Copyright forbes

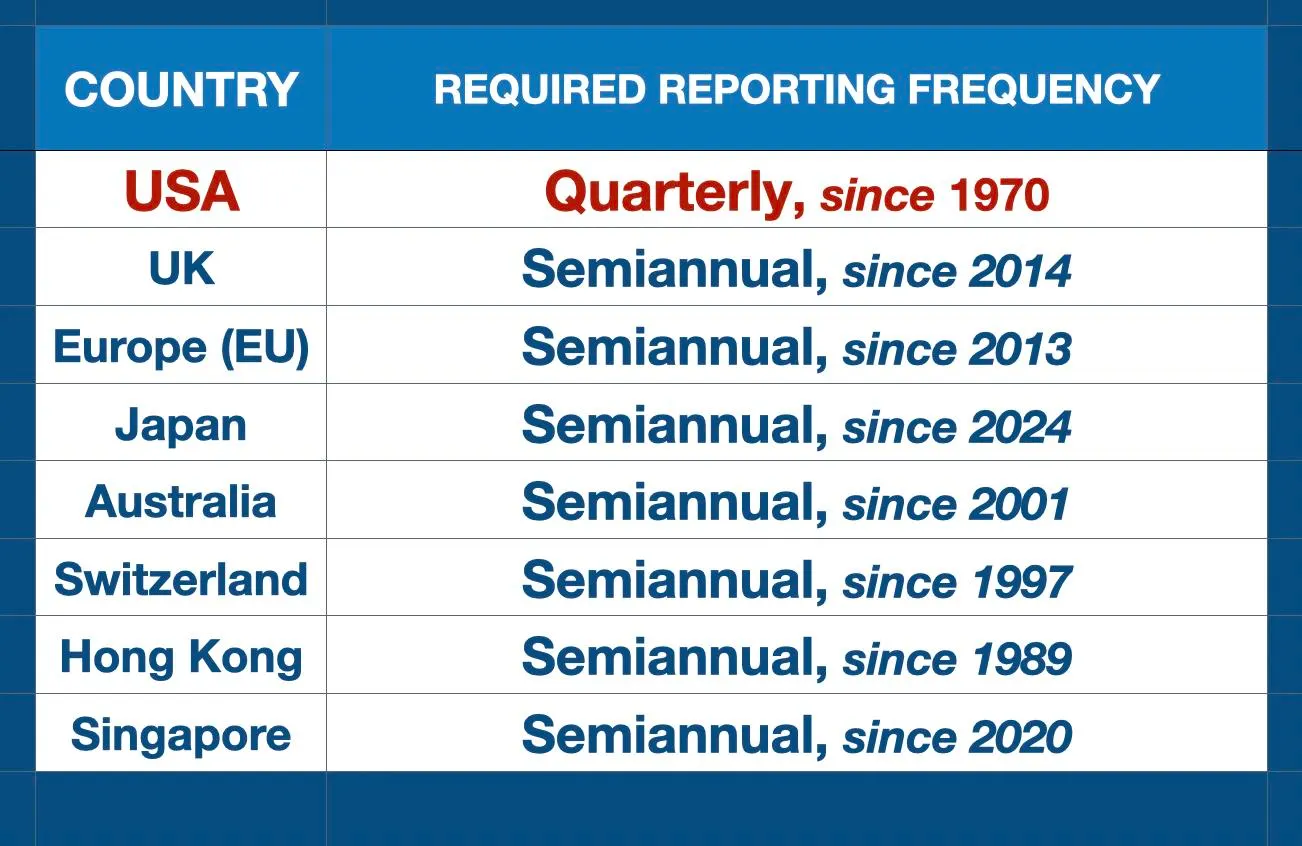

U.S. financial regulators will soon modify or rescind the 55-year old rule requiring public companies to issue formal financial reports every 90 days. Surveys of business leaders consistently reveal concerns about the cost and distraction of preparing and managing the short-cycle reporting process. They also provide evidence of a short-term bias in corporate decision-making, linked to the pressures of the current quarterly reporting cycle. There is an acknowledged tendency to sacrifice long-term strategic investments, alter accounting schedules, and incur other financial penalties (e.g., customer discounts for favorable purchase arrangements) in order to meet quarterly earnings targets. Meanwhile, academic and industry studies indicate that semiannual reporting does not impair, and may even improve, company performance, the functioning of financial markets, and the quality of financial information available to investors. Finally, the quarterly reporting regime has created a significant short-term disruption or distortion of trading patterns centered around the earnings announcement – dubbed the “Earnings Game” – characterized by abnormal volatility, evidence of mispricing and market anomalies or inefficiencies, an open door to market manipulation, and disadvantages for small investors in particular. In this Part 1, we will review the “big picture” arguments pro and con. In Part 2, the focus will be on the nature and consequences of the Earnings Game. The United States stands alone (almost) among advanced economies in requiring quarterly financial reports from all public companies. Comparison of Required Reporting Frequencies in Various Countries* Chart by author The Securities and Exchange Commission enacted the quarterly reporting requirement in 1970. It has evolved into a highly structured, closely regulated framework which defines how companies communicate with the financial markets. MORE FOR YOU Other countries have experimented with the American model – and then abandoned it. The European Union mandated quarterly reporting in 2004, but rescinded the rule in 2013. British regulators instituted a quarterly reporting requirement in 2007 – and repealed it seven years later. Singapore was quarterly for 17 years until 2020. Japan’s experiment with full quarterly reporting ran from 2003 to 2024. (Only Canada still follows the American example.) The SEC has now indicated that it wants to eliminate the quarterly reporting requirement in favor of semiannual reports by late next year, with full implementation expected by 2028. It is of course controversial. The arguments both for and against the proposed change tend to focus on how reporting frequency might influence the way companies are managed or the way markets function. Both sides often rely on deductions from “theory,” or simple appeals to “obviousness” – rather than hard evidence, which is scarce (for reasons discussed below). In the following sections, we’ll state the case for each side and review the available evidence. The Case For Eliminating Quarterly Reporting The main argument for change is the claim that quarterly reporting encourages “short-termism” – a tendency for companies to sacrifice long-term growth and investment in favor of short-term measures aimed at boosting quarterly results. This was the rationale for ending mandatory quarterly reporting in the EU. “[Quarterly reporting requirements] encourage short-term performance and discourage long-term investment. In order to encourage sustainable value creation and long- term oriented investment strategy, it is essential to reduce short-term pressure on issuers and give investors an incentive to adopt a longer term vision.” - The EU’s October 2013 “Transparency Directive” The EU even sees a “problem” with companies that continue to issue quarterly reports voluntarily. Regulators are said to be considering “more draconian measures, including ways to discourage or ban listed companies from reporting on a quarterly basis” even when they are not required to do so. UK regulators followed the recommendations of the Kay Report (authored by the prominent economist John Kay), which defined short-termism as “a tendency to under-investment, whether in physical assets or in intangibles such as product development, employee skills and reputation with customers” and sought ways to “reduce the pressures for short-term decision making that arise from excessively frequent reporting of financial and investment performance (including quarterly reporting by companies).” American critics of “quarterly capitalism” have included Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton (who coined the phrase), and Joe Biden, who wrote in 2016 that – “Short-termism—the notion that companies forgo long-run investment to boost near-term stock price—is one of the greatest threats to America’s enduring prosperity….The origins of short-termism are rooted in…a financial culture focused on quarterly earnings.” Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JP Morgan, and Warren Buffett have criticized the “short-termism that is harming the economy” driven by an “unhealthy focus on quarterly earnings.” Larry Fink, the CEO of BlackRock, blames “today’s culture of quarterly earnings hysteria” which is “totally contrary to the long-term approach we need.” David Solomon, CEO of Goldman Sachs, believes investors “can get adequate financial disclosure in two reporting cycles and it frees up both time and economic opportunity to really focus on the business and take a longer term view.” Norway abolished quarterly reporting in that country in 2017, and the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund ($1.8 Tn) has proposed eliminating quarterly reporting for all public companies everywhere, citing the “risk of companies prioritizing short-term profits and the meeting of analyst forecasts over long-term investment, value creation and sustainable development.” “Regular semi-annual reporting, supplemented with continuous updates of material information, should adequately meet disclosure requirements. Short termism can undermine the benefits of being publicly listed, and discourage companies with longer-term strategies from going or remaining public.” The former Chairman of Temasek, the Singapore sovereign wealth fund, cited the problem of short-termism among investors: “Issuing three-monthly updates on corporate performance does not improve transparency but does encourage investors to take a damagingly short-term view of their equity holding.” The President of the New York Stock Exchange focused her comments on the “burdensome” cost of preparing and managing short-cycle financial reporting. “The rigidity around reporting has become onerous…the quarterly earnings calls, the prep work, the roadshows, the disclosures upon disclosures. Simplifying some of those requirements would certainly lessen the cost.” – Fortune (Oct 2025) So, too, Nasdaq – “Nasdaq is a strong supporter of reforms that would give companies the option to report either quarterly or semi-annually. By minimizing the friction, burden, and costs associated with being a public company we can further invigorate the U.S. capital markets, unlock new job creation, and accelerate the growth of our economy.” Many leaders of nonfinancial firms believe that eliminating this short-term bias would improve business operations. Unilever’s CEO said that after the company stopped issuing quarterly reports – “Better decisions are now being made. We don’t have discussions about whether to postpone the launch of a brand by a month or two or not to invest capital, even if investing is the right thing to do, because of quarterly commitments.” The Vice-Chairman of General Motors concurred: “The search for quarterly earnings is the father of many, many bad product decisions.” In sum, advocates of less frequent reporting argue that the current quarterly cycle tends to distort business decision-making, and thereby harms investors. It may even constitute a “threat to America’s enduring prosperity” (to again quote former President Biden). In Favor of the Status Quo Traditionalists in the financial establishment generally line up against the proposed change, and their opposition tends to be categorical. The Wall Street Journal called the proposal to abandon the quarterly reporting cycle “wrong in every possible way.” They dismiss the short-termism argument out of hand – “utter tosh”(again, The Wall Street Journal). The general success of American business, and strong equity market valuations, are reason enough to reject it. “The short‑term logic implies that US business should be performing poorly today. But that is unequivocally not the case…As a fraction of gross domestic product, corporate profits are near all‑time highs.” “The current high levels of US P/E ratios are not obviously consistent with the predictions of the short‑term proponents. Anyone who wished to make the short‑term argument, therefore, needs to also explain the high US P/E ratios.” Robust capital spending is also seen as proof that short-termism is a myth. “Big Tech companies are set to invest almost $400 billion this year in long-term artificial-intelligence projects, and Big Oil explores and builds multibillion-dollar wells and refineries while being publicly listed. And corporate investment overall in the U.S., at 10% of GDP last year, is higher than any time before quarterly reporting was introduced in 1970. Quarterly reporting has been no barrier.” – The Wall Street Journal Advocates of the status quo are worried about the negative consequences of less frequent reporting. Their arguments are based on classical Finance Theory. For example, the stock market (in theory) aggregates vast quantities of information about each company – its