Copyright The Boston Globe

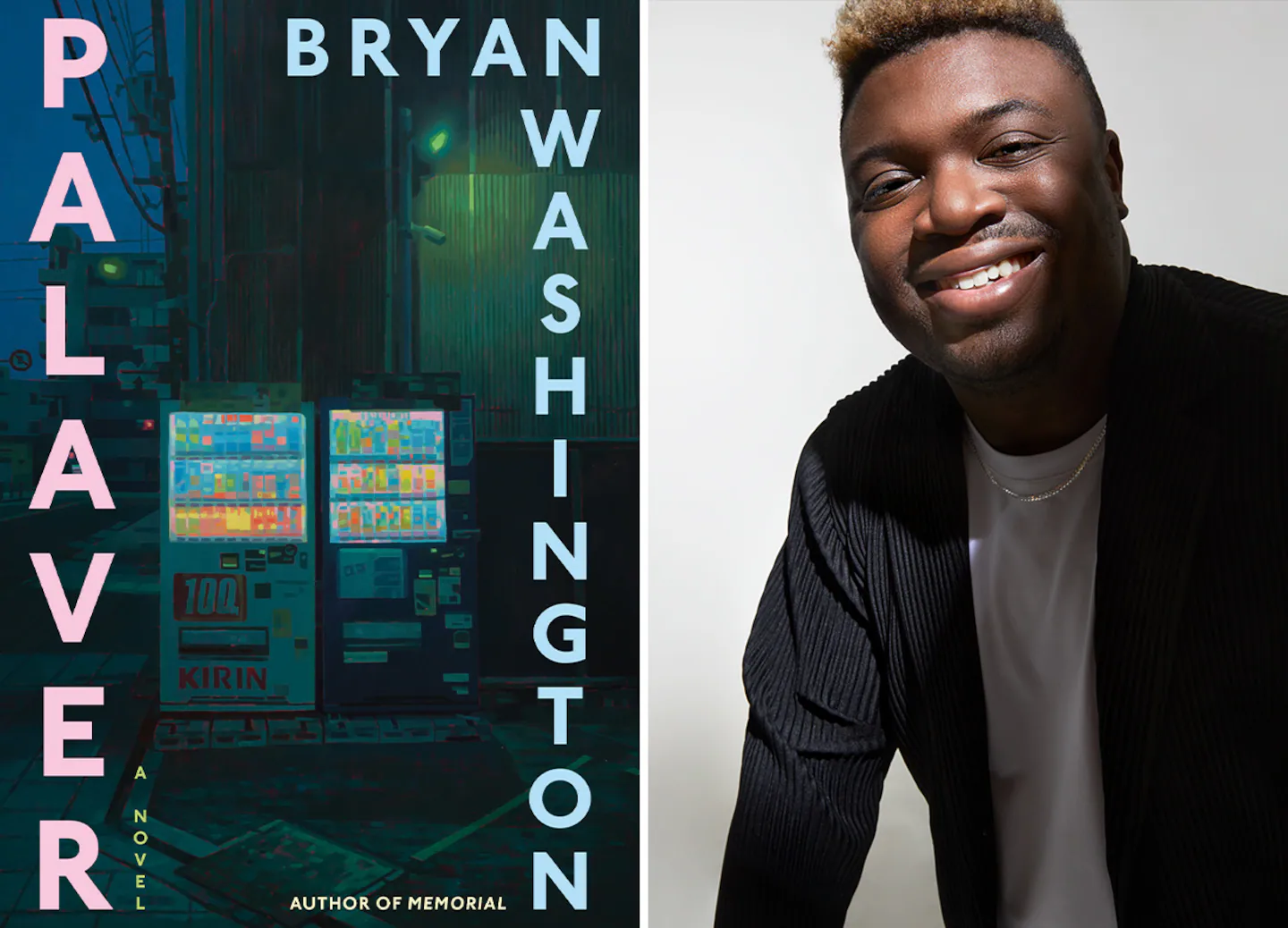

You don’t sound fine. Don’t tell me how I sound. That’s better. You’re breathing heavy. Have you been running? I’m fat. Fat people breathe heavy. Okay, said the mother. Let’s try this then. Are you safe?What time is it there? I’m fine, said the son. It’s four in the morning in Tokyo. Did something happen? No. Without further discussion and certainly with no invitation, she shows up on his doorstep not long after, and many more conversations like this, abrupt, snarky, at cross purposes, oblique and opaque, will ensue. As a noun, the word palaver refers to “an improvised conference between two groups, typically those without a shared language or culture;” as a verb it means “to talk unproductively and at length.” Both apply here, as the mother and the son spend two strained weeks together, talking but never quite communicating. Both are unwilling to actually try to reconnect, and both are constantly tripping over the shoals of their past. The brother, Chris, is in prison for drug dealing and the son absolutely refuses to talk about that. Physical abuse in the son’s past is referred to but not described or discussed, ever. The mother lost her brother in Jamaica to AIDS; if this has something to do with her feelings about her son’s sexuality, she doesn’t want to talk about that. The son certainly does not want to talk about his relationships with a married man or with his vibrant, bar-based friend group, and when the mother makes her own friend, a restaurateur in the neighborhood, the son will not hear a word about it. Similarly, letters are written but never mailed; letters received are never opened. So, yes, there’s a lot of palaver. Fortunately, there’s a kitten named Taro who occasionally elicits gentler emotions. While all the interpersonal relationships in “Palaver” are marked by withholding to some degree, the novel, which is a finalist for the National Book Award in fiction, is permeated by a deep affection for the city of Tokyo, its cuisine, its mass transit, its look and feel. The chapters are punctuated by sets of three or four black and white photographs of the city taken by the author, often showing the overlay of the personal and domestic on the geometry of the urban: lighted windows and potted plants, electric lines and lettered signs against all those quadrilaterals. And the food! The unpretentious way Washington writes about food is a throughline in his work, from “Lot” to “Memorial” to “Family Meal.” Somehow his simple menu descriptions are enough to incite ravenous hunger: “Eventually, one of them set a plate of papaya salad in front of the mother. It was followed by a tin of green curry, a plate of fried sardines, a crisped oyster omelet drowning in herbs, two bowls of rice, and a tiny dish of pickles.” All I can say is, let’s go to Tokyo right now. Even more fundamental to the son’s existence is the life and humor of the bar scene. “Arty Farty’s open till three, said Fumi, grinning.” Arty Farty is a real bar in ni-chōme, as is AISOTOPE; also mentioned are King Tokyo — “No offense to the crew, said Fumi, but this doesn’t feel like a King kind of night” — and others. “So the son made his way to Shinjuku, drinking his way through DaiDai, the first bar he slinked into. Then he walked to PORT. And Happy Ends. And Fumi’s Tavern. He stumbled through both Eagles, drinking some more.” Aside from possibly providing a handy to-do list for visitors to ni-chōme (some of the places may be fictional, or have changed names), the catalog of bars gives a sense of how the son spends his nights in Shinjuku, between days of mobile English lessons with a regular rota of clients. Sometimes, he doesn’t go home at all. “This time, the son paid for a love hotel, tucked beside the hundreds of gay bars stacked alongside it.” This lifestyle is defended by the son’s trans friend Alan, the half-Chinese owner of his favorite bar, a place “no bigger than a tiny coffee shop” appropriately called Friendly. Alan, who is awaiting top surgery, assures the son that he is part of a real chosen family. “We’re there for each other, said Alan. We’re all we have. Me, you, and the rest. We’re here, and then we’re gone, but we can be here for each other. It’s the least we can do, and also the hardest thing we can do. Because we don’t have to save the world, you know? Just show up for yourself, and for your people. That’s a good life.” Not much happens in “Palaver,” though by the mother’s departure, we see that things will be a little less arctic in the son’s family of origin going forward. It’s enough, at least enough for the reader who appreciates texture and delicacy, queer authenticity, and a well-placed crisped oyster. Marion Winik is the author of “First Comes Love” and “The Big Book of the Dead,” and the host of the NPR podcast, The Weekly Reader. Palaver By Bryan Washington Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 336 pages, $28