Copyright thediplomat

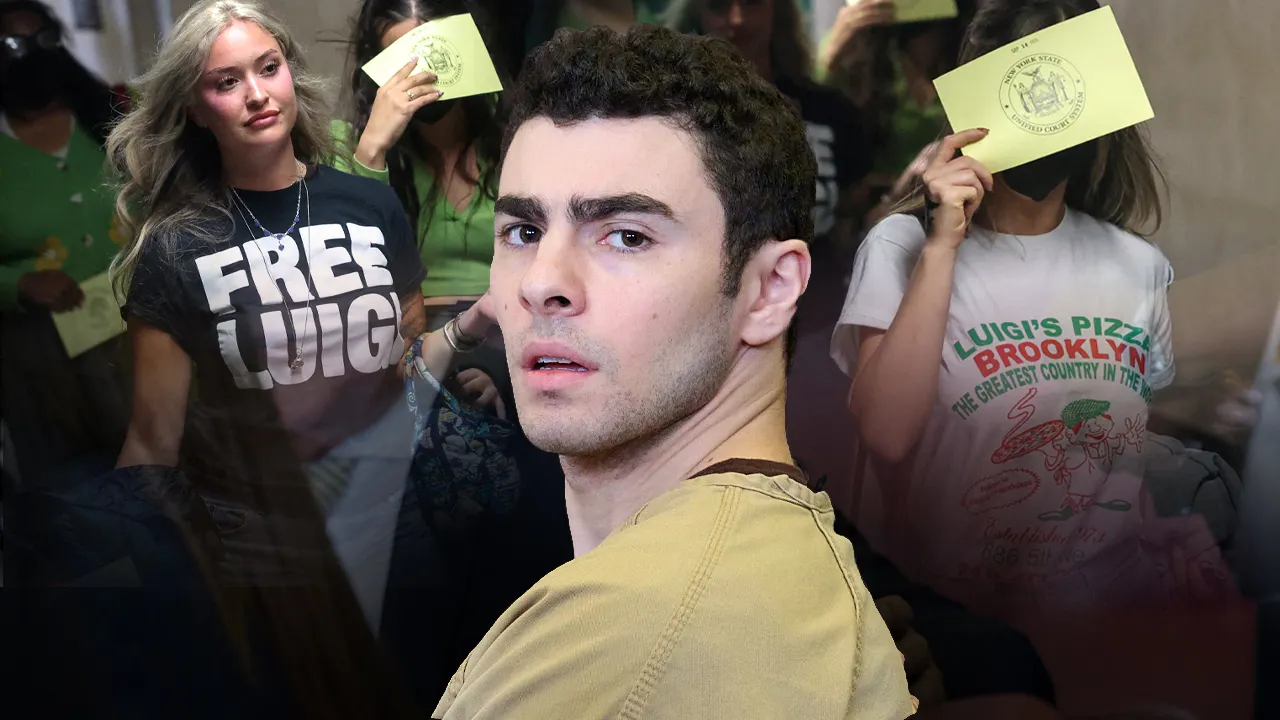

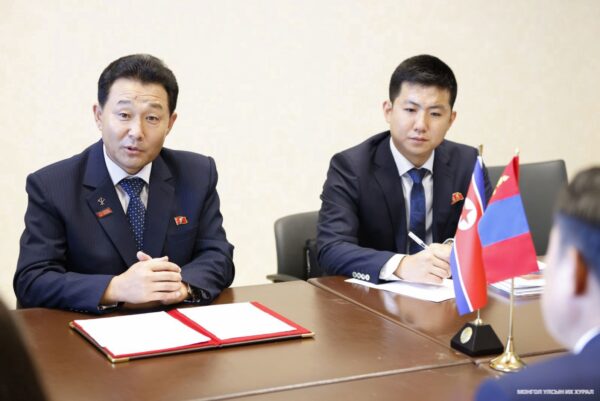

In the intricate geopolitical web of Northeast Asia, Mongolia has long clung to its identity as a “neutral bridge,” leveraging its “Third Neighbor Policy” to carve out autonomy amid the overlapping influence of China and Russia. What began in the 1990s as an expedient to reduce economic dependence on Beijing and Moscow has evolved into a values-based diplomatic stance, earning Ulaanbaatar credibility as a nonaligned mediator. Yet between 2024 and 2025, three converging crises shattered this delicate balance: the collapse of the soft power narrative embodied by the Mongolia-South Korea co-produced film ”On the Way to the South,” the exposure of a South Korean spy scandal, and a diplomatic crisis sparked by the defection of a North Korean interpreter. Together, these incidents laid bare a sharp contradiction at the heart of Mongolia’s neutrality: how to reconcile humanitarian idealism with economic pragmatism, and how to safeguard national sovereignty while appeasing both Seoul and Pyongyang. Coming in 2025 – the 35th anniversary of Mongolia-South Korea diplomatic ties – and on the heels of Ulaanbaatar’s renewed engagement with Pyongyang in 2024, the crisis has become a defining test of Mongolia’s diplomatic maturity. Soft Power Ambitions Collide with Sovereign Compromises Premiering in Ulaanbaatar in September 2024 and Seoul in April 2025, ”On the Way to the South” was intended to consolidate both countries’ soft power. Co-directed by South Korea’s Sangrae Kim and Mongolia’s Battulga Suvid, the film eschewed political grandstanding for a human-centric narrative: a North Korean mother fleeing border patrols with her child, a Mongolian border guard torn between duty and compassion, and a defector grappling with separation trauma. Starring prominent Mongolian actors Sarantuya Sambuu, Erkhembayar Ganbold, Samdanpurev Oyunsambuu, and Zamilan Bold-Erdene alongside South Korean stars Park Kwang-hyun, Oh Su-jung, and Choi Jun-yong, the film deliberately framed Mongolia as a “moral mediator” – rejecting Seoul’s hardline stance toward Pyongyang while disavowing North Korea’s isolationist policies. The film’s release was meticulously timed to coincide with the 2025 bilateral anniversary, aiming to enhance Mongolia’s voice in Korean Peninsula mediation while aligning with South Korea’s “New Northern Policy,” which positions Mongolia as a Eurasian resource hub. Domestically, it stoked national pride in a small nation contributing to regional stability; internationally, it successfully rebranded the Third Neighbor Policy from a mere economic diversification strategy to a diplomatic framework rooted in humanitarian values. This narrative resonated because Mongolia remains one of the few countries to maintain stable long-term relations with both Koreas since the Cold War. Yet this idealistic vision crumbled within months amid an espionage scandal. In late 2024, Mongolian authorities arrested two officers from South Korea’s Defense Intelligence Command (KDIC) – a lieutenant colonel and a major – accusing them of recruiting Mongolian intermediaries to infiltrate North Korea’s embassy in Ulaanbaatar. The act violated the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, constituting a direct infringement of Mongolia’s sovereignty. Ulaanbaatar initially issued a stern condemnation, calling the incident a “serious breach of trust,” but reversed course after KDIC Director Moon Sang-ho personally traveled to Ulaanbaatar to apologize. Mongolia dropped the charges and released the officers. This compromise stemmed from Mongolia’s deep economic reliance on South Korea, yet it exposed diplomatic double standards: Ulaanbaatar was simultaneously deepening friendly engagement with Pyongyang, eroding its neutral image. More alarmingly, an investigation by South Korean Special Prosecutor Cho Eun-seok revealed potential links