Copyright Star Tribune

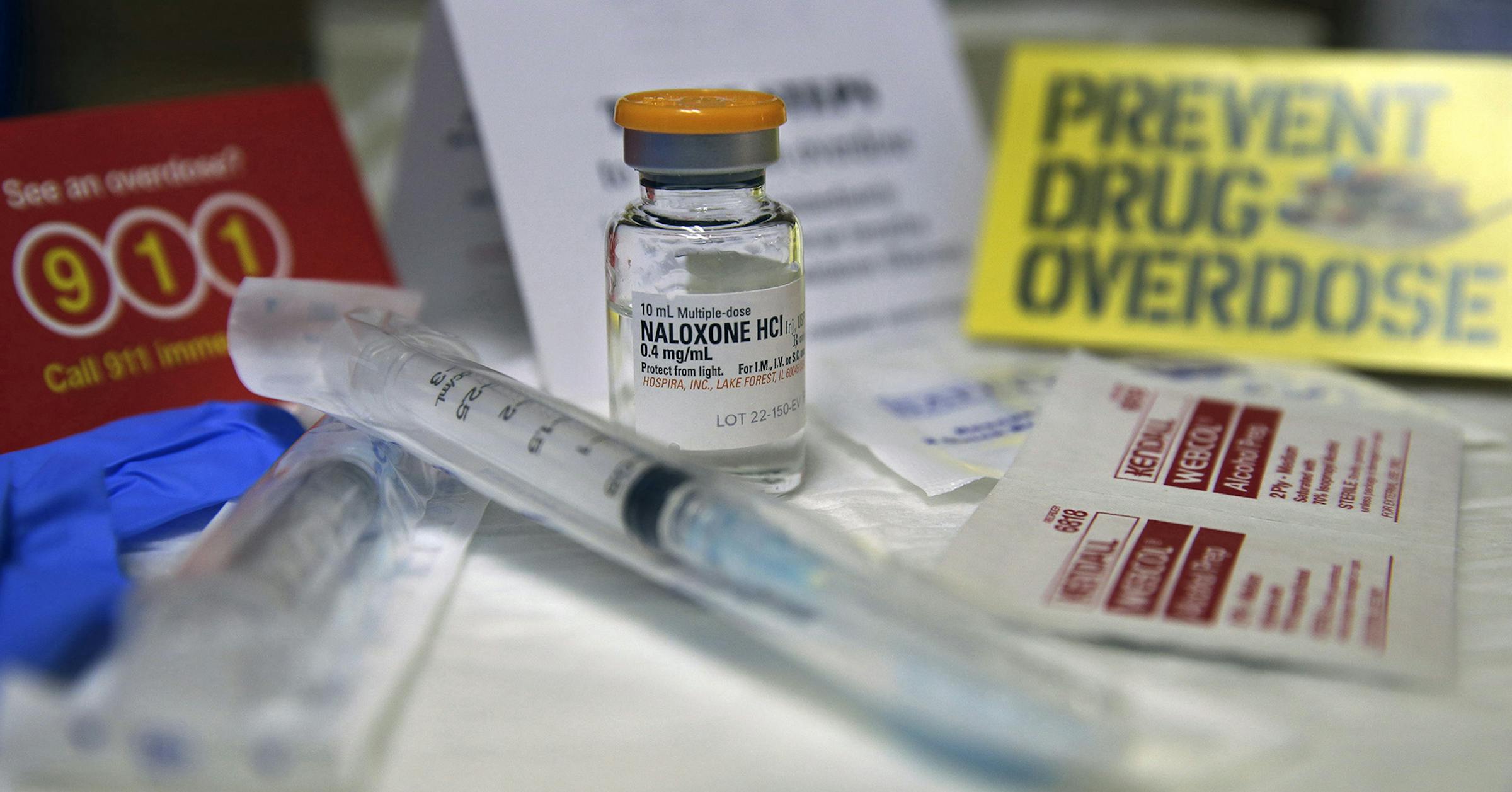

The 994 overdose deaths in 2024 still represent a concern for state health officials. There were only 639 such deaths in 2018, when the epidemic was exacerbated by widespread access to potent, synthetic opioids such as fentanyl. But the total has declined for two years in a row from a peak in 2022 of 1,392 deaths. Challenges remain. A new monthly snapshot tool shows Minnesota with no change in drug overdose deaths when comparing preliminary data from the first half of 2025 with the same timeframe last year. But the trend last year was so favorable that Gov. Tim Walz on Tuesday announced the annual data, which is usually released each fall by the Minnesota Department of Health. “This is measurable progress, and we’re going to keep working to save lives,” the governor said in a statement. Walz credited state investments over the past three years that broadened access beyond hospitals and clinics to naloxone, an overdose rescue drug, and increased addiction treatment and recovery services. Overdose deaths involving opioids declined across all categories — from illicit heroin and fentanyl to prescription painkillers such as oxycodone. Deaths involving stimulants and cocaine also declined, suggesting that the progress wasn’t merely a shift in the drug of choice among people who use them. Tribal leaders credited state-funded prevention strategies that were mindful of their culture and unique needs. American Indians make up less than 3% of Minnesota’s population, but almost 12% of its drug overdose deaths. “Even one life lost to overdose is too many, and the work must continue to ensure families and communities do not have to carry that loss,” Mariah Wabasha, director of Lower Sioux Human Services, said in a written statement accompanying the governor’s announcement. The opioid epidemic in Minnesota had its roots two decades ago in abuse or overuse of prescription painkillers, prompting a state crackdown on excessive prescribing and investments in alternative forms of pain management. As painkiller prescriptions declined, the use of illicit fentanyl emerged. The new risk was punctuated in 2016 by the death of music icon Prince, who had been dealing with chronic pain when he overdosed on counterfeit fentanyl pills that resembled prescription painkillers.