Copyright newsroom

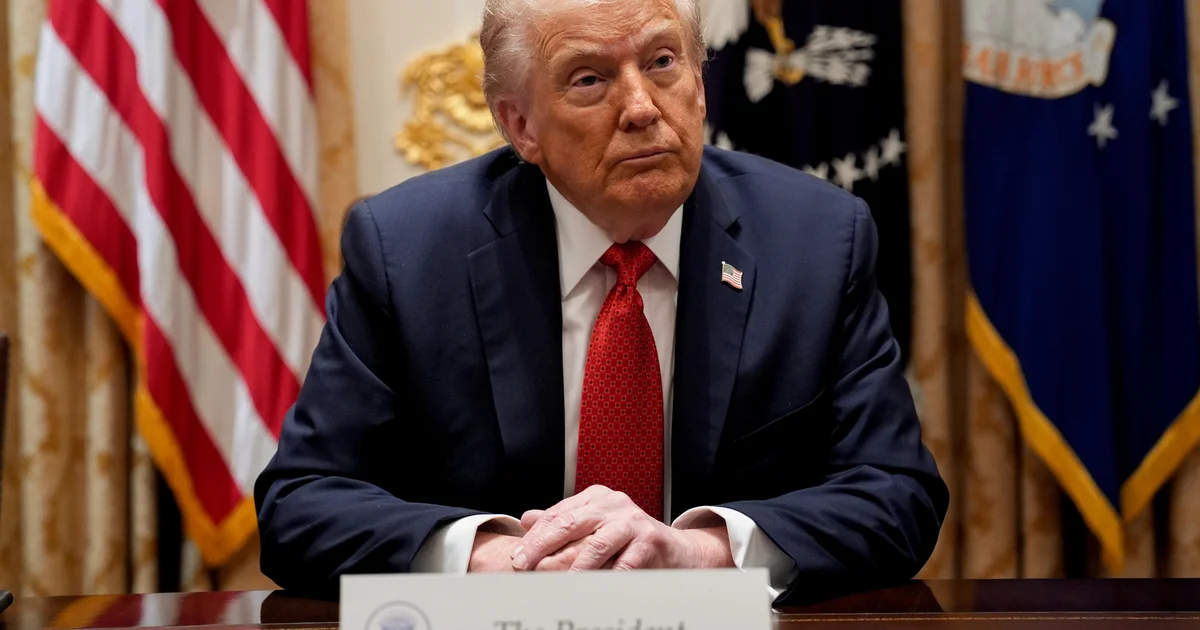

The media part of being prime minister never used to worry me. It was slightly different in a few respects, though. What we didn’t have in the 1990s was these quasi-interviews on the run into Parliament or while walking across to the Beehive. It certainly wasn’t common. I’m not sure who started it here. Perhaps they’re borrowing from Donald Trump, because Trump’s interviews now are nearly always done as he is getting into a helicopter or getting out of it. You could get a job over there as the new press secretary, David — they come and go, mind. It mightn’t be a permanent position. It’s difficult to pigeonhole what makes a good leader. In politics, what leaders have to be able to do is to give confidence to the caucus, plainly, and to the wider party. But also there’s the capacity to see the issues they should be fighting, debating, pursuing, promoting. Because that’s the main thing from the country’s perspective. The differences in style probably go to those who do their homework and those who get others to do homework. In other words, there’s planning in it. Rather than the “Well, I know I can bullshit my way through” sort of thing. Take Helen Clark. Helen was never a bombastic leader. It just wasn’t her style. She was a careful, thoughtful leader who normally kept the issues clear in her mind. She was quite controlling, I believe, in terms of her caucus, but it never appeared as if she tried to win an argument by brute personality or bombastic speeches alone. She brought her own style to the podium and to the leadership of the country, which again appeared to be about getting the facts, getting the detail, getting her team to produce the data, and then putting it out in a manner that was acceptable and understood. That’s what a modern society requires. Clark didn’t take big risks. She had a quite clear philosophical base, which was conservative left in most things other than social issues. That fits in reasonably happily with a high percentage of New Zealanders, so she was comfortable being in front of audiences. Of course, Helen grew up in a farming family in Te Pahu, not that far from where we farmed in the King Country. You say we both could have ended up in the other party? I think she’d disagree with that, and I’d disagree with that, too, but I can see what you’re saying. What we both did try to do was have a rational position on issues and not just an ideological position. We were both the children of farmers, who are a reasonably pragmatic bunch. They have to be. If you’re farming, you know you don’t control everything, most notably the weather and international prices, so you have to have these other skills to navigate the negatives from time to time. I think this kind of background inculcates a certain realism in what you can or can’t predict with great accuracy. In terms of Labour leaders, in positive terms, that’s Fraser, Savage and Clark. David Lange as prime minister certainly gave New Zealand profile, with his erudite defence of New Zealand’s anti-nuclear position in the Oxford Union debate. I said at the time all New Zealanders could be proud of the performance. I think historically that’s it. With Lange, you see a prime minister being almost entirely subsumed by Roger Douglas, changing his mind dramatically and embracing neoliberalism, and turning Labour Party policy on its head and embracing policy many saw as to the right of the National Party. And being proud to do so. There was such a chasm between what he said before that 1984 election and what he did afterwards, in particular his subservience to Douglas and his economic policies and pursuits before the 1987 financial crash brought it all to an end. Looking back, the Rogernomics era lasted little more than three years. Was there any similarity between the Lange–Douglas dynamic and my relationship with Ruth Richardson? Not at all. Yes, Ruth certainly had clear views on economics, but there was never the Roger Douglas dominance thing going on. Not at all. I first met Ruth when she was a legal counsel with Federated Farmers, so I knew who she was and welcomed her when she came into politics. She was, in general, strongly supportive of Rogernomics, which made life a little difficult because its author was on the other side of the House. She was a committed believer in the markets having the capacity to answer all issues; the government’s role was to facilitate the markets to deliver the best possible answer. I had a much more cynical — sceptical might be a better word — view on that philosophy. I still do. While the market is a powerful adjudicator, history has shown that the markets also leave out large parts of society, which in turn leads to a variety of unpleasant developments: for instance, the 1918 Bolshevik revolution in Russia. So Ruth and I weren’t fully in lockstep on political economic philosophy. Despite that, though, I thought the clarity of her thinking would be beneficial. That’s why I made her minister of finance, a role she held for three years and through which she introduced a rigour into economic debate that was certainly beneficial. Ruth had quite a lot of support in caucus. But her