Copyright forbes

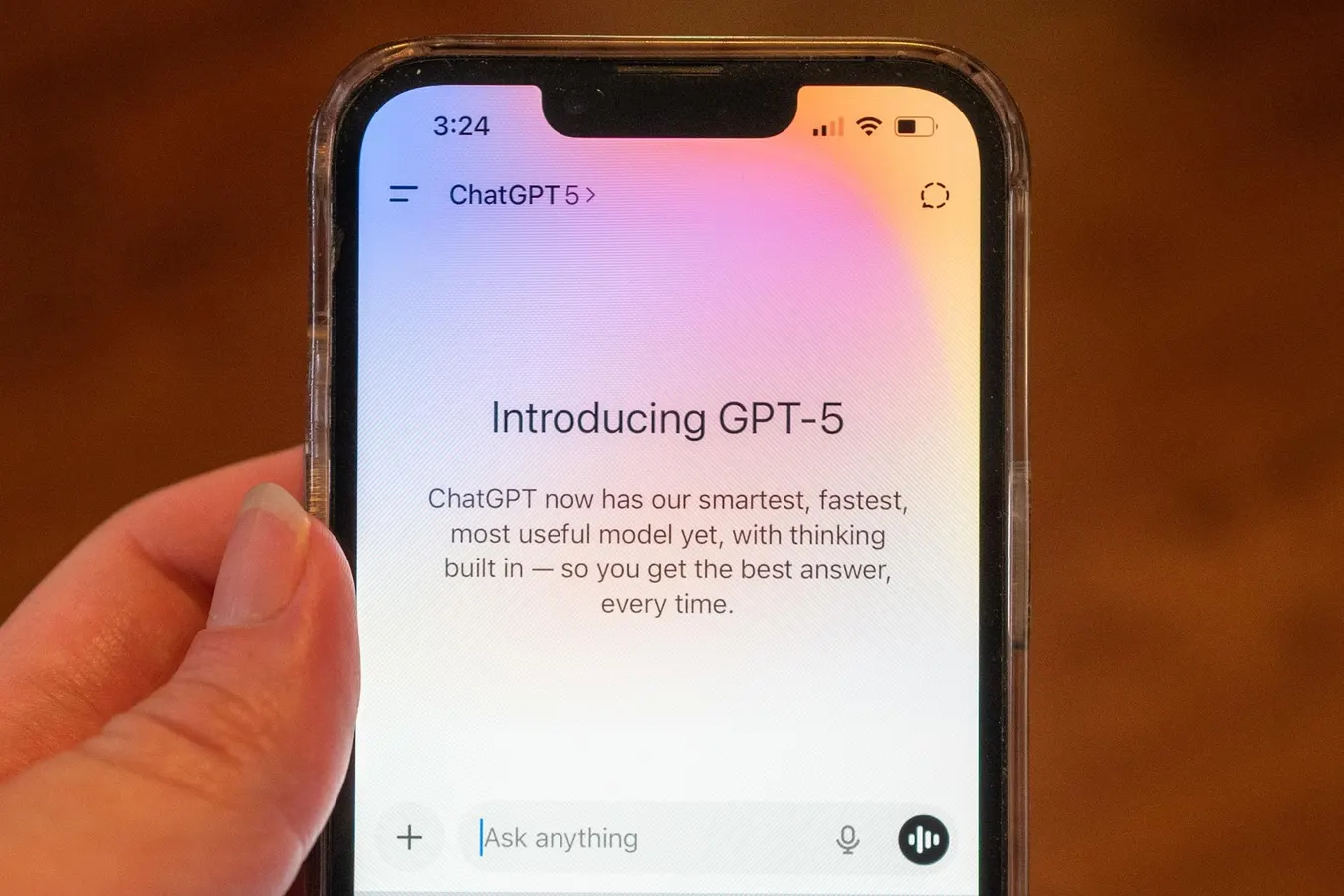

It’s hard being a patient. In 2006, I received a diagnosis that decimated my outlook on life. This was followed by a second opinion that revived it with an entirely different diagnosis and treatment plan. I felt betrayed and misled by the first so-called specialist who was quick to deliver life-altering news with minimal evidentiary support. I later felt vindicated when I finally understood my diagnosis, appreciated the imaging, and had a plan moving forward. I wish back then I had a sophisticated search engine, online community, or ChatGPT that could at least pretend to be a seemingly unbiased arbiter of my symptoms. Close-up of a person's hand using the OpenAI GPT-5 artificial intelligence model on an iPhone, with text introducing the model, Lafayette, California, August 7, 2025. (Photo by Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images) Gado via Getty Images The title “doctor” translates to “teacher,” as a sign of respect for the role physicians play in education and guidance. In the late 1700s, we saw “doctor” assume a new connotation as charlatans emerged, sacrificing quality for consumerism. Just a few years after a global pandemic ravaged frontline medical personnel, we’ve seen the stock of physicians plummet. In a recent Gallup Poll of Americans, trust in doctors has sharply declined from 77% in 2020 to 53% in 2025, the lowest in 30 years. Now we see history repeating itself - only this time under the guise of patient empowerment from unsupervised technology offering unrestricted medical advice. Boston, MA - February 6: A protester holds a sign up reading honor your Hippocratic oath so that healthcare workers inside Brigham and Womens Hospital can see it outside of Brigham and Womens Hospital in Boston on Feb. 6, 2022. People protest the hospitals reported refusal to perform a heart transplant on a patient named DJ Ferguson who wont get vaccinated against COVID-19. (Photo by Jessica Rinaldi/The Boston Globe via Getty Images) Boston Globe via Getty Images The Hippocratic Oath was once a basic tripartite contract between the patient, doctor, and disease. But today, this simple arrangement is complicated by the assimilation of health insurance, a third-payer system, malpractice liability, industry influence, and federal regulation. While the “red tape” surrounding the Oath is a well-documented consequence of the continued corporate castration of medicine, the impact of opening the digital floodgates on doctors is underappreciated. The role of newer technologies offering unprecedented, instantaneous access has been celebrated as a “digital democracy” through the equalizing Internet of Things. Specifically, we laud patient portals, mobile messaging apps, HIPAA-compliant emails, search engines, doctor-rating sites, social media, and AI models because - from the patient perspective - it offers at least partial insight into a highly confusing system with zero transparency. It’s easy to see why some insight is more appealing than no insight for a patient already in a state of immense personal vulnerability. When compared to the opacity that leads to appointments that can’t be scheduled for months, medication refills that can’t be readily fulfilled, phone trees that go nowhere, and voicemails that remain unreturned, can we really blame the patient (our “rationale consumer”) for turning to the immediacy of digital solutions? MORE FOR YOU This digital democracy has been celebrated for both logistical advantages and for eliminating “physician paternalism,” thereby enabling patient empowerment and autonomy. Importantly, it helps patients avoid scenarios like my first opinion where I received a misdiagnosis and unclear treatment plan. Digital cues can be excellent when