Copyright Mechanicsburg Patriot News

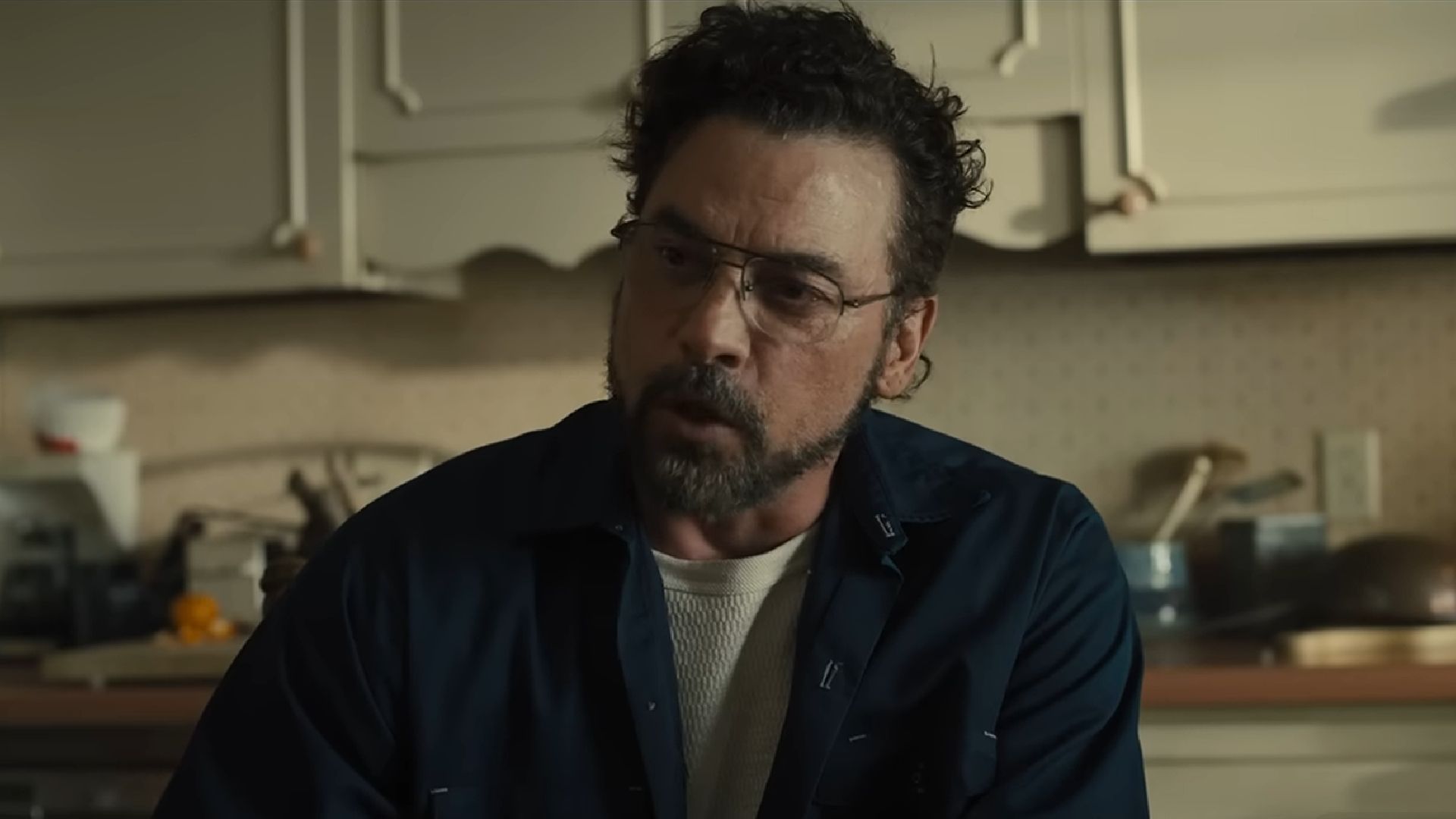

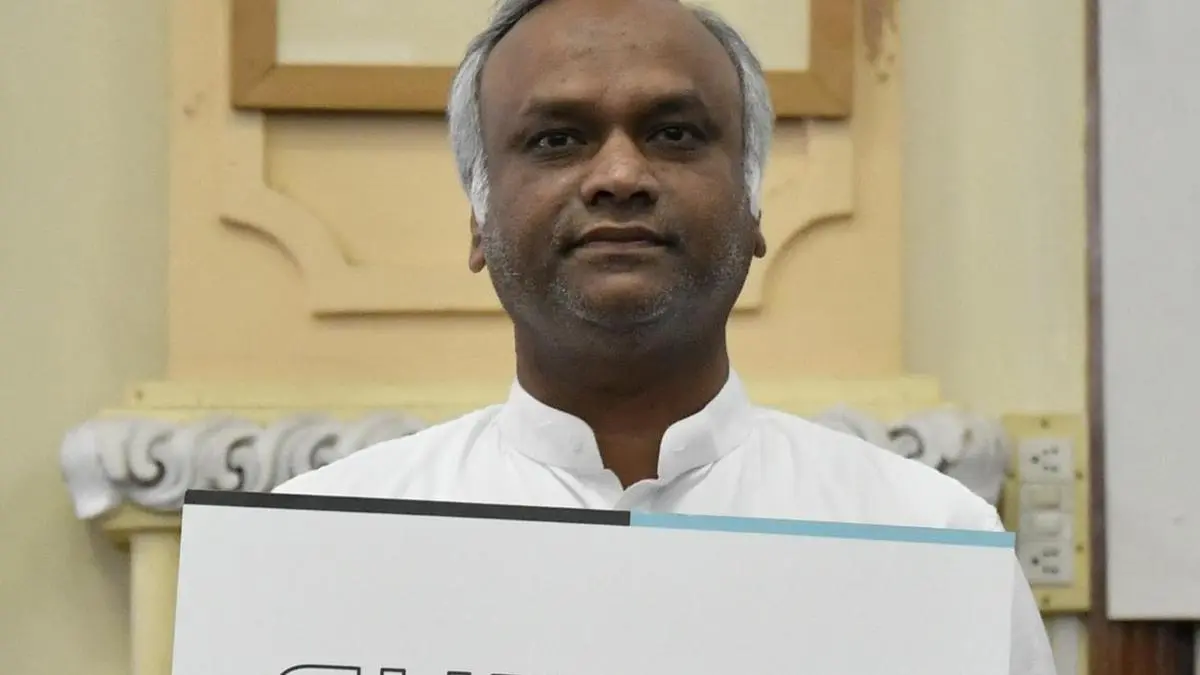

Editor’s note: This is the sixth story in a series titled “Virtual Dominance: How a cyber charter school has upended K-12 education in Pa.” The series investigates the causes and consequences of the unprecedented growth of Commonwealth Charter Academy–Pa.’s fastest growing school. Commonwealth Charter Academy, Pa.’s fastest growing school, rarely has public participation during its board of trustees meetings, according to former employees and more than eight years worth of meeting minutes. A handful of CCA parents tried to participate during three board meetings three years ago but CCA’s board interrupted the parents during public comments, denigrated their concerns and ultimately told them to choose a different school if they continued to criticize the school’s choices. After the board’s regular business during the meeting in February of 2022, one parent used her three minutes of public comment to list off changes she wanted to see in how the board operates. “Like meetings move to a time when more parents and staff can attend,” she said. “Recorded meetings for those who cannot attend in person. Email blasts for special or emergency meetings. Accurate contact information for the board members and maybe a simplified way to bring suggestions or concerns to the board for consideration.” The parent, who attended via Zoom, mentioned some of the board members had been hard to hear through the microphone. And then she criticized the school’s decision to excuse CCA’s senior administrators before public comments. “There are two of us speaking today,” she said. “That would be six minutes. And it was kind of rude to say that we’d be wasting their time.” Although her three minutes were not yet over, Ralph Dyer, the president of the board at the time, interrupted her and dismissed her concerns. Dyer said he considered it one of the school’s strengths that the board isn’t elected and doesn’t have to be as responsive to the public. “This permits CCA to create and implement long-term plans, which are not possible in traditional districts due to the disruptive two-year election cycles that are prone to generating discontent and personal agendas,” Dyer had written to the parent in a letter. Dyer accused the parent of bringing up issues she had previously brought to the board’s attention. But when the parent pointed out several of her suggestions were new, Dyer interrupted again. “Okay but they’re superficial,” he said. “They’re not superficial,” she said. “I can’t hear.” Dyer told her not to come back to another meeting if she was just going to repeat herself. “Be very careful next time,” he said. “Either accept where we’re going or find another school.” CCA declined to respond to questions about the board meeting in question and instead attacked PennLive for reporting on it. “You have received overwhelmingly positive comments about CCA, its leadership, and the Board of Trustees,” said Tim Eller, a spokesperson for CCA, despite PennLive’s recent report in which the majority of CCA’s staff who spoke to PennLive had serious concerns with how fast the school is growing. “But instead, you seek out a few disgruntled individuals from years ago.” Melissa Melewsky, a lawyer for the Pennsylvania NewsMedia Association, said the CCA board members who dismissed the parent’s concerns, “paints a stark picture of the board’s view on the importance of public participation.” Melewsky believes public school boards should investigate and address issues that might limit the public’s ability to hear during meetings. “A public meeting is not a formality intended to function only as a window into the school