between the spy operation in Mongolia and former President Yoon Suk-yeol’s declaration of martial law less than two weeks later. The probe found the KDIC’s actions were a deliberate attempt to fabricate a security crisis over North Korean threats, providing a pretext for Yoon to suspend civil liberties and dissolve parliament in an authoritarian power grab. Notes from former KDIC Director Noh Sang-won – now on trial for treason – detailed plans to “launch provocative attacks along the Northern Limit Line (NLL).” Lee Seung-ho, the former operational chief of South Korea’s Joint Chiefs of Staff, confirmed the former defense minister had ordered drones to infiltrate North Korean territory. Internal KDIC memos also referenced using “abandoned balloons” equipped with propaganda or incendiary devices to provoke a North Korean response. Mongolia’s territory had unwittingly become a stage for this political conspiracy, violating both its sovereign principles and cherished neutrality. The Defector Crisis In August 2025, the defection of an interpreter during a high-level North Korean academic delegation’s visit to Mongolia worsened the country’s diplomatic predicament. Led by Tae Hyung-chul, president of the Academy of Social Sciences, the delegation marked Pyongyang’s first senior academic mission to Mongolia in seven years. Tae and his group were tasked with promoting the narrative that “Seoul has abandoned reunification.” Chaos erupted during the visit, however, when an accompanying interpreter sought asylum at South Korea’s embassy in Ulaanbaatar. According to Japan’s Kyodo News, Pyongyang responded with an unprecedented retaliation: recalling its ambassador to Mongolia – the first such move since 1999 – ending Oh Seung Ho’s eight-year tenure. This retaliation stood in stark contrast to the warming of Mongolia-North Korea relations in 2024. That year, Mongolia became the first country besides China and Russia to increase embassy staff in Pyongyang following the COVID-19 pandemic. In January, Mongolian Ambassador Luvsantseren Erdenedavaa presented his credentials to Choe Ryong Hae, chairman of the Presidium of North Korea’s Supreme People’s Assembly, with both sides commemorating the 75th anniversary of diplomatic ties and the 35th anniversary of Kim Il Sung’s visit to Mongolia. In March 2024, North Korean Vice Foreign Minister Park Myong Ho led a delegation to Mongolia – the first from Pyongyang’s Foreign Ministry (Ulaanbaatar has repeatedly invited Choe Son-hui, North Korea's female Foreign Minister, to visit Mongolia. However, in recent years, she has visited Moscow and Beijing more frequently) to Ulaanbaatar since the pandemic. These interactions reflected Pyongyang’s recognition of Mongolia’s decision to keep its embassy open during the pandemic and trust in its neutral stance. On July 31, 2025, Chairman of the State Great Khural, Amarbayasgalan Dashzegve held another official meeting with Chairman of the Supreme People's Assembly of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea Pak In Chol. The Mongolian side emphasized its commitment to further strengthening long-term friendly cooperation based on the profound traditional friendship between the two countries, prioritizing the common interests of their peoples, and supporting regional peace and prosperity. The North Korean side expressed gratitude for the enthusiastic and friendly exchanges on bilateral relations and reaffirmed its commitment to close collaboration to advance stable and long-term cooperation between the two countries. The two sides also exchanged views on enhancing inter-parliamentary cooperation. The interpreter’s defection shattered this trust, with North Korea issuing a stern warning: it would not tolerate Mongolia becoming a “transit hub for defectors” or a “platform for South Korean conspiracies.” Faced with the crisis, Mongolia adopted a “strategic silence,” neither confirming nor denying the defection. Despite