Copyright Slate

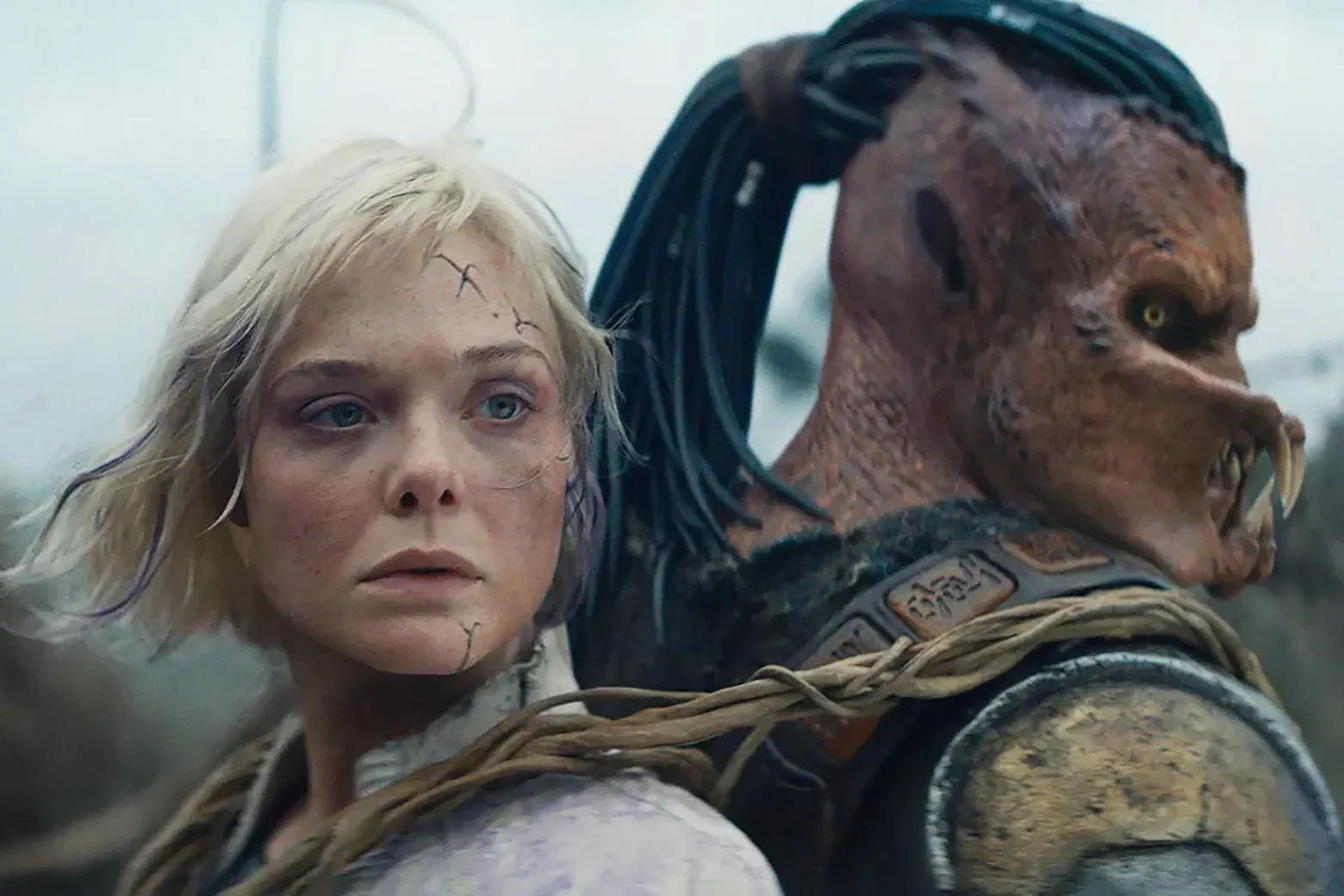

Predator: Badlands, the newest entry into the 38-year-old franchise and the third Predator movie directed by Dan Trachtenberg, is a PG-13 story about a young Predator alien named Dek, who’s rejected by his father for being a runt. The story, as in many Predator movies over the years, is about a less-powerful warrior overcoming inherent disadvantage to prevail over enemies. But in this case, it’s a Yautja—in other words, one of the Predators himself—who’s doing it, not a special forces guy, an LAPD officer, a mercenary who used to be a special forces guy, or a former Army Ranger. (There are, in fact, no special forces guys at all in this one, or in either of the other Trachtenberg Predator films, 2022’s Prey or 2025’s animated anthology, Predator: Killer of Killers—a feat.) Partway through, you see that Badlands is also an Alien movie, but there’s no xenomorph—just the top half of a curious and sweet synthetic human, made by the Weyland-Yutani corporation and named Thia (Elle Fanning)—and characters from the two franchises will work together, instead of battling one another. In the attention to detail in the design of the flora and fauna of the alien planet where it takes place—where Dek ventures to try to kill a fearsome, invincible creature known as the Kalisk and to prove himself to his father—Badlands is reminiscent of James Cameron’s Avatar movies. Its script can be funny, with little moments that made my screening laugh out loud, as when the planet is revealed to be so over-the-top dangerous that even casually tossing away a tiny, cute-looking caterpillar reveals that the little critter detonates like a grenade when threatened. It’s not very gory—there are dismemberments and decapitations, but all of them happen to aliens or synthetic humans, which means that no humans are harmed, and not even an ounce in all of the buckets of blood is red. Even the traditional spine-rip goes kawaii, when the baby alien Bud, whose scenes provide a lot of the film’s comic relief, does it in imitation of his Yautja hero. Yes, this is the first Predator you can safely bring a reasonably attentive elementary-aged child to view. But these are not the only ways that Badlands is rethinking the Predator formula. That’s because Badlands is also the movie that proves it: Dan Trachtenberg is turning the Predator franchise feminist. If you had told me in 2021, before Trachtenberg’s first Predator movie came out, that there would be a series of Predator films that would be animated by a critique of brute force as a way of life, I wouldn’t have believed it. But viewers of the other two Trachtenberg installments might not find Badlands’ rather socially progressive message—Dek must give up on the Yautja way of doing everything by himself, learn the value of diverse contributions to a team, and come to think of himself not just as a predator but as a protector—so surprising. Prey, which was released streaming-only on Hulu, was set in 1719, and featured a scrappy Comanche heroine, Naru, played by Amber Midthunder. Naru wants to prove herself as a hunter, so she goes out after the Yautja who has come to her territory to battle bears, mountain lions, and wolves, and eventually defeats it, using bravery as well as her superior knowledge of the ins and outs of the terrain. The presence of Naru marks a difference from the previous Predator movies, whose would-be “final girls” were all men with a background in the military or law enforcement, and with little to no motivation beyond “escape the Predator.” But the mere existence of a heroine