board’s votes; the public meeting is the public’s opportunity to have a voice in the decision-making process,” Melewsky said. “The board doesn’t have to agree with every speaker, but they do have to listen and provide a meaningful opportunity for public input.” Among the least transparent CCA’s leaders say they work hard to make their parents happy and keep them enrolled at the school–and PennLive found evidence this is working. But this focus on parents doesn’t seem to apply to participation in the school’s governance. A PennLive analysis found CCA makes it harder for its parents and other members of the public to participate in board meetings than similar cyber and traditional schools. And in the few instances when parents have tried to weigh in, the parents said CCA seemed to be actively discouraging their input. PennLive looked at eight different aspects of transparency and found CCA’s board was less transparent than most of its much smaller cyber school peers–and significantly less transparent than Pittsburgh Public Schools, the traditional district with the most similar enrollment. This is reflected in how few members of the public participate in CCA’s meetings. In 2024, the board heard from one CCA family, one school choice supporter and one cyber school critic, all year. At Pittsburgh Public Schools, by contrast, two to three dozen people raised issues to the board every month. In 2023, not a single person spoke during CCA’s public comments all year. Public participation was such an afterthought that CCA’s meeting minutes often didn’t mention the public had a chance to speak. CCA says it goes out of its way to seek feedback in other, non-public forums. “CCA’s administration and Board engage students, families, and the broader CCA community through events, meetings, and advisory panels,” Eller said. “These forums provide meaningful opportunities for students, parents, and staff to share feedback that directly influences programs, policies, and operations.” Most of Pa’s. 14 cyber charter schools post a link to their meetings, so anyone can attend remotely, since most families don’t live near where the meeting is taking place. CCA is one of only three cyber schools that requires the public to request a link to the meeting ahead of time if they want to attend. (Eller said this is for increased “security.”) CCA is one of only a handful of cyber schools that hold their board meetings during the school day, when many employees have difficulty attending. John Lipchik, who retired from CCA after 12 years as a history teacher there in 2023, said he got the impression the school didn’t want staff to come to meetings because they were scheduled when people were teaching. “Who’s available at 9 a.m.? Whether you’re working or taking care of little kids or whatever you’re doing?” he said. “No one’s available then.” During the only CCA board meeting that drew a large crowd in recent memory—a special meeting to vote on whether to fire the school’s top academic officer—staff reported CCA’s administrators were monitoring the Zoom meeting to see if any staff were present who should be working. Eller, CCA’s spokesperson, said no matter what time the board meeting is at, “it will be inconvenient for someone.” Eller didn’t specify for whom the current meetings are convenient. But in a 2022 letter to a parent, Dyer stated plainly that it wasn’t parents or teachers. “The time and day of board meetings are determined to best suit the busy schedules of the Trustees and key staff members whose attendance is vital,” Dyer wrote. CCA’s choice to prioritize senior leadership and board members over the public is “highly unusual,” according to Kevin Busher, the chief advocacy officer for the Pennsylvania School