international accusations of “hypocrisy,” the choice was a pragmatic one for a small nation: prioritizing avoidance of direct confrontation with Pyongyang and long-term regional stability over short-term moral grandstanding. Still, the cost of silence was significant: it disconnected Mongolia’s actions from the humanitarian narrative of ”On the Way to the South,” seriously undermining its credibility as a “neutral mediator.” More importantly, the incident thrust Mongolia’s long-concealed role as a secret transit country for North Korean defectors into the geopolitical spotlight. Mongolia-North Korea relations have long been guided by pragmatism. The two countries established diplomatic ties in 1948, with Mongolia among the first to recognize Pyongyang. Even after Mongolia’s democratic transition in 1990, bilateral relations endured. In 1999, North Korea closed its embassy in Ulaanbaatar citing “financial difficulties” – a de facto protest against Mongolia’s growing closeness to South Korea. Ulaanbaatar subsequently took initiative to repair relations by facilitating a visit by North Korean Foreign Minister Paek Nam Sun in 2002 to sign a new Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation, and enabling the re-opening of Pyongyang’s embassy in 2004. Between 2004 and 2019, Ulaanbaatar hosted up to 5,000 North Korean workers and provided food aid during times of famine. This low-key engagement maintained crucial communication channels, laying the groundwork for Mongolia’s mediatory ambitions. The 2025 defection crisis squandered decades of accumulated trust, leaving Mongolia’s North Korea policy mired in reactive crisis management. Economic Dependence: The Shackles of South Korean Influence Mongolia’s series of compromises in 2024-2025 stemmed from severe economic vulnerability. Over 80 percent of its trade relies on China and Russia, making its economic lifeline vulnerable to fluctuations in their economies and policy shifts. The Third Neighbor Policy is essentially a survival strategy to mitigate this risk. By 2025, South Korea had emerged as the policy’s core pillar: Seoul’s semiconductor and electric vehicle industries create a strong demand for Mongolia’s silver, molybdenum, coal, copper, and rare earths (critical minerals), forging a deeply complementary economic bond built on earlier energy and infrastructure cooperation. Economic data from 2025 underscored the urgency of this dependence. Amid a slowdown in China’s economy, Mongolia’s exports to China fell by 9.4 percent in the first three quarters, with coal revenues plummeting by 41 percent. While South Korea sought to fill the resulting gap, the actual data indicates that the outcome was less favorable for Mongolia: according to South Korean statistics, bilateral trade volume exceeded US$550 million in the first three quarters of 2025. Notably, although total trade volume rose by 19 percent, this growth was driven by 21.2 percent increase in South Korea’s exports to Mongolia, whereas South Korea’s imports from Mongolia declined by 16.3 percent. Seoul pledged to establish a “Mongolia-South Korea Rare Earth Cooperation Center” in November 2025 to promote joint exploration and smart mining. The ongoing negotiation of an Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) promises not only immediate economic relief but also critical technology for Mongolia’s sustainable development. This economic allure has gradually translated into significant South Korean diplomatic influence. Amid these diplomatic and economic crosscurrents, high-level parliamentary diplomacy emerged as a critical tool for Mongolia to navigate the Korea divide. In April 2025, even as South Korea descended into domestic turmoil – with former President Yoon facing impeachment over his 2024 emergency decree – National Assembly Speaker Woo Won-sik led a delegation to Mongolia. His framing of Mongolia as a “core partner for regional stability” implied a quid pro quo: economic