paired with physician oversight. However, when our healthcare system strands patients to the point that partial insight from Google search, ChatGPT responses, Reddit threads, and Facebook groups becomes their primary window into their own health, the outfall can be more dangerous than no insight whatsoever. The digital era has allowed content, particularly around health and medicine, to be produced en masse from trustworthy and untrustworthy sources alike. These platforms prioritize speed over accuracy. These algorithms are primed to affirm, not challenge, our belief system. Most concerning, there is little to no regulation online. Unlike television or print ads, few online are reminding you to “ask your doctor if this may be right for you.” People once implicitly understood the concept of not believing everything they see on the Internet. Unfortunately, that ship has sailed. Doctors now see online suggestions supersede their own. Despite clear postoperative instructions, I will have one or two patients every year choose to follow an ACL reconstruction protocol from TikTok or Instagram over my own tailored to the operation I performed. These patients no longer sheepishly hide or deny this, and will directly ask “well, why does this reel say otherwise?” Having to review social medial footage and clarify that this video was for an entirely different operation and an entirely different set of circumstances is increasingly common - but defeating. This phenomenon occurs in older populations as well, who increasingly find not just community in Facebook groups but also prescriptive advice that often contradict my own and may result in self-inflicted harm when taken out of context. Doctors now see online narratives trickle into the office. No narrative is more compelling than blaming “rich, greedy” doctors for the broken healthcare system, even though just 5-7% of healthcare services represent physician fees. In an otherwise faceless system, physicians make easy scapegoats. But if money was truly the only goal, all doctors acknowledge there exist far more peaceful and lucrative life choices than medicine. Nonetheless, patients are not shy to point out the perceived greed of physicians often enough that it almost feels hardwired. Just recently, when I extended a hand to conclude the visit, the patient reflexively joked doctors “always have their hand out, don’t they?” This was followed up with another patient who came to see me for a failed knee preservation surgery elsewhere. He was upset at the previous four opinions for requesting in-office x-rays, which he refused all four times because he had an MRI. I took this as a personal challenge to be the one doctor who would reach him with education. I genuinely believed by the end of my explanation, he’d be the one asking for the x-ray to better understand why his prior surgery failed. The patient again refused because “all you doctors care about is gouging my insurance with x-rays.” There exists a segment of the population simply unwilling to accept new information despite education and redirection. Changing preconceptions is difficult, especially when one already believes the messenger is compromised. Doctors now manage unrealistic, glamorized online expectations more than ever. I recently had a patient fly from another state to ask me if I would fracture both her leg bones, rotate them, and re-fix them just to improve the aesthetics of her calves. It was disheartening to learn this suggestion arrived to her from the comment section of an influencer’s post, which was later confirmed by an AI chatbot as a reasonable request. I had another patient see me for a third opinion after undergoing two prior hamstring tendon repair surgeries to the same leg after the first repair failed. Although he had