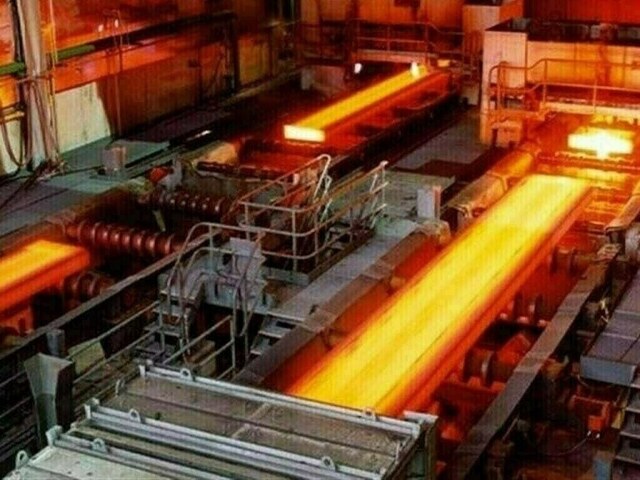

Copyright brecorder

Business Recorder recently reported that the Russian side has proposed two options to Pakistan for the revival and modernization of Pakistan Steel Mills (PSM). The first involves reviving the existing steelmaking facilities based on the Blast Furnace–Basic Oxygen Furnace (BF–BOF) technology, which is the current system used at the PSM. The second option is to establish a new mill using the more modern Electric Arc Furnace (EAF) model. Both technologies have their respective merits and limitations, and a detailed feasibility study covering technical, commercial, environmental, and financial aspects is essential to determine the most viable and cost-effective approach. The BF-BOF process depends on iron ore, coke, and limestone as primary raw materials. PSM, designed originally to operate with imported iron ore and coking coal, required around 1.8 million tons of iron ore annually to sustain its installed production capacity of 1.1 million tons per year. In later years, limited blending of indigenous iron ore with imported high-grade feedstock was attempted successfully. In contrast, the EAF technology is based mainly on iron and steel scrap—about 70 to 80 percent—while iron ore can only be used after conversion into sponge iron through the Direct Reduced Iron (DRI) process. Globally, according to the World Steel Association, about 71 percent of crude steel is produced through the BF–BOF route, while 29 percent is made using the EAF process. Pakistan possesses identified iron ore reserves estimated at 1.5 to 2 billion tons of varying grades, with iron content ranging from 30 to 50 percent. However, only a small fraction is currently proven and commercially exploitable. Indigenous production has remained limited, primarily serving smaller metallurgical industries, while the national steel sector continues to rely heavily on imported iron and steel scrap due to inconsistent supply and quality issues. Between 2005 and 2012, Pakistan even exported modest quantities of iron ore to China, but shipments declined later because of low-grade ore and high transportation costs. The country’s steel industry is largely scrap-based. Pakistan imports an average of 4 to 5 million tons of iron and steel scrap annually—4.7 million tons in 2021—while the PSM has remained idle since June 2015. An additional 0.5 to 1.0 million tons of scrap is generated locally, mostly through the ship-breaking industry. Pakistan’s crude steel production in 2024 stood at 4.1 million tons, accounting for only 0.22 percent of global output, ranking 33rd among the 50 steel-producing nations, according to the World Steel Association. To bridge the demand-supply gap, Pakistan annually imports iron and steel products worth around USD 6 billion, including scrap valued at approximately USD 1.6 billion. With an appropriate beneficiation programme to remove impurities such as phosphorus and silica, PSM could progressively utilize domestic iron ore, reducing dependence on imported raw materials. Punjab holds the largest share of these reserves, amounting to about 2,000 million tons across a 975-square-kilometer area till early 1980s. Major deposits are located at Makerwal-Sho (706 million tons), Chichali near Kalabagh (369 million tons), Dera Ghazi Khan (268 million tons), and Chiniot (610 million tons), though most are of low-grade quality containing 30-34 percent iron. The Chiniot–Rajoa iron ore deposits, discovered in 1989, are of far superior quality, with iron content ranging from 41 to 77 percent in the measured reserves of 110 million tons. These deposits are of strategic and economic importance, potentially meeting up to 40 percent of Pakistan’s steel demand if fully developed. Classified into smelting, high-, medium-, and low-grade categories, they have been confirmed as commercially viable by international consultants, with both Chinese and European experts validating their vast potential. The Chiniot-Rajoa ores are comparable in quality to those in Russia, Brazil, and India, and exploration across the larger 2,000-square-kilometer region may reveal even greater reserves. Similarly, the Kalabagh–Chichali deposits, discovered in the 1950s and estimated at around 500 million tons, contain high-grade ore suitable for use in steelmaking. Yet successive governments have neglected their development, leaving these valuable resources untapped. Further reserves—around 300 million tons—exist in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, with the Dilband (200 million tons) and Nokundi (50 million tons) deposits holding promise as alternatives to imported iron ore. These medium- to high-grade ores (38–50 percent iron) can be upgraded through beneficiation to achieve up to 64 percent iron content. In 2003, PSM began using Dilband–Nokundi ore in blended form, and by 2008, it had reached 100,000 tons annually, about 10 percent of its requirement at the time. Pakistan exports of iron ore in the past were of Dilband-Nokundi origin. The development of these resources, along with the Chiniot–Rajoa deposits, is of strategic importance for import substitution and foreign exchange savings. In conclusion, the revival of Pakistan Steel Mills offers a unique opportunity to align industrial modernization with national resource development. The choice between BF-BOF and EAF technologies should be guided by technical feasibility, long-term cost efficiency, and the potential for utilizing indigenous raw materials. Whichever path is chosen, technological upgrade and environmental sustainability must remain central objectives. With prudent planning, Pakistan can not only restore PSM to its former role as the backbone of industrialization but also move decisively toward self-reliance in steel production—transforming a long-neglected asset into a pillar of economic strength. Copyright Business Recorder, 2025