Copyright news18

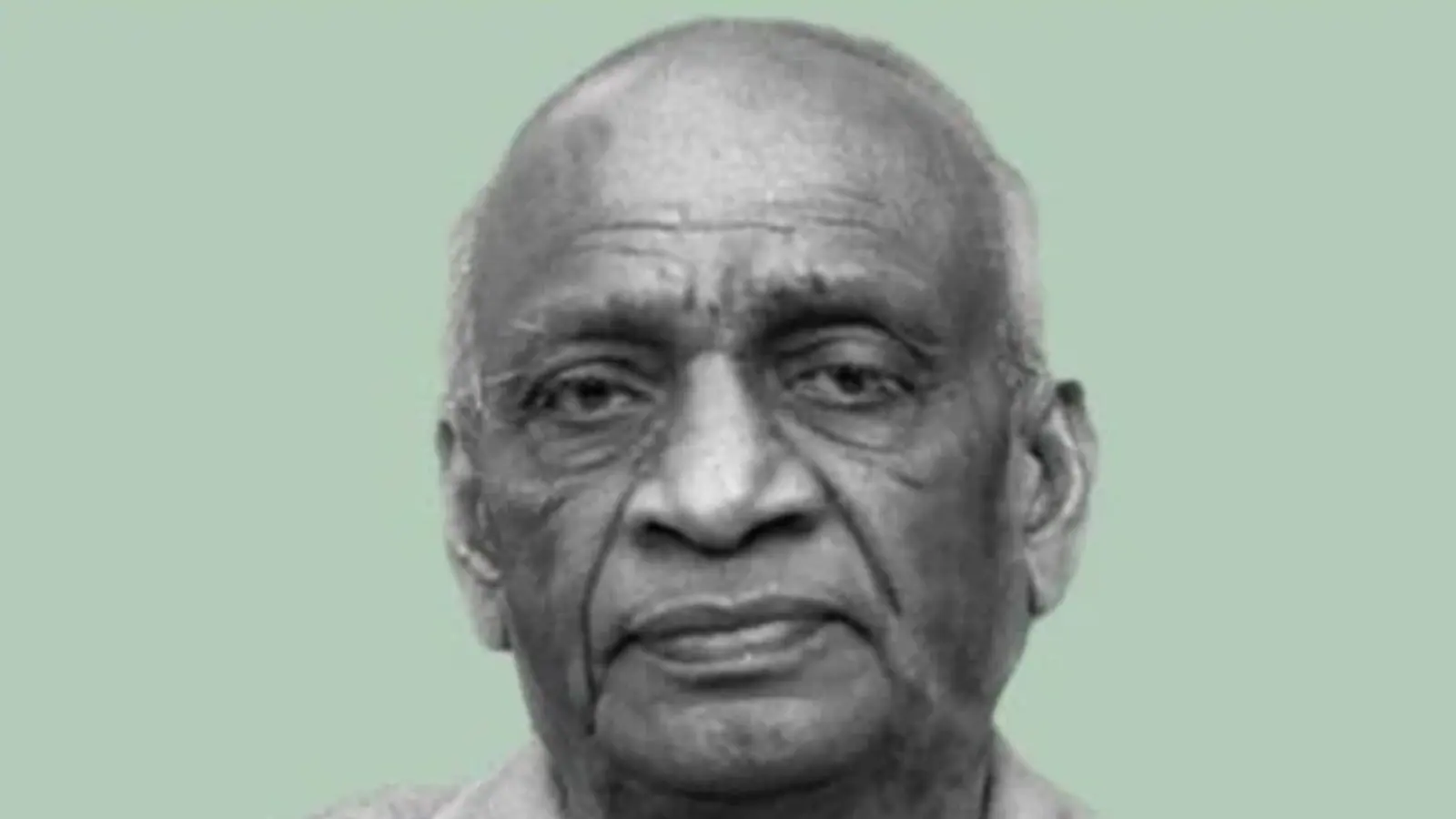

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, whose 150th birth anniversary falls on 31st October, was among the lodestars of the first-generation leaders that navigated India before and after independence. Reminisced as the Iron Man of India, his case, however, has been different from that of Nehru and Gandhi, the two icons considered, and rightly so, secularists with hardly any blemish. Patel carries the burden of historical (mis)judgment and is often labelled as anti-Muslim. Does this charge stand the honest audit of the past? Let’s first understand what made Patel a villainous figure in some quarters. While Sardar started as a true lieutenant of Gandhi Ji and a champion of Hindu-Muslim unity from 1917 onwards, French orientalist author Christophe Jaffrelot writes that he meandered to Hindu fundamentalism in the later phase. Perhaps as a reactionary to the Muslim League’s aggressive separatist politics! The change in Patel’s attitude came about when Jinnah took over the League leadership in 1937; his diatribes against Hindus and the Congress upset him considerably. The two-nation theory shook his faith, says late Muslim scholar Rafiq Zakaria in his book, Sardar Patel and Indian Muslims. At the same time, Patel also began to show some sympathy to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and said publicly in Jaipur in 1948 that he willed “to turn the enthusiasm and discipline of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh into right channels”. At this time, many in the Congress, including Nehru and Maulana Azad, felt that he was drifting towards the Hindu right. Azad, though, later subdued his views and praised Patel’s administrative skills in his autobiography. The picture of Patel as a “communalist” was etched more in the Muslim psyche when, as a Home Minister and Deputy Prime Minister, he ordered Operation Polo to crush pending rebellion in the state of Hyderabad after Nizam refused accession into India and instead mulled to secede to Pakistan or run as an independent state in the heart of India. But beneath the veneer of perceived facts and believed notions has been lying the truth. Sardar, as noted by Jaffrelot himself, made a firm solidarity among all Indians a kernel of his faith quite early in his career as a political and social worker. When the Khilafat Movement was at its peak and it was solely a Muslim cause, Patel was among those who followed Gandhi in supporting Muslims. Jaffrelot quotes Sardar’s sentiments at that moment: “As a matter of fact, it has been a heartbreaking episode (the annihilation of Turkish Caliphate) for the Indian Muslims, and how can Hindus stand by unaffected when they see their fellow countrymen thus in distress?” Muslims, Patel averred, originally belonged to India and thus their cause would be shared by Indians. Patel was a leading barrister in criminal law at the Ahmedabad bar when he joined Gandhi ji and changed his style and appearance completely. He quit the Gujarat Club, dressed in the white cloth of the Indian peasant, and started