Copyright abc

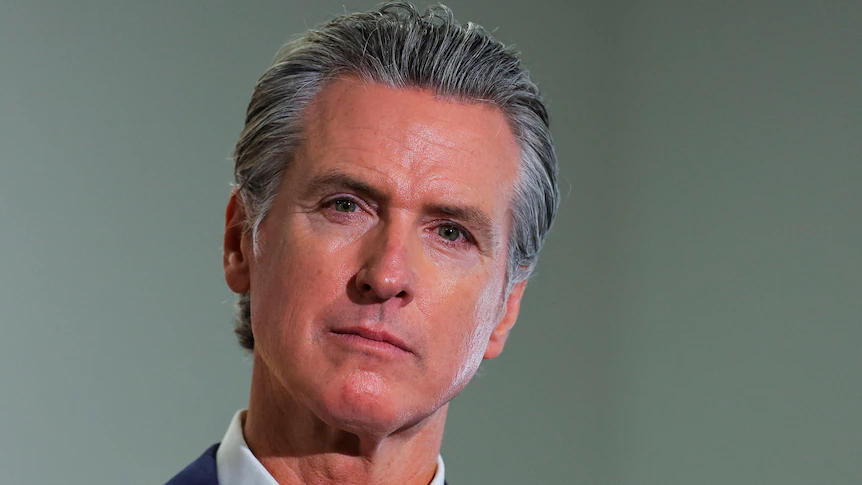

"We're fighting fire with fire," California Governor Gavin Newsom said last month at an online campaign event in support of Proposition 50, also being referred to as the Election Rigging Response Act. "We're not fighting with one hand tied behind our back." Newsom's choice of metaphor feels appropriate amid a red-hot debate about the state of American democracy, as he campaigns for voters to approve a set of gerrymandered maps: maps drawn with the goal of gaining an advantage. In this case, the goal is to hand the Democrats more seats in congress. It's an audacious move to ask voters to tilt the election battleground in your favour, but recent polls indicate the proposition will most likely pass, including a CBS/YouGov poll which found 62 per cent support. And it'll pass with Democrats claiming the moral high ground, because this is a tit-for-tat move, designed to neutralise Republicans who did much the same thing in Texas earlier this year. "If Californians don't pass Prop 50 on November 4th, Donald Trump will rig the 2026 election and steal control of Congress," the Yes campaign's official website declares. A 'race to the bottom' Maps are ordinarily redrawn every 10 years after the census, but in July, Republicans launched an extraordinary mid-cycle bid to change Texas' map, notionally handing themselves up to five extra seats. It improves Republican chances of maintaining control of the House of Representatives after next year's mid-term elections. There is plainly no way to view the Republican manoeuvres in Texas as anything other than the people in power manipulating the rules of the game for the purposes of entrenching and growing their power. They're not even pretending otherwise, given that President Donald Trump told CNBC in August that "We have a really good governor, and we have good people in Texas … and we are entitled to five more seats." "It's not usual to have re-districting happen in the middle of a decade," UCLA law professor Richard Hasen says. "It does happen occasionally, but this is 100 per cent driven by Donald Trump's attempt to try to fight against what many people see as inevitable, which is Republicans losing control of the House of Representatives. "It really is a race to the bottom." The maps have passed, although they're now facing a court challenge, and the saga has triggered what feels like a widespread gerrymandering arms race. Missouri and North Carolina have also changed their districts, and Trump has pressured other Republican-run states, while Democratic governors have indicated an intent to do the same. This, by the way, is all perfectly legal. The country has always had a decentralised election system that hands significant power to set the rules of the contest to officials at the state and county level, who are typically partisan. When the Supreme Court ruled on it in 2019, it explicitly permitted states to gerrymander their congressional districts for the purposes of advantaging one side. And so, an electoral system that implicitly permits shenanigans is now coming up against a highly polarised political culture, and politicians with an increasing penchant for shenanigans. It makes political sense for Democrats, confronted with what they see as a real threat that they'd be shut out of power, and an undermining of their democracy, to respond in this way. Not fighting fire with fire would seem to be tantamount to giving up. But fires can easily jump containment lines. If everyone is brandishing flames, it seems inevitable that someone will get burnt. "At the very least, it undermines people's confidence that the rules are fair," Hasen says. "Everybody's being accused of rigging the election or cheating … I mean, the language is very heated." What damage will be done to American democracy if an uncontrolled inferno breaks out? Democrats are claiming the moral high ground Grant Reeher, a political science professor at Syracuse University, says an increased pace of partisan gerrymandering is not good for democracy. "If this is explicitly undemocratic, then is leaning into that somehow okay, because the other side is doing it?" Reeher says. "That doesn't make the Republicans right in what they did, but it diminishes, I think, the high ground for the Democrats." As the congressional map has become increasingly gerrymandered, the number of competitive seats in congress has shrunk. It has contributed to politicians being entrenched in their positions and less accountable to voters. This extraordinary mid-decade round of gerrymandering raises the prospect of it going into hyper-drive. "The big question is, where does it stop? If we're going to do it for 2026, are we going to do it again for 2028 and for 2030?" Reeher says. "If the American way of doing this is a problem, then you're just putting it on steroids by doing it over and over again throughout a decade rather than just going through the jolt every 10 years." The gerrymandering catch-22 Polling consistently shows that gerrymandering is unpopular among voters. Even many politicians will tell you they'd prefer it wasn't a feature of their political system. The trouble is, the people who can change it are precisely the same people who benefit from the system as it stands: members of congress. And no one will unilaterally lay down arms, because why would they? "Congress has the power to make or alter any rules related to the running of congressional elections," Hasen says. "Congress could say, 'You can't engage in partisan gerrymandering', and they could define it. "The problem is that there's no political will to do it, and so I'm afraid the race to the bottom is not going to be solved until there's some change in who controls the government." Something that is made ever more unlikely, the more that partisan gerrymandering occurs. A hard cycle to break Reeher says that we might see this wave of gerrymandering die down if one side of politics manages to pull off a big win. As long as the congress is controlled on a razor-tight margin, the temptation is there to hunt for whatever advantage you can find in the congressional maps. If one side were to win with a more significant margin, you wouldn't be able to gerrymander your way to victory. But this is far from the only thing undermine Americans' faith in elections. "The biggest concern … is that the American public will no longer have a baseline level of trust in the voting system," Reeher says. "That would be existential." Trump has talked of trying to ban postal voting and in-person voting machines and has shown little regard for legal barriers and court decisions he disagrees with. "I think in the short term, things are looking very bad," Hasen says. "The question is, is America going to remain a democracy?" "I'm hoping that as we come out of the next five to 10 years that there actually would be a movement towards improving democracy in the United States. "But I think we're really at a pivot point. And we'll see how things go in the 2026 and 2028 elections to see if American democracy can survive this current moment."