Copyright The New York Times

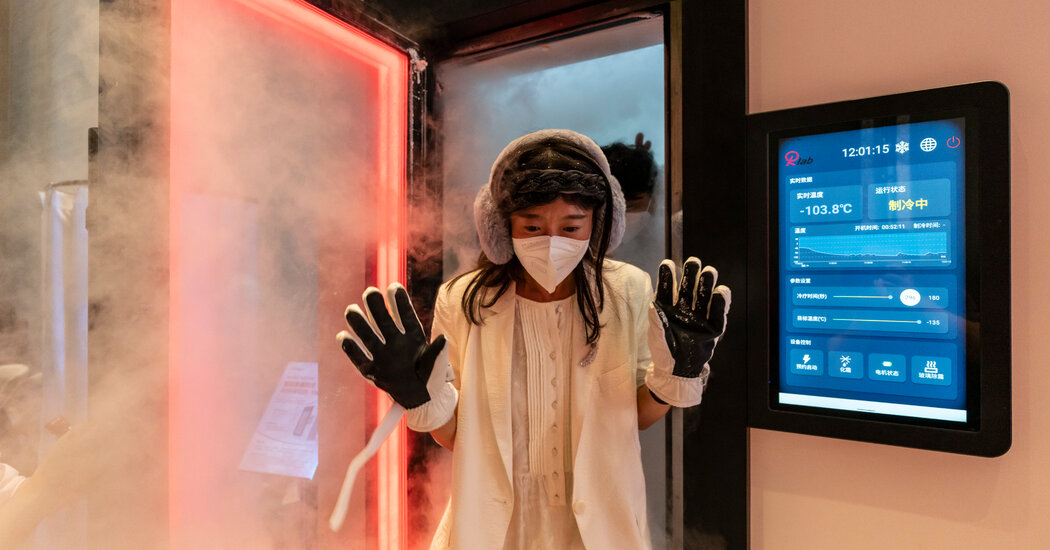

When a Chinese state television microphone recently caught China’s top leader, Xi Jinping, and President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia musing about the possibility of living to 150 and perhaps even forever, many eyebrows were raised. But there has been no tut-tutting in the laboratory of Lonvi Biosciences, a longevity medicine start-up in the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen. “Living to 150 is definitely realistic,” said Lyu Qinghua, the chief technology officer of the company, which has developed anti-aging pills based on a compound found in grapeseed extract. “In a few years, this will be the reality.” He is skeptical about modern medicine defeating death entirely — something Mr. Putin said was possible with organ transplants — but he thinks that longevity science is advancing so fast even the seemingly impossible might come to pass. “In five to 10 years, nobody will get cancer,” he predicted. The search for the elixir of life, embraced with gusto in recent years by American tech billionaires like Peter Thiel, has been underway in China for more than two millenniums. It started with the first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, who ordered a nationwide hunt for death-defying potions. Just in case that did not work, he also ordered the creation of thousands of terra-cotta warriors to protect him in his grave should he die. A whiff of quackery has hung over the longevity business from the start. But investment from the state and private companies, as well as surging interest among both Chinese leaders and the public, have turned it into a legitimate and sometimes lucrative branch of medicine. China, eager to catch up with and, whenever possible, surpass the West in biotech, artificial intelligence and other advanced technologies, has made the longevity industry a national priority, pouring billions into research and related commercial spinoffs. “They have improved very rapidly. A few years ago, there was nothing here and the West was still far ahead,” said Vadim Gladyshev, a Harvard Medical School professor who has done pioneering work on longevity, including an experiment that extended the expected life span of old mice by connecting their circulatory systems to young mice. Chinese researchers, he said during a recent trip to China to attend two scientific conferences, “are rapidly catching up.” China’s average life expectancy last year reached 79 years, five years higher than the global average, according to The People’s Daily, the Communist Party’s mouthpiece. But that, achieved through steady improvements in health care and lifestyle, is still behind Japan’s average of nearly 85 years and a long way from the 150 years mentioned by Mr. Xi. Mr. Xi and Mr. Putin, both 72, may have just been making small talk. But they were taken seriously by exiled opponents of the Communist Party, who pointed to a 2019 video that appeared on Chinese social media purporting to be a promotional pitch by an elite military hospital in Beijing, 301, which treats senior officials. The video, which was quickly scrubbed by Chinese censors, boasted that the hospital was doing pioneering work for the “981 Leaders’ Health Project” — and aimed to extend the life span of senior party figures to 150 years. “The average life span of Chinese leaders is far longer than the life span of leaders in developed nations,” the video said, pointing to decades of work by the hospital to keep alive leaders like Mao Zedong, who died at 82 in 1976, and Deng Xiaoping, who was 92 when he died in 1997. Sensitive to all discussion of leaders’ health, Chinese state television, which inadvertently captured the conversation between the leaders before a military parade in Beijing in September, ordered Western news services to delete the footage. The hot-mic musings aside, China’s enthusiasm for extending life-span has grown in tandem with its rapid economic growth, which has given hundreds of millions of people the time and money needed to look beyond