Copyright thehindu

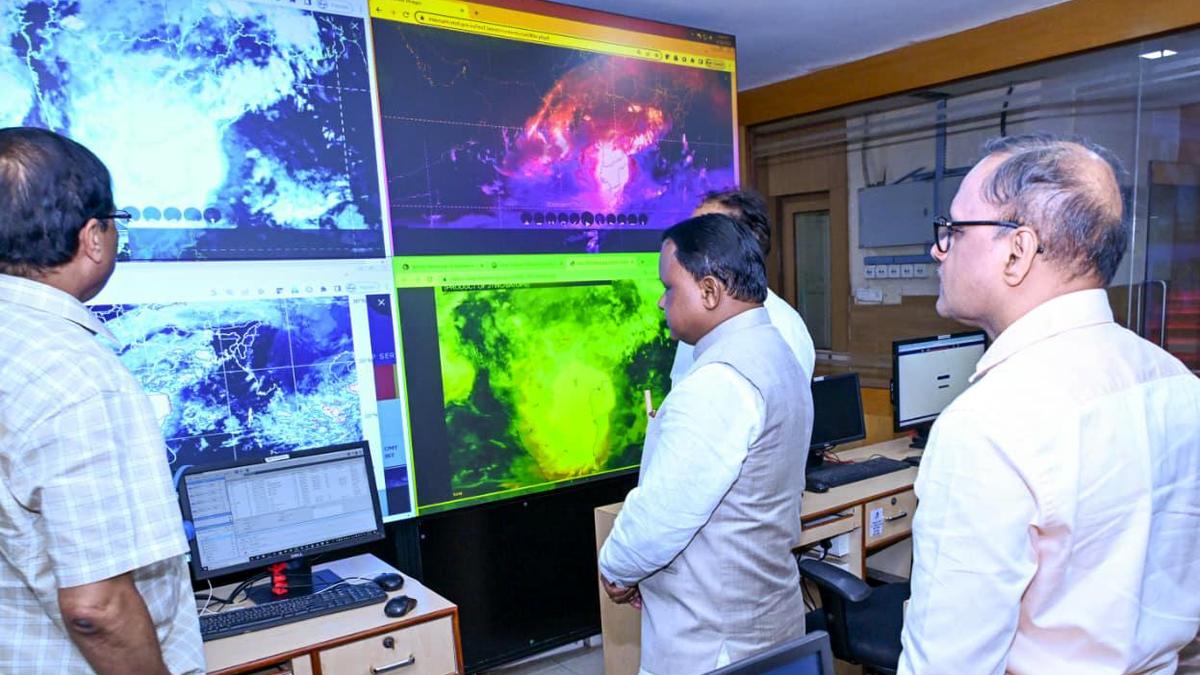

When Cyclone Montha struck the eastern coast on October 28, 2025, it repeated a grim pattern familiar to Odisha and its neighbours—flattening fields, flooding villages, and sending thousands into shelters. Making landfall between Machilipatnam and Kalingapatnam near Kakinada in Andhra Pradesh with winds of 100-110 kmph, the storm swept inland through southern Odisha’s Ganjam, Rayagada and Koraput districts and parts of Telangana before weakening into a depression. Early reports suggest extensive crop and horticultural losses across the region. The swift evacuation of thousands once again demonstrated Odisha’s preparedness, but the greater challenge now lies ahead—protecting livelihoods after the storm. Odisha’s vulnerability to tropical cyclones is structural, not accidental. Its 575-kilometre coastline lies in one of the world’s six most cyclone-prone regions. Over the past century, nearly 260 cyclones have struck the State—from the catastrophic 1999 super-cyclone to Phailin in 2013, Titli in 2018, Fani in 2019, and Yaas in 2021. Editorial | Relief, rehabilitation: On India’s east coast and cyclones Phailin alone caused losses of nearly ₹9,000 crore, with agriculture and livestock contributing more than a quarter of that amount. Counting fatalities alone thus misses the larger and more enduring costs of these disasters. The immediate economic shock is swift and devastating. Montha’s destruction will mean acute income losses for marginal farmers, cash-flow crises for traders, and food supply disruptions in nearby towns. After Cyclone Fani, a UNDP-led assessment estimated about ₹3,000 crore in damage to agriculture, livestock and fisheries, and nearly seven crore lost rural working days—roughly ₹2,700 crore in lost wages. The economic pain lingers long after the storm dissipates. Farmers still need to repay loans, buy seeds and fertilisers, and restore irrigation before the next season begins. Fishers must replace nets, boats and iceboxes well before any insurance claim materialises. Beyond these visible effects, the secondary slowdown is often more destructive. In storm-hit districts, informal businesses remain closed for months, credit tightens, and banks grow risk-averse. Public spending is diverted from development projects to reconstruction, delaying progress in health, education and infrastructure. Economists estimate that major cyclones can shave several percentage points off Odisha’s gross State Domestic Product in affected years. Over the past two decades, Odisha has transformed disaster management. The Odisha State Disaster Management Authority (OSDMA) has expanded cyclone shelters, strengthened early warnings, and institutionalised mass evacuations. The results are remarkable: the 1999 super-cyclone killed nearly 10,000 people; Phailin fewer than 50; and Yaas in 2021 only two. Yet this progress in saving lives has not been matched by livelihood recovery. Reconstruction still prioritises visible infrastructure such as roads, housing and power. Ecological pressures deepen the crisis. Storm surges and saltwater intrusion degrade fertile soils and wetlands, undermining the natural capital of smallholders and fishers. Rising seas prolong saline flooding, reducing yields and pushing farmers toward less profitable crops or migration. These shifts carry social costs—disrupted schooling, family separation, and weakening rural communities. Odisha’s next phase of resilience must prioritise livelihoods alongside lives. Crop and fishery insurance requires faster, simpler claims so producers can replant or rebuild quickly. Emergency credit and brief loan moratoria can avert distress sales. Expanding MGNREGS for rebuilding embankments and ponds can inject cash and restore assets. Equally vital is nature-based protection. Mangroves, wetlands and tidal buffers can cut wave energy by up to 90%, offering both ecological and livelihood security. Odisha’s UN-backed mangrove restoration and climate-smart aquaculture, from mud-crab farming to rice intensification, show how adaptation can sustain incomes. Financial systems must also adapt. A mix of contingency funds, regional insurance pools, flexible central transfers, and partnerships should channel resources directly to smallholders and coastal communities. The author teaches economics at ICFAI School of Social Sciences, IFHE. Views expressed are personal.