Boards Association. “Most of our school districts’ school boards are operating after 5 o’clock,” he said. “It’s very odd to have an open board meeting or even a committee meeting during school hours.” Pittsburgh Public Schools holds multiple committee meetings per month for its board to address the complicated issues facing such a large district. But CCA, by contrast, doesn’t hold any public committee meetings to dive more deeply into the issues facing the school. CCA says this promotes more accountability and engagement because every one of its trustees is “equally informed and involved in all aspects of governance,” rather than having board members divided up onto different committees. “Committees often bog down organizations in redundant processes, excessive meetings, and bureaucratic inefficiencies that distract from what truly matters – the education of students,” said Eller, CCA’s spokesperson. Insight PA Cyber Charter, which enrolls less than a tenth as many students as CCA, holds multiple board committee meetings, including about the school’s governance, finances, academics and community engagement. Eileen Cannistraci, who was serving as the CEO of Insight until earlier this month, said she had pushed for committee meetings because they make the board more involved in the school’s decisions–and does it in a way the public can see. “We can really focus on particular items,” she said. Every cyber charter school posts the minutes of past board meetings, but CCA posts only the most recent three years–fewer than all but one other cyber charter school. CCA continually looks at these policies and practices, said Eller, its spokesperson, “to ensure they remain clear, compliant, and reflective of best practices.” Even when the meeting minutes are available, it’s difficult to find out what the board is voting on because CCA doesn’t post information about the contracts, rules and policies up for discussion. In August the school made this even more difficult by requiring the public to make a records in order to obtain the school’s detailed financial reports. A spokesperson for CCA said the school can’t redact its financial reports before meetings because the school’s finances have become more complicated. Six of Pa.’s smaller cyber charter schools, on the other hand, post detailed information about their policies and contracts under consideration. “We just want to be transparent. We want to be open,” said Rich Jensen, the CEO of Agora Cyber Charter, which has posted nine years of detailed information about its board’s decisions, including video recordings of every meeting. “We’re a public school. We just want to make sure that we are just being open to anyone that is interested in that type of information. And I can’t really speak to why others might not.” ‘He was definitely a bully’ Kevin Shivers, a former board member at CCA, said another issue that impacts the transparency of CCA’s board meetings is that its meetings are rarely covered by local media. ‘Nobody. Never,” Shivers said. “I always found that extraordinary.” Marcie Mulligan, another former CCA board member, said she would sometimes invite the press but they didn’t show up. “There’s times that they’re discussing money for advertising and money for programs and whether or not to fund certain things,” she said. “And I think the public needs to know where some of that is going” Nevertheless, Mulligan said, the board didn’t just rubber stamp the administration’s proposals and sometimes had vigorous debates about what was being voted on. But as the school grew larger, she said, the mood shifted. “Towards the end, I was kind of alone often in how I voted,” she said. Mulligan said Dyer, the former board president, was sometimes condescending