following a more traditional Indian lifestyle. He led mass campaigns of peasants, farmers, and landowners of Kheda, Gujarat, against the decision of the Bombay government to collect the full annual revenue taxes despite crop failures caused by heavy rains. It benefited all, including Muslims. In his leadership, he was ruthless only against the authorities and genial towards his fellow countrymen. It earned him the sobriquet Sardar, which, even though commonly known then, is actually a word that resonates most among Muslims. During the freedom struggle, Patel emphasised that “Hindu-Muslim unity is like a tender plant. We have to nurture it extremely carefully over a long period, for our hearts are not as yet clean as they should be”. He actually echoed Gandhi when it came to communal harmony. Like Gandhi, he could chastise both Hindus and Muslims for carrying divisive ideas. His brusque tone in the 1948 Calcutta speech was directed against any residue of separatism that Indian Muslims must have nurtured even after the painful partition. His anger targeted Pakistan rather than Muslims: “Let Pakistan become heaven itself, we will enjoy the cool breeze coming from it… but they must know that they are a different country.” This was the only time when he spoke about any possibility of Indian Muslims having sympathy with Pakistan but made it clear that it was a different country and Indian Muslims are out to take part in building future India, as equal Indians. Dr KM Munshi, a key member of the Constitution Drafting Committee, and Rajarishi Purushottamdas Tandon, a former president of the Congress, both closest to Sardar, argued vehemently against the incorporation of the word “propagate” in the Fundamental Rights enshrined in the Constitution of India during debates in the Constituent Assembly. But despite stiff opposition, Patel used all his prestige and influence to ensure that the word “propagate” was incorporated in Article 25 of the Constitution as a part of the Fundamental Rights of all religions in India. He was also the Chairman of the Minorities Committee of the Constituent Assembly, where he championed the cause of Sarva Dharma Maitri, aka Inter-Faith Harmony. Even as head of the advisory committee of the Constituent Assembly, he allowed debate and vote on reservation to Muslims in legislature and government jobs that demanded rigorous recruitment tests like Indian Civil Services. Interestingly, Muslim members like Syed Sadulla opposed such a proposition. Gandhi Ji, Patel’s mentor, would dismiss any charge of communal bias against Patel. For Gandhi, it was Patel’s roughness that emitted a wrong signal, but deep down he was a staunch secularist. “Sardar has a bluntness of speech which sometimes unintentionally hurts, though his heart has expansion enough to accommodate all,” Gandhi once responded to questions posed to him about Patel’s perceived communal tendencies. Gandhi’s scion, Rajmohan Gandhi, who wrote a biography of Patel, writes that Patel should be judged by his actions, not words which often are interpreted out of context. In his actions, writes Rajmohan