Copyright The New York Times

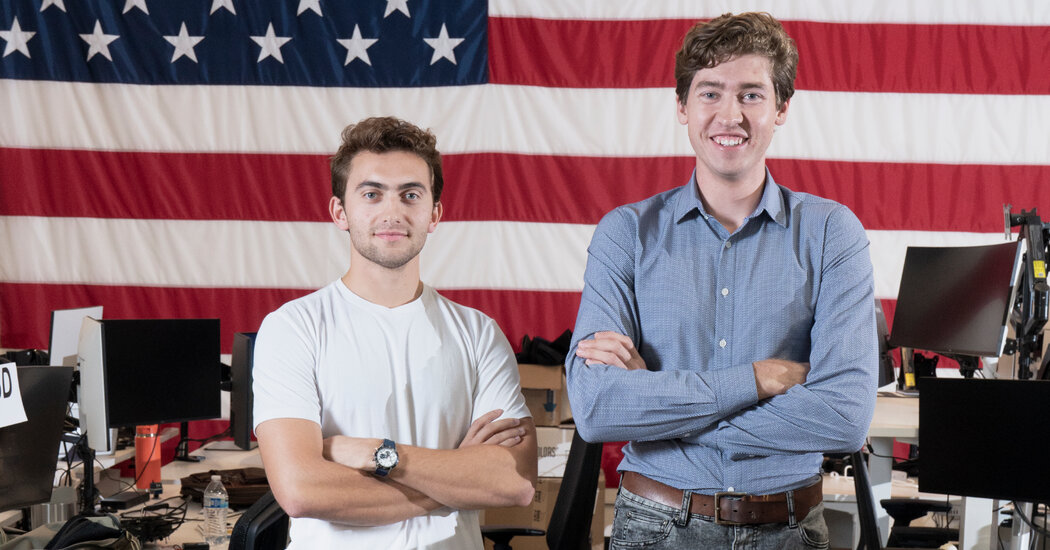

Soren Monroe-Anderson, a champion drone racer, was only 20 years old when he first tried to sell his drones to the U.S. military. He was building them for Ukrainian forces in his parents’ garage with a friend. The military was not interested. “‘You can’t just waltz into the Pentagon as 21-year-olds and sell weapon systems to the D.O.D.,’” said the friend, Olaf Hichwa, recalling the response from a senior Department of Defense official. But two years later, Mr. Monroe-Anderson, now 22, and Mr. Hichwa, who just turned 24, are selling drones to the U.S. Army. Neros, the company they founded in 2023, has been selected to supply its signature drones, called Archer, to the Army, according to documents reviewed by The New York Times. Neros is one of three American drone manufacturers picked as vendors for the first phase of an Army program that is buying low-cost, expendable drones. Although specific financial terms have not been disclosed, the Trump administration has budgeted more than $36 million for the “Purpose-Built Attritable Systems” program in 2026. Neros’s selection comes as military leaders are scrambling to catch up with adversaries who have the ability to mass produce small drones, which have become crucial to modern warfare. The Army aims to buy at least one million drones in the next two to three years, Army Secretary Daniel Driscoll told Reuters on Friday. Although the government shutdown has complicated the military’s efforts to buy drones, some contracts already in the pipeline are moving forward. The Army contract has been closely watched as a bellwether of which American drone companies will dominate the market. For Neros, it comes on the heels of raising $75 million in venture funding, led by Sequoia Capital, and receiving a $17 million Marine Corps contract for thousands of drones, as well as an international drone coalition contract to supply 6,000 drones to Ukraine. Neros’s latest round of funding closed last week, bringing the total raised by the start-up to $121 million and cementing Mr. Monroe-Anderson’s and Mr. Hichwa’s status as wunderkind of the emerging U.S. drone industry. The Defense Innovation Unit, an experimental part of the Pentagon with headquarters in Silicon Valley, has been championing Neros for more than a year, with some drone specialists at the unit affectionately referring to Mr. Monroe-Anderson and Mr. Hichwa as “the boys.” At a flyoff in Alaska this summer, military officials crowded around Mr. Monroe-Anderson as he piloted his drone unmolested toward a device that tried unsuccessfully to jam it. A Neros Archer was one of several drones buzzing around Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth in July when he made a video announcement of policy changes aimed at turbocharging domestic production. In an interview in May, Major Steven Atkinson of the Marine Corps Warfighting Lab recounted searching for American companies willing to supply small drones like the ones being used in Ukraine for less than $2,000 per unit. He came up empty — until he found Neros. “They were pretty young, but they did FPVs,” recalled Mr. Atkinson, referring to first-person view drones, which are flown by pilots wearing special goggles to see video feeds from the drone’s camera, while using a joystick controller to navigate around obstacles. “What they have been able to accomplish is unheard-of,” he said. Mr. Monroe-Anderson and Mr. Hichwa gained their expertise from the world of competitive drone racing. Mr. Monroe-Anderson, who attended high school in New Hampshire, and Mr. Hichwa, who grew up in Maryland, spent their teen years building drones from kits and components they ordered from China. They were so focused on flying and racing that they skipped much of school and their senior proms. Neither has a college degree. The two met in 2017 at a drone racing competition in Muncie, Ind., and quickly began trading ideas about how to make their drones fly faster. Mr. Monroe-Anderson was the better racer, winning the MultiGP World