minimal pain and was back to running at age 68, the leg didn’t feel quite the same as it once did before the injury. He earnestly asked me to surgically open both legs, use the uninjured leg as a side-by-side reference to the twice operated leg, and sew the musculature back to identically replicate an anatomic diagram he found on Google Images. Another patient came to see me after a hip replacement in Mexico six weeks prior. He had pus coming out of the thigh, could no longer stand from pain, but would only attempt surgery after trying $35,000 worth of PRP because they saw a few patients on Facebook who had their hip pain “cured” with this stem cell treatment. For each above encounter, my time spent educating and counseling certainly left each patient unfulfilled and disappointed. While many patients are able to understand the risks and benefits of their decision from their doctor, I have found unregulated digital content works both ways: sometimes it serves the patient, but other times it backfires badly. “The customer is always right” in business, and while healthcare may be a business, doctoring is not. Patients may derive a sense of increased autonomy to choose their own path with the digital democracy (as is their right), but physicians remain unflaggingly stalwart and responsible for their well-being in the face of online misinformation, depersonalization, and disconnection. Herein lies the contradiction of doctoring in the digital era: although as doctors we are expected to dutifully keep patients from harm by teaching and healing, we are increasingly failing to meet their expectations of blind affirmation, unrealistic perfectionism, and unfettered immediacy that the digital world routinely offers. The reality is that this silent digital heavyweight perennially accompanies and influences patients more than a doctor visit ever could. It’s tempting and understandable to doctor-shop like an Amazon Prime member, read Google reviews like a product label, diagnose our diseases from ChatGPT, derive expectations from Reddit threads, and doom scroll TikTok for tips. It’s easy to argue that the digital democracy may have spared me from my hapless first opinion where I left with more questions than answers. But it’s far more important to remember that the second opinion only restored my health and faith after experiencing the compassion, conviction, and connection of a doctor who sat and took the time. If our healthcare ecosystem was meant to run on digital signals in an era where we’ve never been more connected, why do we feel more disconnected than ever? Would you rather medicine be personal and driven by expertise - or corporate and driven by affirmation? An unchecked digital democracy in healthcare where we remain unreceptive to “ask your doctor if this may be right for you” threatens the very existence of doctoring as a “teacher.” Every time we inevitably fail to re-affirm digital misconceptions, we risk sacrificing our net promoter score for a clean conscience. The further we move from face-to-face encounters, the more siloed we become. The more cameos we invite to the Hippocratic Oath, the more confused we become. The more we devalue the nuanced art of doctoring, the faster we replace physicians with disconnected checkout clerks tailored to healthcare consumerism. Contrary to what others will have you believe, the “business model” and “digital ecosystem” of healthcare will always rely on human connection. Trusting a stranger with a scalpel to fix you is as personal as it gets. There will never be an online proxy or go-to-market strategy that substitutes for the humbling gravity of this responsibility because everything outside the patient, the doctor, and the disease is just digital noise. Editorial StandardsReprints & Permissions