Copyright Reuters

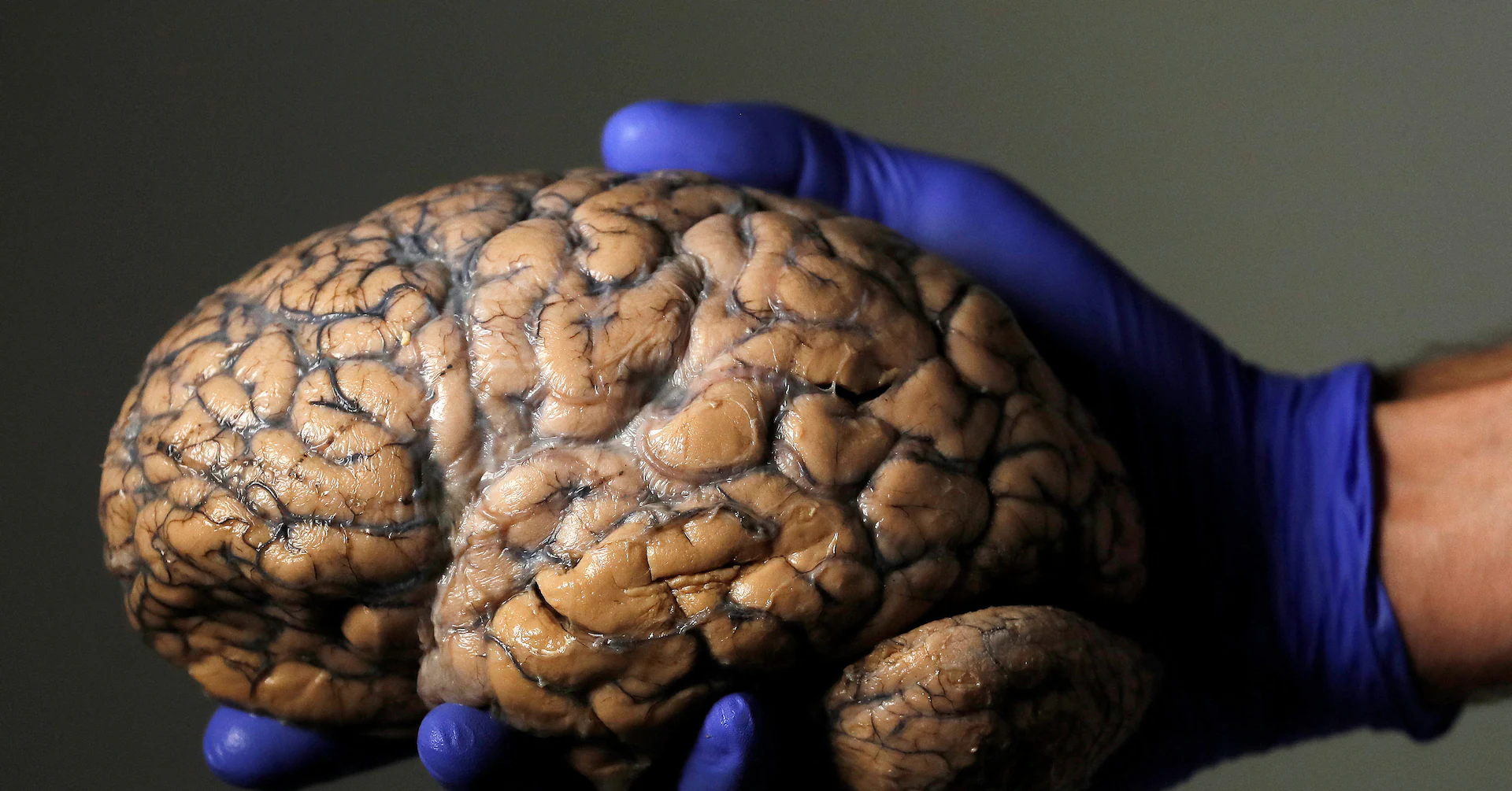

WASHINGTON, Nov 6 (Reuters) - Scientists have reached a milestone in an ambitious initiative to chart how the many types of brain cells emerge and mature from the earliest embryonic and fetal stages until adulthood, knowledge that could point to new ways of tackling certain brain-related conditions like autism and schizophrenia. The researchers said they have completed a first draft of atlases of the developing human brain and the developing mammalian brain. Sign up here. The research focused on human and mouse brain cells, with some work in monkey brain cells too. In their initial draft, the scientists mapped the development of different types of brain cells - tracking how they are born, differentiate and mature into various types with unique functions. They also tracked how genes are turned on or off in these cells over time. The scientists identified key genes controlling brain processes and uncovered some commonalities of brain cell development between human and animal brains, as well as some unique aspects of the human brain, including identifying previously unknown cell types. The research is part of the U.S. National Institutes of Health's BRAIN Initiative Cell Atlas Network, or BICAN, an international scientific collaboration to create a comprehensive atlas of the human brain. "Our brain has thousands of types of cells with extraordinary diversity in their cellular properties and functions, and these diverse cell types work together to generate a variety of behaviors, emotions and cognition," said neuroscientist Hongkui Zeng, director of brain science at the Allen Institute in Seattle and leader of two of the studies. Researchers have found more than 5,000 cell types in the mouse brain. It is thought there are at least that many in the human brain. The research promises important practical applications. "First, by studying and comparing brain development in human and animals, we will better understand human specialization and where our unique intelligence comes from. Second, by understanding normal brain development in humans and animals, we will be better able to study what changes are happening in diseased brains - when and where - both in human diseased tissues and in animal disease models," Zeng said. By gaining this knowledge, scientists hope to achieve more precise gene- and cell-based therapies for a range of human diseases, Zeng said. The hope is that the findings will provide a deeper understanding of autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, schizophrenia and other conditions known to unfold during brain development. The brain regions for which the researchers created atlases for cell type development included the neocortex, which is the part of the brain's outermost layer where higher cognitive function originates, and the hypothalamus, a small structure deep in the brain that helps govern body temperature, blood pressure, mood, sleep, sex drive, hunger and thirst. One study showed that a subset of cells in human brain tumors are similar to embryonic progenitor cells - a kind of cell in the embryo that can change into specific types within a particular brain region - raising the possibility that such tumors may hijack developmental processes to drive malignancy. The researchers identified some unique aspects of the human brain. One example was the prolonged process of differentiation in cortical cell types due to the long period of human brain development from fetus to adolescence compared to the speedier development timeline in the animals. Among the newly identified brain cell types were some in the neocortex and the striatum region, which controls movement and certain other functions. More work is ahead. "The goal is to ultimately understand not only what the pieces of the developing brain are, but also to describe what happens in neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders that develop vulnerability during development," Bhaduri said. "This is also relevant to brain cancer, which my lab also studies, as during brain cancer these developmental pieces re-emerge. So it is really a big goal, and it will take time to fully understand and treat all these disorders. But this set of papers is a nice piece of progress," Bhaduri said. Reporting by Will Dunham, Editing by Rosalba O'Brien