Copyright Rolling Stone

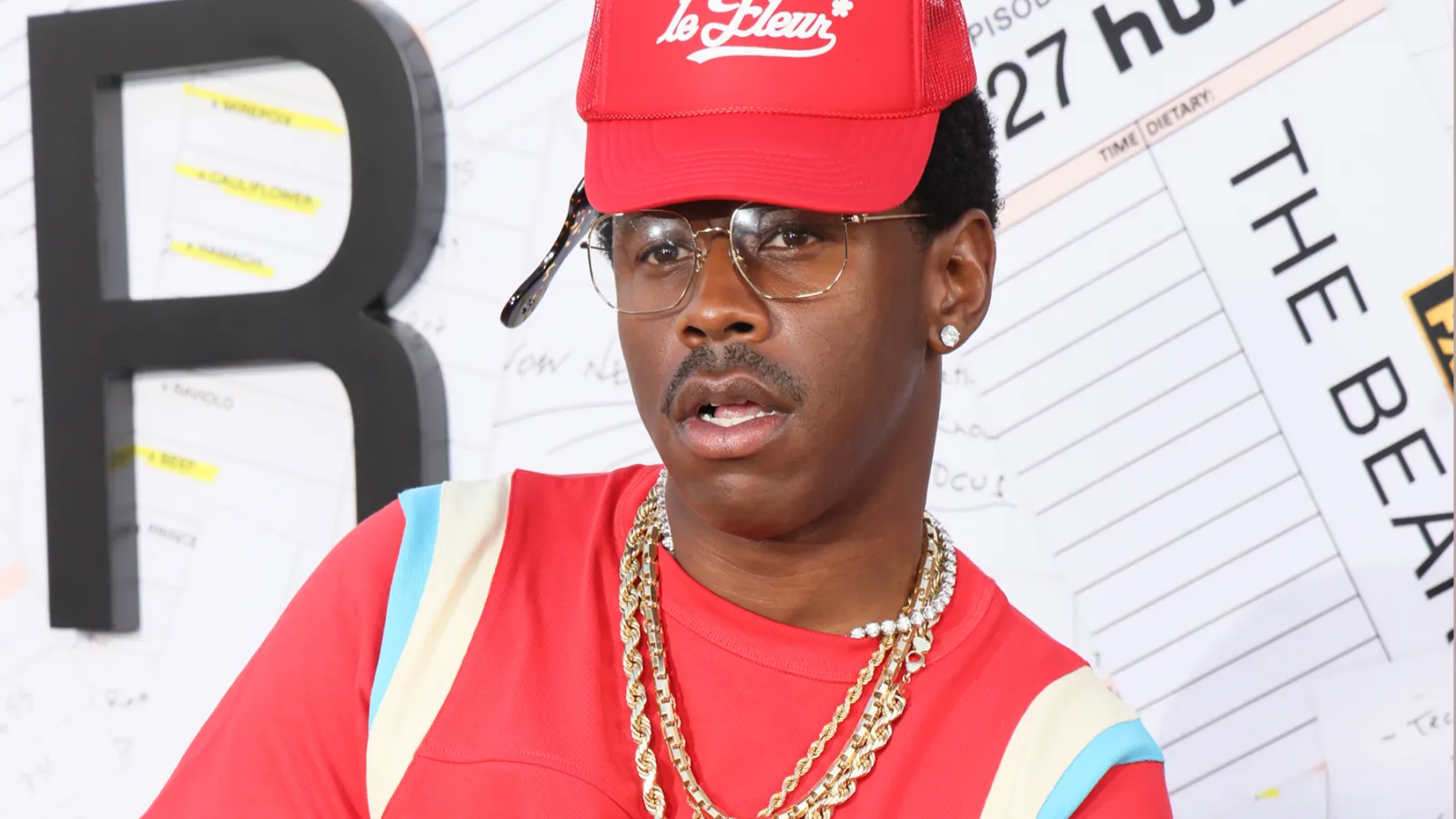

In 2015, alongside the release of his fourth album Cherry Bomb, Tyler, the Creator released a limited-edition zine as part of his Golf Media project featuring interviews with people like Seth Rogen, as well as ephemera related to the album, such as a scan of the Moleskine notebook where he jotted down his ideas. He dedicates a few pages in the book to highlight the albums he’d been most influenced by: Clipse’s Hell Hath No Fury, Pharrell’s In My Mind, and, instructively, D’angelo’s 2000 masterpiece Voodoo. In his write-up about the late R&B luminary’s album, Tyler recalls getting $30 from his grandmother for his ninth birthday and buying the CD. “My favorite videos to see on BET were ‘Get Up’ by Amel Larrieux and ‘Left Right’ by D’Angelo,” he wrote. “I bought both albums and I will never regret that.” Last week, following D’ Angelo’s tragic passing, Tyler took to Instagram to pay tribute to the artist who had such an impact on his music early on—except, things quickly went haywire. After a heartfelt post in which he reiterated much of what he wrote ten years ago, comments came rushing in, either dismissing the post and clamoring for new music or questioning who D’Angelo was in the first place. As he often does, Tyler took to Twitter and criticized the segment of his fanbase he perjoratively called “Sun Seekers,” a.k.a. the white fans who were unaware of D’Angelo’s legacy. A post from the popular hip-hop news aggregator Kurcco pointed out that Tyler himself liked a tweet that stated, “Nigga has charlie wilson, erykah badu, dj drama etc. collaborations and they still refuse to engage with black art on any meaningful level. very cannibalistic.” The argument that emerged suggested that Tyler, the Creator, in his early, highly offensive Odd Future work, cultivated a fanbase of white incels who were inherently hostile to Black music. The refrain was that he should have expected these reactions to his D’Angelo tribute and has no one to blame but himself. The evidence for this was Tweets and screenshots from his early career, where Tyler did everything from criticizing George Floyd protests to pulling “edgy” stunts like dressing in a Klan robe, and selling merch featuring a rendering of the offensive Sambo figure. More than provocations from an artist conveying a particular (misguided) form of racialized postmodern angst, these data points have come to serve as proof that Tyler hates himself and his own Blackness. It’s the type of conversation tailor-made for the internet. Editor’s picks The notion that Tyler cultivated an audience of white incels flies in the face of the many Black fans Odd Future had at the very beginning. This was a crew of Black teenagers making sonically adventurous music that, in fact, garnered a great deal of young Black listeners. That’s to say nothing of the growth in Tyler’s audience over the past 15 years. Even if you take the argument on its face, it doesn’t explain his contemporary fanbase, who, mathematically, outnumber those early fans by now. It’s also just revisionist history. On the same feeds where Tyler shared offensive outbursts in the early 2010s, he’d express his admiration for the likes of Erykah Badu and D’Angelo. The whole point back then was that Tyler contained contradictions. The anger expressed in his music was not unlike Eminem, whose brash internal frustrations with masculinity fueled the most brilliant and simultaneously violent, misogynistic, and homophobic music of his career. You were never supposed to take these things literally. The illogic of this talking point extends to its conclusion: The suggestion that the past decade of work from Tyler, with its open embrace of both classic Black musical forms as well as more traditionalist rap (See: “That Guy,” his buoyant take on Kendrick Lamar’s “Hey Now”), is all a ploy to latch on to new Black fans in order to remain relevant. To believe this, you would simply have to ignore anything that has occurred in real life as it relates to Tyler, the Creator, and Odd Future. You’d have to rely on a curated retelling of history rather than any lived experience, which is precisely where the internet lives. In the gap between content and context. Related Content Tyler’s love for hip-hop as an art form in the purest sense of the word is almost annoyingly well-documented. It was only last year when he got in a dust-up with the internet’s white rapper of the month, Ian, calling out his style and affect as offensive during an interview with Maverick Carter. “There’s this white kid, regular Caucasian man, who’s like mocking Future and Gucci Mane — rap music — and people are like, ‘Yo, this shit hard!’ … and it’s like, bro, it’s parody. He’s not even trying to make rap better,” he said. Tyler booked Roy Ayers for Camp Flog Gnaw in 2017 and just this past March, after Ayers’ death, he shared a heartfelt tribute to the neo-soul pioneer, calling him “the base of my sound.” All of this is to say that, if anything, the average Tyler, the Creator fan is more likely a huge snob about how much they appreciate artists like D’Angelo than a white kid who simply hates Black music. What clearly frustrated Tyler was that the commenters were more focused on getting new music from him than on what he was actually posting. This is easily the most common problem faced by celebrities with their online fans, who are often so cravenly obsessed that they miss the bigger picture. It doesn’t help that Tyler, like basically every other rapper to gain popularity in the past 20 years, has a large white audience — a phenomenon that predates Tyler by at least a generation. However, it’s a leap to call them “incels” and unclear what that designation, a term focused on lonely men and misogyny, would even mean in this context. Even still, today’s so-called white incels — fueled by a steady diet of controversial streamers like Adin Ross and N3ON — are not listening to Tyler, the Creator, someone who has an album called Flower Boy. This is not even the first time in the past year that Tyler’s old material has resurfaced online, spawning a familiar ouroboros of online discourse, shrouded in the language of accountability and well-meaning politics, that mostly serves to feed the beast of online engagement. Last year, in response to Tyler briefly de-throning Taylor Swift on Spotify’s “Top Artists — Global” chart, Swifties started sharing screenshots of Tyler’s old lyrics, spurring a days-long conversation around his past misogyny. He rebuffed the controversy in typical fashion, declaring during a show in Boston that, “I got Swifties all mad at me with their racist a-ss … Bitch, go listen to ‘Tron Cat’. I don’t give a fk, h. They gon’ bring out the old me.” With this latest flare-up, the venom is certainly more potent. Tyler’s relationship to his Blackness — from early claims that he encouraged white fans to say the N word (the actual quote is boneheaded but far less sinister), to disparaging comments he’s made about Black women — is in many ways much more fertile ground for criticism. As such, TikTok creators have started weighing in with anecdotes about Tyler’s alleged anti-Blackness that, of course, dovetail into stories about their own lives. Trending Stories In fairness, many online commentators acknowledge some level of growth on Tyler’s part but suggest that, since he has not publicly and explicitly apologized for his past behavior, he’s paid insufficient penance for his actions. This latest outburst has been roundly described as Tyler receiving his “lashings.” It’s in that language where we can see what’s really happening. There is very obviously no excuse for the kinds of posts and commentary Tyler was known for early in his career, but the internet is fueled by bloodlust, not justice. So much so that a tribute to D’Angelo has turned into a nearly weeklong discussion about tweets from more than a decade ago. All the while, Chris Brown is on a Stadium world tour. The brand of discourse increasingly prevalent in online spaces, where we whittle individuals down to digestible data points, is useless in having actually productive conversations about anti-Blackness, or art, or misogyny. It’s all content meant to poke and prod at the complex issues central to our identity, driving up intense emotions that inspire endless posts. The more one dimensionally you can paint someone, the better. Whereas Tyler, the Creator may have ridden in on a wave of optimism about the Internet as a tool for giving a voice to the misunderstood, it’s grown into a force that decimates the nuance and context that make us human.