support contingent on Ulaanbaatar aligning with Seoul on the Korean Peninsula. After three months, on July 30, 2025, Chairman of the State Great Khural of Mongolia Amarbayasgalan Dashzegve held an official meeting with Speaker of the Republic of Korea National Assembly Woo Won-sik. Notably, this meeting came just one day before Amarbayasgalan would hold a similar meeting with North Korea's Pak In Chol. [caption id=attachment_298459 align=aligncenter width=1599] A meeting between Amarbayasgalan Dashzegve, chairman of the State Great Hural of Mongolia, and Woo Won-sik, speaker of the National Assembly of South Korea, July 30, 2025. Photo by Parliament of Mongolia.[/caption] Expressing pleasure at the follow-up meeting after Woo’s April 2025 visit to Mongolia, Amarbayasgalan emphasized South Korea’s importance as a key “Third Neighbor,” a Northeast Asian cooperation partner, and a shared advocate of democratic values. He put forward three core demands: resolving obstacles in the construction of central heating plants in 10 Mongolian provinces funded by South Korean concessional loans and overseeing the selection of new contractors; facilitating mutual people-to-people exchanges (including relaxing conditions for Mongolian citizens’ humanitarian travel to South Korea and addressing the issue of Mongolian citizens being repatriated at South Korean borders). In response, Woo pledged to promptly resume and advance the 10-province heating plant project, and stated that South Korea was exploring measures to facilitate Mongolian citizens’ travel, including introducing electronic visas, increasing consular staff at embassies, and simplifying visa procedures for group travel. The two sides also exchanged views on topics from previous official visits and reached a consensus to promote practical economic cooperation between the two countries. Following South Korea’s June presidential election, new President Lee Jae-myung tightened this linkage further. In a September call with Mongolian President Ukhnaa Khurelsukh, Lee proposed “accelerating EPA negotiations” and “promoting visa-free entry for Mongolian citizens” – one of Ulaanbaatar’s key demands, given that approximately 50,000 Mongolians work or study in South Korea, half of them illegally – in exchange for Mongolia’s support on the Korean Peninsula. South Korean Prime Minister Kim Min-seok later explicitly tied rare earth cooperation to regional tensions, urging Mongolia to “support our efforts to address regional instability.” Mongolian Deputy Prime Minister Nyam-Osor Uchral’s response was telling: he pledged to deepen critical minerals cooperation but avoided any mention of “neutrality,” exposing the diplomatic compromises behind economic dependence. Essentially, Mongolia was betting that Pyongyang would not sever ties because it needed ally support on the eve of the 80th anniversary of the Workers’ Party of Korea. This compromise thus achieved short-term risk management while securing economic rewards from Seoul – yet it carries significant long-term risks. Over-reliance on South Korea could distort the Third Neighbor Policy from diversification to dependence, ultimately eroding Mongolia’s diplomatic autonomy. The key to Mongolia’s escape from this dilemma lies in accelerating cooperation with other “third neighbors” such as the United States, Japan, and the European Union, ensuring economic pragmatism truly serves sovereignty rather than reducing Mongolia to a great power vassal. A Path Forward: Toward Principled Pragmatism To address internal and external challenges, Mongolia urgently needs to upgrade its strategic thinking – shifting from passive compromise to principled pragmatism, anchoring its foreign policy in sovereignty and core values to build a flexible, sustainable framework. This transformation must proceed in parallel in relations with both South and North Korea, while strengthening domestic institutional capacity. Mongolia must convert its