Copyright The New York Times

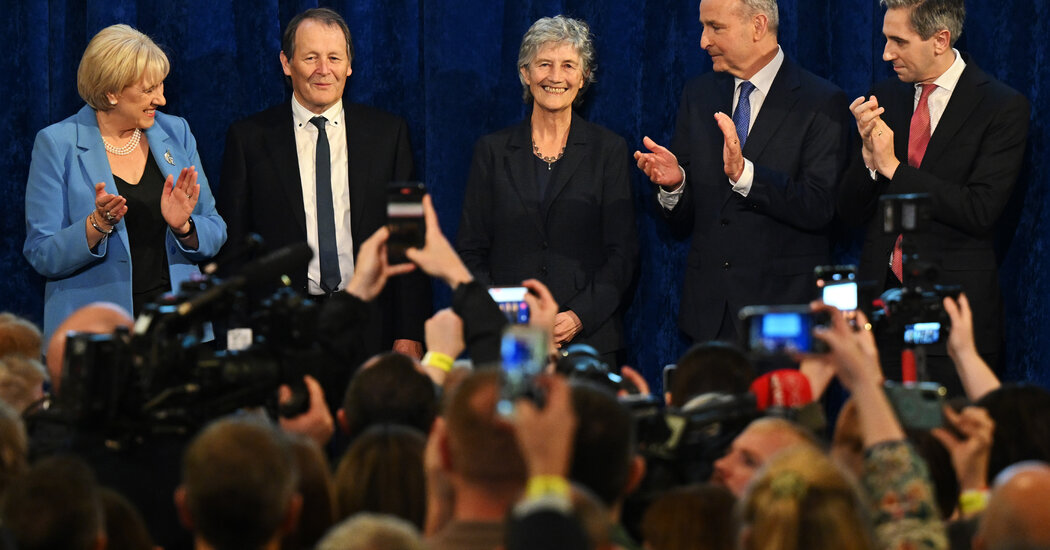

She has said Ireland’s policy of neutrality is threatened “by the warmongering military industrial complex” in much of Europe. She predicted that a “united Ireland is inevitable.” She declared that in war-torn Gaza, Israel’s “genocide was enabled and resourced by American money.” Such blunt, unfiltered comments have made Catherine Connolly something of an outlier in Irish politics. They also helped get her elected last week as the president of Ireland, winning the largest popular mandate of any candidate since the presidency, a largely ceremonial post, was created in 1937. A left-wing lawyer and political independent, Ms. Connolly, 68, capitalized on the same anti-establishment fervor in the electorate, and enthusiasm among younger voters, that is propelling Zohran Mamdani, the 34-year-old democratic socialist who is the front-runner to be the next mayor of New York City. As Ms. Connolly prepares to take office, the question teasing Ireland’s political establishment is whether she will push the envelope further than Mr. Higgins, who became more outspoken in his later years, occasionally clashing with the government on economic and social justice issues. “This is someone who is to the left of anyone we’ve ever had in high office in Ireland,” said Daniel Mulhall, a former Irish ambassador to the United States. “One shouldn’t ignore the fact that voters were willing to elect someone whose views are beyond the political mainstream.” He compared her with Senator Bernie Sanders, independent of Vermont, or Jeremy Corbyn, the former Labour Party leader in Britain, and noted that her victory was getting attention from the American left. She got a glowing message of congratulations from Representative Ilhan Omar, the Democrat and progressive leader from Minnesota. Some of Ms. Connolly’s success, Mr. Mulhall said, was thanks to her impassioned support of Palestinian civilians in Gaza. Many in Ireland sympathize with the Palestinians because of what they view as a shared history of colonial repression and the trauma of a long sectarian conflict. Ireland’s decades of strife, known as the Troubles, were finally settled in the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. Ireland was early among European countries in recognizing a Palestinian state. After it decided to join a genocide case brought by South Africa against Israel at the International Court of Justice, Israel closed its embassy in Dublin, citing the “extreme anti-Israel policy of the Irish government.” During a televised campaign debate, Ms. Connolly was asked whether she would confront President Trump over American military support for Israel. She deflected the question, saying it was unlikely to come up in a meeting with Mr. Trump, which she said would be little more than a meet-and-greet. “If the discussion was genocide,” she added, “that’s a completely different thing, but I doubt that would be the discussion.” Ms. Connolly also faced questions about a visit she and other Irish lawmakers made to Syria in 2018. The delegation visited a Palestinian refugee camp near the capital, Damascus, and the shattered city of Aleppo. Critics said they were hosted by Syrians with ties to the government of the ousted president, Bashar al-Assad. Ms. Connolly said she had always condemned Mr. Assad. While Mr. Mulhall and other analysts said they doubted that Ms. Connolly’s views on Gaza would become much of a headache for Ireland, her views about Irish foreign and military policy were another matter. “Her main complaint is that the current government is abandoning the notion of Irish neutrality” at a time when other European countries are rearming themselves to hedge against a disengaging United States, said Diarmaid Ferriter, a professor of modern Irish history at University College Dublin. The government — a grand coalition of Ireland’s two main center-right parties, Fine Gael and Fianna Fail — is committed to legislation that would make it easier to deploy Irish troops in peacekeeping missions by removing the need for the United Nations to approve such missions. It would fall to Ms. Connolly as president to sign such a law or refer it to the Supreme Court if she concluded it was unconstitutional. She is not beholden to any party, having quit the left-wing Labour Party in 2007 after it refused to add her to an election ticket for Parliament alongside Mr. Higgins. In some ways, Ms. Connolly’s victory was a fluke. The expected front-runner, Mairead McGuinness, a former European Union commissioner, opted not to run because of health concerns. Jim Gavin, a former Gaelic football player put forward by Fianna Fail, pulled out 19 days before the election over a financial scandal. “We ended up with just two candidates on the ballot, which is really unusual in an Irish election,” said Theresa Reidy, a professor of politics at University College Cork. “The voters were immensely dissatisfied by the confluence of events that produced this constrained choice.” While there was certainly protest voting, Ms. Connolly was an adroit candidate, particularly on social media. A video on social media of her kicking a soccer ball and keeping it in the air went viral, showcasing her athletic talents.