Foundation, known as Project 2025. That proposal discusses the nation’s nuclear program dozens of times, saying the U.S. must “indicate a willingness to conduct nuclear tests in response to adversary nuclear developments if necessary.” It also advises the Trump administration to “restore readiness to test nuclear weapons at the Nevada National Security Site,” update nuclear forces “in light of China’s modernization breakout,” and pull out of the CTBT, which the U.S. signed, but never ratified. The U.S. is far ahead of its nuclear adversaries in research and data about nuclear warheads, and experts Rolling Stone interviewed for this article believe explosive testing is not only strategically unnecessary, but, as several put it, “insane.” They’re worried that the bulwark of cooperation intended to stave off nuclear disaster — nonproliferation treaties — is being dismantled, piece by piece. The U.S. has already withdrawn from two major agreements: The Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2002, and the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces Treaty in 2019. “On this issue, I really feel so strongly that it needs to be a bipartisan issue, that actually this should be the ultimate pro-life issue,” says Dr. Ivana Hughes, a chemistry professor at Columbia University who studies the impact of nuclear testing, and who is the president of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation. “It doesn’t get any more pro-life than preventing the annihilation of humanity and potentially all of life on the planet.” There are currently around 12,000 functional nuclear weapons worldwide. China is rapidly increasing its arsenal. In addition to the U.S. and Russia, other nuclear powers — like France and the U.K. — have ambitious plans to modernize theirs. “We made lots of progress after the end of the Cold War and brought those numbers down, but now the numbers have either stayed the same or are really increasing — like in the case of China,” Hughes says. She desperately hopes the nonproliferation regime can be salvaged, including New START, a nuclear arms reduction treaty between Russia and the U.S. that is set to expire in February 2026. Some Republicans hope to walk away from the accord. “New START was a one-sided agreement negotiated by Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, and extended by Joe Biden,” Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., posted on social media on Nov. 6. “It’s time to let it die its natural death and accelerate U.S. nuclear modernization.” Belcher, of Ploughshares, worries about the future of New START. “I actually have serious questions about whether the two sides can come to an agreement,” she says. “The main point here is that when we abandon diplomacy, we signal that both restraint and transparency are optional.” “The crumbling of the nonproliferation regime is really worrying, because treaties that create the regime have the architecture to address challenges and violations,” she adds. “And when there aren’t any treaties, the only solution you’ve got is the building and deploying of more weapons.” Lewis, the arms control expert, is not optimistic. “I used to say that it wasn’t a race, but that we are lacing up our tennis shoes. Now I think we’re jogging around the track and starting to accelerate,” he says. “This won’t happen all at once. It’s not a race in the sense that there will be a starting gun. The whole process will just kind of pick up momentum almost imperceptibly, until 10 years from now we’re all sitting in the midst of a really serious arms race, wondering: ‘How did we get here?’” ‘Gifts From God’ On a balmy weekday morning in Majuro, young children play fearlessly in the lagoon. Young boys commandeer sheets of wood from a pile of construction debris, and use them as makeshift rafts that they row with planks, kayak-style. The boys are probably 10 to 12 years old, and as they stroke in unison on alternate sides of their improvised craft, they sing cadence in their mother tongue. The scene is a miniature echo of the paintings of Marshallese warriors in traditional canoes, arms raised in unison mid-stroke, that grace the walls of a local hotel. The world has long forgotten the early Cold War’s nuclear tests. The Marshallese have not. The children aren’t in school because it is Nuclear Remembrance Day, a national holiday in the Marshall Islands. The collection of coral atolls, known historically by locals as jolet jen Anij – “Gifts from God” – were first settled by humans approximately 4,000 years ago. Starting in the 16th century, they changed hands between a series of imperial powers. The tiny atolls have little in the way of resources; their primary value for outsiders is their strategic location. By the outset of World War II, the Japanese controlled the Marshalls, key outposts in their chain of defenses intended to keep the U.S. at bay. In 1944, the U.S. Navy — at that point in the war a seasoned fighting force that had nearly perfected amphibious operations — reached the Marshalls, destroying the Japanese garrisons there. The battles killed more than 11,000 Japanese — and the forced laborers they had brought with them — with just over 600 Americans dying in the fighting. A year later, the war ended when America used its newly developed atomic weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. When peace came, Europe was divided between the Soviet Union and its former Allies, and the Cold War had begun. The United States, still the world’s only atomic power, wanted to demonstrate the awesome might of “The Bomb.” It looked to the Marshall Islands. President Harry S. Truman ordered the U.S. Navy to conduct an atomic test in 1946. The Soviets were invited to witness it. Dubbed Operation Crossroads, it was the first test since Trinity. The site chosen was Bikini Atoll, its massive lagoon filled with an armada of ships, allowing the military to study the effects of an atomic weapon on naval vessels. But there was a catch: Bikini was inhabited. So the Navy devised a plan to relocate the islanders, promising them they could later return. In truth, no one really knew the effects a nuclear test would have on the island. There’s archival film of U.S. Navy Commodore Ben H. Wyatt making the case to the Bikinians. Clad in his khaki service uniform, Wyatt sits on the trunk of a coconut palm, speaking through his interpreter: “Alright now James, will you tell them that the United States government now wants to attempt to turn this great destructive force into something good for mankind — and that these experiments here in Bikini are the first step in that direction.” The translator has a brief exchange with a man Wyatt calls “King