rigid views on a lot of matters weren’t conducive, in my mind, to working in a coalition relationship. Bill English I thought of as my heir apparent. He came in in 1990. I was impressed with his work ethic. He was so hard-working as a backbencher and had such a clear mind. He had the potential to go all the way. The heir apparent thing didn’t quite work that way, although he eventually got there, becoming prime minister for a short while, after a long and convoluted journey. But he always had that ability. People really saw it in the 2017 election, unlike the appalling (from a National Party point of view) 2002 election and then the troubled period that followed with Don Brash. Don came close to winning in 2005. He was ideological in most things, as has become more and more apparent. So it was to the good fortune of the National Party that John Key had been elected when he was, in 2002, and was there to step up and take the party forward for the next three terms from 2008. John had a successful time as leader and PM. If Bill had been able to put together a coalition after the 2017 election, I believe that a key focus of his term would have been to rethink how we deliver welfare support. Bill is someone who is capable of thinking outside the box. Jenny Shipley was a capable minister but I never saw her as my successor. Her tenure as leader was short and unsuccessful as she lost the next election by a big margin. My colleagues never told me exactly why they wanted to change the leader when they did, so I can’t really tell you with any certainty what it is they were seeking, why they wanted Jenny. But it didn’t work. I was overseas when the coup happened, at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Edinburgh, and then in Paris — the first official visit to Paris by a New Zealand prime minister — where I laid a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at the Arc de Triomphe after dark. I don’t recall why we were so late. After my official duties were completed we set off for home with no inkling of the plotting that had been going on in Wellington while we were away. It has always surprised me that no one called and gave me a heads up on the plotting. When we landed in Auckland and came in through arrivals I saw my good friend Doug Graham there to meet me. He said we needed to talk. We moved away a little while the bags were being sorted and he gave me the lowdown on what was happening. He said that they were confident they had the numbers. I thought it was a huge mistake, obviously. But it wasn’t just ego. I knew as much as anyone that it was going to be hard to win the next election, to win a fourth term. The plotters claimed they had the numbers. Maybe so. I had one or two colleagues, especially Paul East, a perceptive friend and ministerial colleague, saying “Well, we should test that, Jim.” And I thought, “No, bugger it.” I was tired. I’d just come back from the other side of the world. I’d been working hard for the party for years. If that’s what they do when I’m out of the country, I thought, I’ll leave them to run it themselves and see how good they are. John Key was interesting. He had a natural, easy, welcoming persona. He played that leadership role well. He reached across divides. He had a soft word on most issues. He led New Zealand through some difficult times, including the financial crash of 2008 and the terrible Christchurch earthquakes. His departure a year before the triennial election was a surprise to me. Clearly he’d decided that he’d had enough of it. His was a short career in politics — short, successful and at the top. I suppose, if you can do that, then that’s the way to go. I think his decision to move out on his own terms showed careful thinking about his future and what he wanted to do. You can’t hold that against him. The party was less than impressed for a while, because they knew he was a major selling point. But this time, Bill English, unlike in 2002, stepped up and performed exceptionally well in the election. Unfortunately, for him, the mathematics of MMP said it wasn’t enough. The National Party is always looking to where its coalition partner might be in the future. I think it should be with the Greens, but it would take some time to see whether the Greens would be interested. After the last election I appointed myself to reach out to a few senior people in the Green Party. Some were interested, but the majority weren’t. That’s a pity because I believe a National–Green coalition would be good for New Zealand. In honour of the passing of Jim Bolger, this edited chapter is taken with kind permission from the fascinating portrait Fridays with Jim: Conversations about our country (Massey University Press, 2020), drawn from David Cohen’s conversations with the former PM every Friday for six months. David Cohen’s keenly anticipated new book Jacinda: The Untold Stories (Centrist Publishing, $39.99), a biography of Jacina Ardern written with Rebecca Keillor, will be published on November 10. “Pre-sales have been excellent,” he reports. As below, an exclusive first published image of the quite peculiar cover; and beneath that, the contents page, with some quite arresting chapter headings.