Copyright cbc

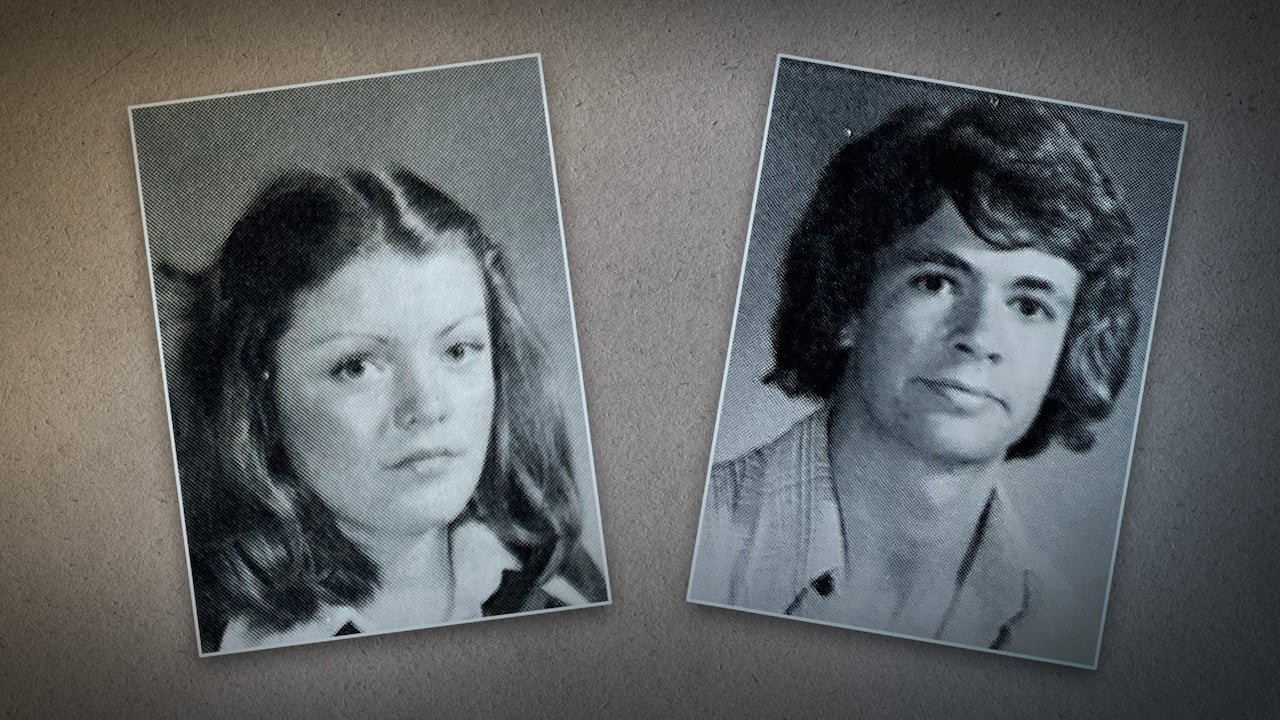

He killed two people, wounded several others and left the rest of us scarred with wounds hard to heal. I was 15 and in Grade 11, sitting in a nearby classroom. I remember the sound of broken glass, shouts of “shooter on the loose” and everyone running in panic, some with blood on their clothes. The awful tragedy happened years ago — long over but not yet ended for me and so many others. This is the nature of trauma, I suppose: buried, but somehow still alive. In October 1975, Robert Poulin, an-18-year-old student, lured another student, 17-year-old Kim Rabot, to his basement bedroom where he raped and murdered her, then set his room on fire. He then packed a sawed-off shotgun into a duffle bag and rode his bicycle to his school, St. Pius X High School, on Fisher Avenue in Ottawa. Once there, he fired a number of shots in Classroom 71, his Grade 13 religion class — one of which would eventually kill 18-year-old Mark Hough, a month later. He then backed up into the hallway taking his own life with the same gun. Deadly school shootings in Canada The next day, the school administrator's approach — viewed through my present-day eyes — was undeniably wrong. There was no school closure or an official period of mourning. Instead, there was a mass to comfort and remind us of the school’s motto: To establish all things in Christ. I felt numb but I wanted to be with my friends and classmates — hoping it would ease the heaviness of the trauma. Then classes proceeded, even in No. 71, which overnight had been partially patched and “disinfected” with a smell that lives with me today — perhaps the administration thought it could bleach away the horror. Sitting in that class, it was impossible not to imagine the gun blasts, screams of terror and the wounded bleeding. I remember my teacher, the much-admired Father Bedard. His complexion was grey, his speech forgivably incoherent given what he lived through the day before. Many students I later spoke to who were there that day regret that in the aftermath there was little, if any, opportunity to talk about our grief, anger and the muddle of feelings we had no name for. For me, it just remained stuck somewhere inside. What of our lives since then? After graduation, I went on to report on Ottawa's stories for decades at CBC News, where I worked alongside senior broadcast technologist, Pierre Millette. He was a survivor of that religion class. Only once in that time did we bring up the shooting. It was cursory so neither of us got upset. Yet, more recently, I learned the storehouse of haunting memories was there. Over the last six months, we’ve spoken about the shooting a dozen times — both of us sharing details we’d never spoken before to anyone. It was so long after the tragedy but I could finally vent my feelings with someone who wanted the same. Each time we spoke I felt a swell of relief. Sitting almost behind the classroom door, Millette told me the barrel of the gun was about half a metre from his face. That left me chilled. When