assets, its performance, its prospects, its customers, its competitive position in its sector, its role in the global economy – to calculate the correct current price and value of the company’s shares. Prices serve as signals to direct the proper allocation of capital. More frequent updates must always be preferable… because… well, more information must be better than less information, right? “Less frequent reporting would lead to less information and riskier markets,” as well as “greater volatility in securities prices.” It would impair price discovery, and render markets less “efficient.” Distorted asset prices would cause capital misallocation and trigger a cascade of evils – Misallocation elevates risk…which depresses the [the value of investment] in intangible capital and reduces R&D incentives. The resulting decline in expected long-run growth and rise in macroeconomic volatility further amplifies risk. Other consequences of eliminating quarterly reporting could include: A weakening of “market discipline” over company decisions More time and chance for insiders to trade on undisclosed information A higher cost of capital (due to a greater “risk premium”) An unlevel playing field for small investors who lack the resources available to institutional investors to fill in the gaps created by less frequent reporting In sum, opponents of change see the quarterly reporting cycle as a critical guard rail that, if removed, would alter the way markets work and the way public companies are managed, to the general detriment. The Evidence Many of these arguments are conjectural. For example, I know of no way to measure “market discipline” or to empirically estimate “misallocation of capital” on a quarterly or half-yearly basis. Moreover, because all U.S. public companies have been required to report quarterly since 1970, there is no recent comparative data. Some studies have tried to reach back to find a point of reference before the rule change, in, say, the Eisenhower era. However, the economy is much changed since then, as are the accounting and tax rules, the technology base, the financial markets, and management practices. 70-year-old data is just too stale. Percentage of Companies Reporting Quarterly, by Country Chart by author In other countries, however, where quarterly reporting is no longer required, some companies still do report voluntarily on a quarterly basis. EU firms are currently divided more or less equally between quarterly and half-yearly reporters, which sets up a plausible A/B comparison. (We will look at some of this data below, but there is an important caveat. Decisions about reporting frequency are not random. Many confounding factors are involved, including company size, the behavior of peers in the same sector, seasonality of the business, and management style.) The UK provides another natural experiment. Prior to 2014, quarterly reporting was mandatory. Today, “almost all” UK companies report semiannually. This sets up an interesting Pre-Post test (although there are possibly important differences between the two time periods). All that said, and with the appropriate caveats – the non-U.S evidence supports a surprising conclusion: There are no significant differences in outcomes for EU and UK companies, or for capital markets, as a function of reporting frequency. Points of Comparison Analysts have compared quarterly and semiannual reporters in the EU and UK on the basis of: Fundamental measures of business health and corporate performance Levels of investment in long-term projects Quality of Financial Information Available to Investors Company Valuations Evidence of Market Mispricing The Cost of Capital 1. Corporate Performance The only recent study of the effect of reporting frequency on fundamental business performance comes from Goldman Sachs. Analysts compared the business performance of quarterly reporters and semiannual reporters in the EU Stoxx 600 index, and found little difference in return on equity, average net profit margins, and earnings per share growth. EU companies, quarterly and semiannual reporters: Profit Margin, EPS growth, ROE Chart by author 2. Long-Term Investments On the central question of short-termism, one approach is to look at levels of capital expenditure. Long-term investments should draw down earnings and net cash flows in the short term. A short-term bias would show up as a lower level of such investment at quarterly reporters compared with firms which do not report as frequently. The UK offers a double test – first imposing a mandatory quarterly reporting requirement in 2007 and then removing it in 2014. A study for the CFA Institute found that when quarterly reporting was imposed in 2007 it “had no material impact on the investment decisions of UK public companies.” When the mandate was lifted seven years later – “Again, there was no statistically significant difference between the levels of corporate investment of the UK companies that stopped quarterly reporting and those that continued quarterly reporting.” 