and dismissive of her concerns when she didn’t vote how he wanted her to. “He was definitely a bully,” she said. In particular, when issues came up regarding compensation for CCA’s executive leadership team, Mulligan said, Dyer would get angry if anyone brought up questions about approving their full compensation packages. CCA defended Dyer’s leadership, saying he helped push the school’s board through major transitions that helped the school grow into the educational juggernaut it has become. (Dyer died from cancer in 2024.) And the school defended Dyer’s approach to running board meetings. “Mr. Dyer respectfully exercised his prerogative as board chairman, fulfilling his duty to maintain order and decorum during public meetings in accordance with established school policy and parliamentary procedure,” Eller said. Dyer isn’t the only board member that parents have complained about. During a special board meeting in November of 2021, a CCA parent complained that the current board president and former Pa. Senator, Jeffrey Piccola, was looking at his phone during public comments. ”There’s some of you that don’t even look like you care what parents are saying,” the parent said. Instead of apologizing for being momentarily distracted—Piccola attacked the parent for bringing it up. “I was responding to a family situation,” Piccola said. “So any aspersions cast on this member of the board or any member of the board that we are not paying attention is strictly not true.” Two months later Piccola’s lawyer threatened legal action against a different parent who raised questions about Piccola’s fitness to serve on the board after she learned that Piccola had been publicly reprimanded by the state Supreme Court’s disciplinary board in 2012 for a conflict of interest ethics violation in his law practice. (Piccola was reprimanded because he didn’t disclose to families he represented that he was also representing an “heir-hunting firm” that was trying to secure a portion of their inheritances.) Piccola’s lawyers told the CCA parent that his ethics violation didn’t constitute a felony, and so it was wrong for her to question his fitness to serve on CCA’s board. “On behalf of Senator Piccola,” his lawyer said in a letter to the parent. “we are demanding that you immediately and publicly retract these statements and issue a public apology.” ‘Order and decorum’ After the first parent’s concerns about CCA’s board were shot down by Dyer at the February 2022 meeting, a second parent was allowed to speak. “I’m a little afraid to talk to you now after the way that you just talked to the last parent,” the parent started off. She began raising concerns about some of the new material included in the school’s curriculum. “Let me stop you right there and I don’t mean to be rude, but I’m going to stop you,” Dyer said. The parent should have brought up her concerns to the school’s CEO rather than the board, he told her. The parent, whose voice had already been wobbly began to break down, half sobbing. “It’s okay for you to talk over me but I can’t talk over you?” The parent then asked Tom Longenecker, the CEO, if he agreed with Dyer. Longenecker said he did. The parent pressed again, asking whether Longenecker agreed with how Dyer was speaking to her and Longenecker declined to intercede. “You’re addressing the board,” Longenecker said. Dyer then brought an end to the public comments—one of the last times a parent has spoken at a CCA board meeting. CCA didn’t respond to a question about whether a parent ever brought up a concern at a board meeting that the board thought was legitimate and took to heart. “You have choices. We are a school of choice,” Dyer said as the meeting came to an end. “We have a school to run.”