resource advantages into substantive diplomatic leverage. In EPA negotiations, it should clarify two non-negotiable core demands: first, that South Korea sign a binding agreement prohibiting all intelligence activities on Mongolian territory, repairing the trust deficit caused by the KDIC spy scandal; second, that the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) take the lead in a defector processing mechanism, balancing humanitarian principles with sovereign security. Economically, Mongolia needs to move beyond the low-value-added “raw material exporter” model, promoting value-added cooperation in rare earth processing and smart manufacturing to nurture domestic industries. Reducing dependence on a single market and resource exports will reshape Mongolia from a resource supplier to an industrial partner – aligning with Seoul’s supply chain security interests while granting Ulaanbaatar economic initiative. Restoring trust with Pyongyang requires a shift from reactive to proactive diplomacy. First, Ulaanbaatar should use backchannel communications to address the interpreter defection candidly, reaffirming the principle of “non-interference in internal affairs,” echoing Ambassador Erdenedavaa’s 2024 commitment to “traditional friendly cooperation,” and clarifying that Mongolia will not become a tool to confront North Korea. Second, it should restart low-sensitivity cooperation projects – cultural exchanges, agricultural aid, and public health collaboration – avoiding contentious Korean Peninsula issues and repairing official trust through people-to-people interactions. Third, it should revive the “Ulaanbaatar Regional Forum on Denuclearization and Reconciliation on the Korean Peninsula,” proposed by Mongolia’s Foreign Ministry, positioning it as a nonconfrontational technical dialogue platform (focused on issues such as family reunions) to reactivate inter-Korean communication channels and revitalize its “bridge” value. Meanwhile, Mongolia can maintain its goodwill gesture of “not joining sanctions against North Korea” – a key bond in bilateral relations. The fundamental solution to the defector dilemma lies in establishing an institutionalized response mechanism. Supported by the UNHCR, this framework should include three core elements: clear asylum application criteria, strict confidential processing procedures, and third-country resettlement options. Such a system would safeguard the humanitarian rights of vulnerable groups while preventing individual incidents from escalating into diplomatic crises, translating the “humanitarian intermediary” vision of ”On the Way to the South” into actionable policy – and freeing Mongolia from the cycle of “passive response.” Conclusion Mongolia’s most valuable strategic asset is not its abundant mineral resources, but the trust recognized – or tolerated – by all stakeholders in the region, particularly Central Asia or the Korean Peninsula. This trust, forged over decades of balancing Seoul’s economic allure with Pyongyang’s demand for respect, represents the wisdom of transforming geographical vulnerability into diplomatic flexibility. Squandering this trust for short-term economic benefits or temporary appeasement of Pyongyang would inflict irreversible damage on Ulaanbaatar’s regional standing. For a nation that has turned vulnerability into flexibility for centuries, the current crisis is both a challenge and an opportunity for transformation. Mongolia must uphold principled pragmatism, maintaining a precise balance amid inter-Korean competition – avoiding becoming a tool of either side while refusing to abandon its core commitments to humanitarianism and sovereign dignity. Only then can its “neutral bridge” identity take root – safeguarding its own sovereignty, security, and development interests while contributing unique value to Northeast Asian stability, and establishing a model for medium, small-state diplomacy in an era of great power competition.