Gandhi, there was little to fault Patel, who as Home Minister would often personally travel to communal flashpoints to ensure that Muslims are not attacked. Like in September 1947, as reports emerged of threats to those taking shelter in the Dargah of Nizamuddin Auliya in south Delhi, Patel’s private secretary Shankar records Patel’s response. “Sardar wrapped his shawl round his neck and said ‘Let us go to the saint before we incur his displeasure’. We arrived there unobtrusively. Sardar spent a good 45 minutes in the precincts, went round the holy shrine in an attitude of veneration, made enquiries here and there of the inmates, and told the police officer of the area, on pain of dismissal that he would hold him responsible if anything untoward happened,” as quoted by Rajmohan Gandhi. Patel’s visit actually restored calm in the area immediately. Later in the same month, as reports came that Sikhs in Amritsar intended to attack Muslim convoys on their way to Pakistan. Patel, writes Rajmohan Gandhi, travelled to Amritsar and famously made this appeal: “Here in this very same city, the blood of Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims mingled in the bloodbath of Jallianwalla Bagh. I am saddened to think that things have come to such a pass that no Muslim can go about in Amritsar and no Hindu or Sikh can even think about living in Lahore.” In fact, when Pakistan became a reality, there was constant pressure on Vallabhbhai to declare India a Hindu state. He resisted it to his last breath. Noted historian S. Gopal has observed, “Patel is usually depicted as a supporter of Hindu chauvinism but actually his major concern was national unity”. He was as scathing with kings, princes and nawabs of princely states as he was with communally extremist groups. He feared none, spared none so long as the integrity of India was at stake. United India was his sole mission. He was not patronising towards Muslims and neither had he expected them to prove anything other than integrating themselves into India. India’s first President, Dr Rajendra Prasad, noted in his diary on May 13, 1959: “That there is today an India to think and talk about is very largely due to Sardar Patel’s statesmanship and firm administration”. The only lacuna, according to Rafiq Zakaria, was that Patel didn’t write his own accounts unlike Gandhi and Nehru and even scholars paid sombre attention to record his life and statesmanship. It left leeway for both who venerate him and violate him. Today, as the BJP-led central government strives to cherish his legacy, Patel’s image by default turns somewhat murky to Muslims. But, as Rafiq Zakaria commented in his book, if Hindus adore Patel, Muslims have to understand him. Once they will understand, claims Zakaria, they will know that Sardar all his life emphasised on “the unity of hearts” between Hindus and Muslims. The author is the National Chairman of Muslim Students Organisation of India MSO. He writes on a wide range of issues, including Sufism, Public Policy, Geopolitics and Information Warfare. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.