3. Information Quality A 2023 “Pre-Post” comparison in the UK examined the effect of reporting frequency on the quality of accounting information included in financial reports. The result was “counterintuitive.” “Semiannual reporting is associated with higher accruals quality, reduced accruals manipulation, improved earnings persistence, and increased earnings smoothness compared to quarterly reporting. The results challenge existing beliefs by demonstrating an incremental improvement in financial reporting quality associated with less frequent reporting.” [Emphasis added] An earlier study (2010) looked at the quality of information from the investors’ perspective. The result was also contrary to theory-based expectations. “A firm’s reporting frequency has no effect on the average precision of investors’ information. … In particular, the results of this analysis suggest that investors of semiannual reporters hold more precise pre-announcement information than investors of quarterly reporters.” [Emphasis added] 4. Market Valuation The previously cited Goldman Sachs study found essentially no difference in the price-earnings ratios for quarterly vs semiannual reporting companies in the EU sample. PE Ratios for Quarterly vs Semiannual Reporting Companies in the EU Chart by author 5. Mispricing & Market Efficiency A 2010 study assessed “share price informativeness” for quarterly and half-yearly reporters in several EU markets – a measure of pricing accuracy and market efficiency based on the speed with which share prices anticipate, capture and reflect new earnings information – the efficiency of the price discovery process. It was unaffected by reporting frequency. The same study looked at the surprise caused by the earnings announcement – conceptualized as the difference between investors’ earnings estimates and the actual results. It is measured by the level of abnormal volatility and trading volume on the announcement date. It turns out that earning surprises are not dampened by more frequent reporting. “The announcement-date price variance and share turnover, which capture the information surprise in the announcement, are similar for quarterly and semiannual reporters, despite the fact that quarterly reporters redistribute their information among a larger number of announcements… “The information surprise in quarterly reporters’ announcements is, on average, comparable to or slightly greater than the information surprise in semiannual reporters’ announcements, despite the fact that semiannual reporters potentially have more news to bring.” Surprise reflects a disconnect between investors’ expectations and reality as revealed in the earnings announcement. It can be seen as an indication of the degree of mispricing in the market ahead of the earnings date. By this measure, quarterly reporting is associated with greater mispricing prior to the earnings release than semiannual reporting. 6. Cost of Capital “More information always equates to less uncertainty, and […] people pay more for certainty…Better disclosure results in a lower cost of capital.” This is a powerful and important deduction from classical Finance Theory. It is likely true, to some degree, and is often repeated as an article of faith. It justifies the quarterly cycle (for advocates of the status quo). “The point of requiring timely, standardized financial reporting is to lower companies’ cost of capital. The more transparent and reliable a company’s reporting is, all other things being equal, the lower its costs will be to borrow money or raise equity from outside investors.” The evidence is sketchy at best. “Cost of capital” is typically modeled rather than measured directly. The models depend on a set of complex assumptions, some of which are highly questionable. (For example, the “weighted average cost of capital” that all MBA students learn to calculate assumes that “perfect capital markets exist.”) The issue can also seem to cut both ways. More frequent updates presumably reduce risk and lower the cost of capital for quarterly reporters. But if less frequent reporting is associated with higher quality financial information (as studies cited above show), that should also reduce uncertainty, reduce risk, and thereby reduce the cost of capital for semiannual reporters. One oft-cited study concludes simply that “the benefits of mandatory disclosures are likely to differ across firms.” It should also be remarked that if a company is topically concerned about its cost of capital – say, in connection with a forthcoming funding round – it can always release information on a more frequent basis voluntarily. (And of course, material events must always be disclosed by means of an 8-K filing.) Short-Termism Is Real Then there is the question of mindset, or bias. A