is not the only way that Prey pries at the macho ideal. The non-Yautja villains of Prey—a band of French trappers, desperately in need of baths and dentistry—believe themselves dominant and unkillable. They’re colonizers and exploiters of the land, who skin a field of buffalo and use no other part of the animals, and who capture Naru and her fellow Comanche and put them in cages. They serve as fine fodder for a splendid array of Predator kills. (The moment in Prey when a trio of trappers, having fired their puny muskets at the Yautja, desperately fumble to reload offers a zing of humor that foreshadows Badlands’ light tone.) Upon its release in 2022, so much attention was paid to the fact that it featured a historic, full Comanche translation (as well as the fact that it, quite simply, ruled) that little notice was paid to the ways in which it was also tweaking the usual action-movie machismo. Killer of Killers, the animated anthology that Trachtenberg dropped on Hulu this summer, does something similar. It begins with three chapters that each follow a warrior who kills a Yautja in his or her own time: a female Viking, a ninja, and a World War II Navy fighter pilot. But in its fourth and final chapter, the Yautja have captured each of these champions and placed them in a cryogenic sleep, where an alien master of ceremonies pits them against one another in gladiatorial combat. Instead of fighting one another, the three of them learn to overcome language barriers and mutual suspicion to help one another. Although Killer of Killers doesn’t have as direct a critique of brute force as Prey, in its three very different combatants learning how to stop being lone wolves, you can see an early version of the trio of Dek, Thia, and Bud in Badlands. As Thia puts it to Dek, “The alpha isn’t the wolf who kills the most. He is the one who best protects the pack.” Yes, it was a good idea to put this IP in the hands of someone who understood that the story of the Yautja as infinitely powerful warriors was ripe for a little bit of deconstruction. If the Alien franchise is for the philosophers and the academics, with its existential musings on the nature of humanity and its dark vision of capitalism’s future, the Predator franchise used to be for us action lunkheads who just wanted to see a generous helping of gruesome slaughter. The Yautja, aliens who have advanced weapons technology and have solved the problem of space travel, have been, up until Badlands, philosophically simple: Might makes right, or, as one Yautja puts it in Badlands, “Sensitivity is weakness.” There was, in hindsight, a lot of room to play. You might be able to guess that Badlands made a few people mad online over the weekend, given how fans of heritage IP can get. And yes, you can search up jokes about how the movie is “Predator: Muppet Babies” and sarcastic takes on the idea of a queer Predator. (There isn’t really much reason to believe that this Predator is gay, but that didn’t stop Hollywood Reporter critic Richard Lawson from joking, approvingly, that he might be, and thereby setting off that whole firestorm.) But while the right wing loves to suggest that if you “go woke,” you “go broke,” Predator: Badlands did just great at the box office this past weekend—in fact, way better than expected, with the franchise’s best opening yet, and a near-perfect A-minus rating from audiences. I don’t think audiences go to Predator movies for their politics, and I don’t think this one is any exception, but I do think that, decades in, every franchise needs to find a way to mix things up, and Trachtenberg has done it.