Poulin stopped firing, Millette recalled jumping from his desk and slamming the door. He also remembers smashing a classroom window so classmates could escape. I told Pierre my trauma wasn’t experiencing what he lived through but simply imagining it. And the “ifs” he had pondered about how it could have unfolded differently. Millette was sitting right beside Mark Hough when the bullets strayed by. He wasn’t hit but that doesn't mean there was no harm. At first I was embarrassed to confess my unresolved memories to Millette. Especially when he told me he saw Poulin’s lifeless body in the hallway. No one should ever see such gore and I told Millette I was sorry he had. A few months after we began talking, I sensed Millette’s lingering pain ease. He connected with some classmates from his religion class, which led to beer meet-ups with old friends. They talked about the shooting, but also about the zany antics that go with Grade 13. This was the first time I could hear a lightness in his voice, reliving some of the joy of being a teenager. And I, too, after all this began to feel less isolated about the shooting. That one day aside, I cherish my time at Pius. For years I had a lot of anger about the shooting's aftermath — but blame now is pointless. Our teachers did what they thought was right in 1975 — clean up classroom 71, don’t bring up the shooting and move on. Earlier this year I tried connecting with those from that class that day. Most never returned my messages. Some told me they had no lingering effects. To this day, one injured student carries dozes of pellets in his body. Yet he prevailed, living what I see as a good, unhaunted life. Others carry deep trauma that still seeps with hurt. One told me of a mental breakdown. Others told me they always scanned university classrooms, looking for alternate exits. I feel such sadness for them and wonder if their pain will ever fade. One frequently visits Mark Hough’s grave. A legacy in all forms. To this day there is no plaque or quiet memorial to mark that dark day — but it’s not too late to rectify that. Today, I have discovered that saying unspoken things out loud is not just acknowledging a tragedy but maybe expelling the worst parts. We each harboured a quiet misery for 50 years, for a lifetime — only to discover we were never actually alone. Canada's Suicide Crisis Helpline: Call or text 988.Kids Help Phone: 1-800-668-6868. Text 686868. Live chat counselling on the website.Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention: Find a 24-hour crisis centre.This guide from the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health outlines how to talk about suicide with someone you're worried about. If you're worried someone you know may be at risk of suicide, you should talk to them about it, says the Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention. Here are some warning signs: Suicidal thoughts.Substance use.Purposelessness.Anxiety.Feeling trapped.Hopelessness and helplessness.Withdrawal.Anger.Recklessness.Mood changes. ottawafirstperson@cbc.ca