surviving day-to-day. One Chinese company riding the tide has been Time Pie, a Shanghai-based group that got its start marketing dietary supplements and now organizes scientific conferences and publishes a magazine, Aging Slow, Living Well. “Nobody in China was talking about longevity before, only rich Americans,” said Gan Yu, the company’s co-founder. “Now many Chinese are interested and have the money they need to extend their lives.” Surging interest was on display at a recent international gathering organized by Time Pie in Shanghai of Chinese and foreign scientists presenting their research, as well as businesses hawking anti-aging creams and potions, goji berries, cryogenic and hyperbaric chambers and other devices that are supposed to slow aging. Rlab, a Shanghai-based company that claims “technology can prevent humans from aging,” invited prospective customers to enter what looked like a telephone booth — a cryogenic device in which the temperature drops to minus 200 Fahrenheit. Ivor Yu, an entrepreneur from northeast China in the longevity business, stepped in, only to jump out after a few seconds, shivering from the cold. He also inspected the company’s “anti-aging magic box.” He left without buying. SuperiorMed, a health care company that runs what it says is the world’s biggest “longevity hospital” in the Chinese city of Chengdu, promoted “immortality islands,” though it acknowledged they do not exist yet. The company’s founder, Li Dale, was vague about whether “immortality islands” would be anything more than luxury health spas offering blood tests and other forms of preventive medicine in exotic locales. But the conference also attracted serious scientists like Harvard’s Prof. Gladyshev and Steve Horvath, a German American aging researcher who is a legend in the field for his work developing the first “aging clock,” a measure of aging biomarkers. Longevity science, Mr. Horvath said, used to be dominated by “wild claims” that alienated many legitimate scientists, but has seen a “vast improvement” in recent years, including in China. “Nobody serious talks about immortality at scientific conferences anymore because it is so absurd,” he added. But the idea of living forever lingers as a marketing tool. Immortal Dragons, a Singapore investment fund focused on longevity projects, is run by a young entrepreneur from China, Bo Yang Wang, who has explored moneymaking opportunities in cryopreservation, 3-D printing of organs and “whole-body replacement.” Lonvi, the longevity start-up in Shenzhen, has more modest goals. It opened a lab in 2022 in a business tower on the edge of the sprawling Chinese city next to Hong Kong after scientists in Shanghai discovered that a natural compound found in grapeseed extract — procyanidin C1 or PCC1 — increased the life span of mice by selectively killing senescent, or aged, cells and protecting healthy cells. (Lonvi is not connected to the Shanghai scientists.) Mice treated with the compound lived 9.4 percent longer across their lifetime — and 64.2 percent longer from the start of treatment. The findings, published in an article in Nature Metabolism in 2021, were groundbreaking. But in September, the journal issued an editor’s note alerting readers to “errors in the data,” though it did not retract the article. Subsequent studies, including one in Japan, have supported the initial claims. Translating what works for mice to human beings requires long and rigorous testing, and what works for mice often disappoints with people, said David Barzilai, an American medical doctor and founder of Barzilai Longevity Consulting. The “canonical example” of this, he said, is rapamycin, a compound that has been proven to “robustly” extend the life span of mice and other animals but has “uncertain” effect on healthy human adults. China, he said, “is increasingly taking longevity and aging biology seriously at both the institutional and policy level.” But, he added, “strong scientific intent does not guarantee uniformly high rigor or translational success. The challenge is not just doing more, but doing better.”