Juda” — the Iroij, or paramount chief, of Bikini Atoll — who explains that his people understand and will agree to move, concluding simply: “Everything is in God’s hands.” Wyatt replies: “That’s fine… everything being in God’s hands, it must be good.” The narration captures the hopes of the Atomic Age — or at least, the government’s spin about nuclear testing: “Concealed within the fiery terror that is the atomic bomb, are hidden the broader and nobler aspects of its mystery — the power for good rather than for evil. The ability to save, not destroy mankind. To build him a whole new world of atomically powered peace. It is to this glorious opportunity that the humble Bikinians are contributing their little all. I wonder… would you so readily give up your everything?” Nuclear Sins Alson Kelen remembers his ancestral home as a paradise. A Bikinian born in exile, his parents were forced to leave ahead of Operation Crossroads. They were told they would soon return. It was 23 years later when Bikinians were first allowed to go back. Without human inhabitants, the atoll had become a cornucopia of fruit and fish. “You could walk out into the lagoon and just pick up fish in your arms,” Kelen tells a reporter for Rolling Stone. “You didn’t need fishing gear.” There is no word in Marshallese for “radiation.” The closest approximation is “poison.” When people talk about it, they simply use the loanword bomb or “baaṃ,” to describe radiation exposure. “King Juda,” who led his people into exile at the behest of the U.S. government, died of cancer in 1968, a year before his people started returning to the island. The homecoming was premature. “Although some radioactive contamination was still known to linger, it was believed at the time that restrictions on the consumption of certain native foods and provision of imported foods would make Bikini habitable,” the Department of Energy notes in its report on Human Radiation Experiments. “Unfortunately, these assumptions proved wrong.” Scientists monitoring Bikinians became increasingly alarmed at evidence of cumulating radiation exposure. The island was re-evacuated in 1978. “I can safely say that more than 95 percent of Bikinians, maybe even 97 percent of Bikinians, have never seen Bikini before,” says Kelen, who served as mayor-in-exile of the atoll from 2009 to 2011. To most, “it’s a myth.” “We don’t want anybody else to go through what we went through. ‘For the good of mankind’ this happened, to bring peace to the world,” he says. “That journey to bring peace to the world is still there, but we sacrificed everything for it.” In 1986, the U.S. ratified a “Compact of Free Association,” or CFA, governing its relationship with the Marshall Islands. Washington effectively subsidizes the Marshallese government in exchange for military access — the most recent update of the CFA provides $700 million over four years. The original CFA included a clause promising “a just and adequate settlement” to those harmed by nuclear testing. A $150 million trust fund was established to pay compensation. The independent tribunal adjudicating claims eventually awarded over $2 billion in damages. By 2000, it was clear the fund was insufficient to meet demand; most claims are unpaid. The tribunal effectively ceased operation in 2011; requests by Marshallese for the U.S. to replenish the nuclear compensation fund have been ignored. Washington is rarely interested in having to pay for its sins, whether nuclear or otherwise. Mary Dickson, who lived in Utah in 1962, blames the nuclear testing conducted in nearby Nevada for its lifelong impact on her health. She has worked for years trying to prove that her neighborhood, ensconced in a canyon near Salt Lake City, was particularly hard-hit from radiation exposure. “We had no idea all that time what was working its way through our bodies. Sometimes it takes decades for the cancers to show up after exposure,” she says. “I was in my 20s when I was diagnosed with thyroid cancer.” Dickson is a “downwinder,” the term used to describe people exposed to radiation from atmospheric nuclear tests due to prevailing winds depositing dangerous levels of fallout. “The government never did a very good job of tracking it, of monitoring it,” Dickson says. “The vast majority of people who were affected will never know they were. They won’t know that’s what made them sick.” Throughout the Cold War, the U.S. continued conducting tests in the Pacific, and also on its own soil — in Nevada, where there were 100 atmospheric tests and some 800 underground tests, as well as in Alaska, where there were a series of underground tests. In total, the U.S. detonated 1,054 nuclear weapons between 1945 and 1992. All of the world’s nuclear powers combined have detonated some 2,000 nuclear weapons since 1945. The radioactive fallout from these tests has spread across the globe. Atmospheric testing, in particular, “caused the largest collective dose from man-made sources of radiation” in recorded history, researchers say. Radionuclides — unstable elements that release radiation as they decay — from the tests will continue to spew their doses into the environment for centuries to come. With sufficient accumulation, radiation exposure can increase an individual’s risk of multiple types of cancer. As data accumulates, understanding of the broader impact of testing is evolving — but there’s obvious evidence people closest to the tests were the most affected. A decades-long effort to get the U.S. government to acknowledge this resulted in the passage of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, or RECA, in 1990. The government has now paid out over $2.6 billion to more than 41,000 claimants in a dozen states since RECA was first passed. Dickson was part of an effort to update and expand RECA, which passed earlier this year with bipartisan support in Congress. The expansion acknowledged that communities as far away as Missouri — where waste from the Manhattan Project was stored — had been affected by nuclear tests. Nevertheless, Dickson notes, ultimately the burden of proof is on the individual, who must seek out decades-old medical records and proof of residence — in her case, from when she was a child — to file a successful claim. “How unconscionable is it to even think about testing those weapons again, when we know the damage that they cause? We know there are real people who were harmed by those tests,” Dickson says. “And I hate to call them tests. They are actual detonations of nuclear weapons.” Trending Stories Many questions remain about Trump’s nuclear intentions. But the most fundamental question may be: Is explosive testing worth the cost? Perhaps the answer can be found on Bikini Atoll.