Championship in 2020. Mr. Hichwa was known for his engineering prowess. “He’s a mad genius,” said David Spencer, a fellow racer. In an attempt to best Mr. Monroe-Anderson’s drone, Mr. Hichwa designed a circuit board for his own drone that was lighter than the ones on the market, soldering it himself. He eventually bought an industrial machine from China that mass produced them, selling them to other drone racers for $30 apiece during his junior year. An upgraded version is used in Neros’s Archer. Despite their racing pedigree, challenges remain. Drone racers tend to build systems that are fast and nimble, and require a certain level of mastery. Neros typically trains soldiers on Archer drones for five days. By contrast, DJI, the Chinese company that produces more than 75 percent of the world’s commercial drones, is known for drones that can be flown without any special training. It has been especially challenging to make cheap drones without Chinese parts. Virtually everything they used as teenagers — propellers, motors, batteries, radios, cameras — came from Shenzhen, China. But to sell to the U.S. military, Neros had to build a U.S. supply chain and prove that its drones do not contain critical components from China. Vendors in the United States “would laugh at us,” Mr. Hichwa said. American-made radios could cost as much as $10,000 when he was shopping around for one that cost $30. The founders quickly realized that they would have to build parts themselves and seek suppliers outside the defense industry. Instead of using computer chips common in military equipment that cost hundreds of dollars apiece, Neros used one designed for parking meters, which cost $1 dollar each, Mr. Hichwa said. Their inspiration to build a drone company grew out of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which turned their high school hobby into a world-changing technology. Ukrainians were beating back Russian forces with simple quadcopters jury-rigged with explosives. In the summer of 2023, Mr. Hichwa was working at Skywalk, an artificial intelligence start-up in Palo Alto, when Mr. Monroe-Anderson showed up at his job, begging him to make drones again. Mr. Monroe-Anderson, who opted to forgo college for the time being, had become fixated with helping Ukraine. Mr. Hichwa took it on as a side project, and quickly got sucked in. They conferred on the phone with Ukrainians that Mr. Monroe-Anderson had met on social media and made dozens of drones that snapped together in stacks that were easy to transport. That fall, they went to Kyiv and distributed their drones to Ukrainian soldiers, collecting feedback about how they flew. They met Deputy Prime Minister Mykhailo Fedorov, who is also the country’s Minister of Digital Transformation, who told them that anyone who wanted to supply drones to Ukraine had to be able to produce at least 5,000 per month. “When we meet founders like that, we bet on their trajectory,” said Ian Rountree of Cantos, a venture capital firm that led their angel round. He was impressed that Mr. Monroe-Anderson had managed to attract employees who were far more senior, including Sean Wood, the company’s chief operating officer who had worked at SpaceX for 12 years. Neros employs 80 people, virtually all of whom are older than its founders. But mass production remains a challenge. Last year, Mr. Hichwa traveled to Shenzen to meet the Chinese suppliers who had sent him drone parts when he was a teenage racer. They showed him around their factories as a valued customer, never suspecting that he planned to open a plant of his own. One factory that made the brand of hobbyist drones he flew in high school was now churning out 1,000 drones per day for the Russian military, he said. “They are, to a certain degree, my friends,” Mr. Hichwa said. “But we found ourselves on opposite sides of an armed conflict.” He said he tried to remember as much as he could about the machinery they used, awed by what it would take for Neros to catch up. “We’re barely scraping 2,000 a month,” he said. “And they’re doing that in two days.”