survey of 400 Chief Financial Officers of U.S. public companies published in 2005 found that “a surprising 78% of the sample admits to sacrificing long-term value” in order to “smooth earnings.” Nearly 40% said they would give discounts to customers to accelerate future spending plans to increase the company’s reportable sales in the current quarter – forfeiting a percentage of revenue to buff up the 10-Q. The turmoil that can result in equity and debt markets from a negative earnings surprise can be costly (at least in the short-run). Therefore, many executives feel that they are choosing the lesser evil by sacrificing long-term value to avoid short-term turmoil… CFOs argue that the system encourages decisions that at times sacrifice long-term value to meet earnings targets. [Emphasis added] CFO's Responses to an Earnings Miss Chart by author The payoff is said to be predictability. “Predictability of earnings is an over-arching concern among CFOs. The executives believe that less predictable earnings command a risk premium in the market…Managers are willing to make small or moderate sacrifices in economic value to meet the earnings expectations of analysts and investors… and describe a trade-off between the short-term need to ‘deliver earnings’ and the long-term objective of making value-maximizing investment decisions…” At the very least, such measures muddy the quality of the information provided to investors, and may shade towards illegal manipulation. Earnings management and/or manipulation has been the subject of dozens of academic studies, with a variety of definitions and methodologies, so that estimates of the prevalence of these practices vary widely. But it seems clear that the pressure of quarterly reporting deadlines can warp managerial decisions in many cases. So, with regard to “short-termism” the evidence seems mixed. The UK accounting data say no, but survey results confirm a short-term bias among U.S. executives, which is significantly exacerbated by the earnings calendar. That said – after five decades, U.S. public company executives are by now fully habituated to the quarterly reporting cycle – and as opponents of change readily point out, American economic exceptionalism seems unimpaired. Compared to other countries, U.S. businesses are more profitable, the market values of U.S. public companies are higher, and U.S. strategic leadership in many sectors of the global economy (e.g., Tech, Finance, Pharma and Energy) is clear cut. It could be argued that somehow short-termism has served the U.S. economy very well. Perhaps it is an antidote for the complacency which otherwise tends to infect the management mindset in all large and successful organizations. Summary: The Significance of “No Significant Difference’” So, short-term biases may exist, but do they matter? Does quarterly reporting help or harm the company and its investors? Would less frequent reporting impair market functioning? The hard evidence, such as it is, suggests that reporting frequency has very little effect, perhaps favoring semiannual reporting slightly. Summary of Empirical Comparisons Chart by author Ambiguity encourages both sides. The New York Times – which leans towards maintaining the status quo – summarized “numerous studies [that] found no discernible improvements in corporate planning or performance in countries where [less frequent reporting] has been tried” – implying no need for change. But a semantically equivalent rephrasing – “Numerous studies found no discernible difference in corporate planning or performance related to reporting frequency” – could equally well support the argument for joining the global consensus. The ‘Real Problem’ With Quarterly Reporting And there may be very good reasons to do so. Quarterly capitalism has created what has come to be called the “Earnings Game”– where company managers, analysts, and investors maneuver for advantage in the turmoil before and after the official earnings release. It generates a characteristic distortion of the market, and a symbiotic distortion of management behavior. The quality of financial information is often compromised. Mispricings develop. Trading is abnormal and even chaotic. The participants are tempted to pursue quasi-adversarial and sometimes dysfunctional strategies, which open the door to market manipulation, inspire or reinforce short-termist biases in business decision-making, and increase the overall risk for investors. It is likely that retail investors in particular are disadvantaged, trading against professionals who have developed sophisticated techniques for exploiting the market anomalies created by the earnings game. Part 2 of this column will examine this game and its consequences, which make a stronger case for changing the current reporting cycle than the shallow theoretical arguments that have dominated the debate so far. Editorial StandardsReprints & Permissions