Copyright Slate

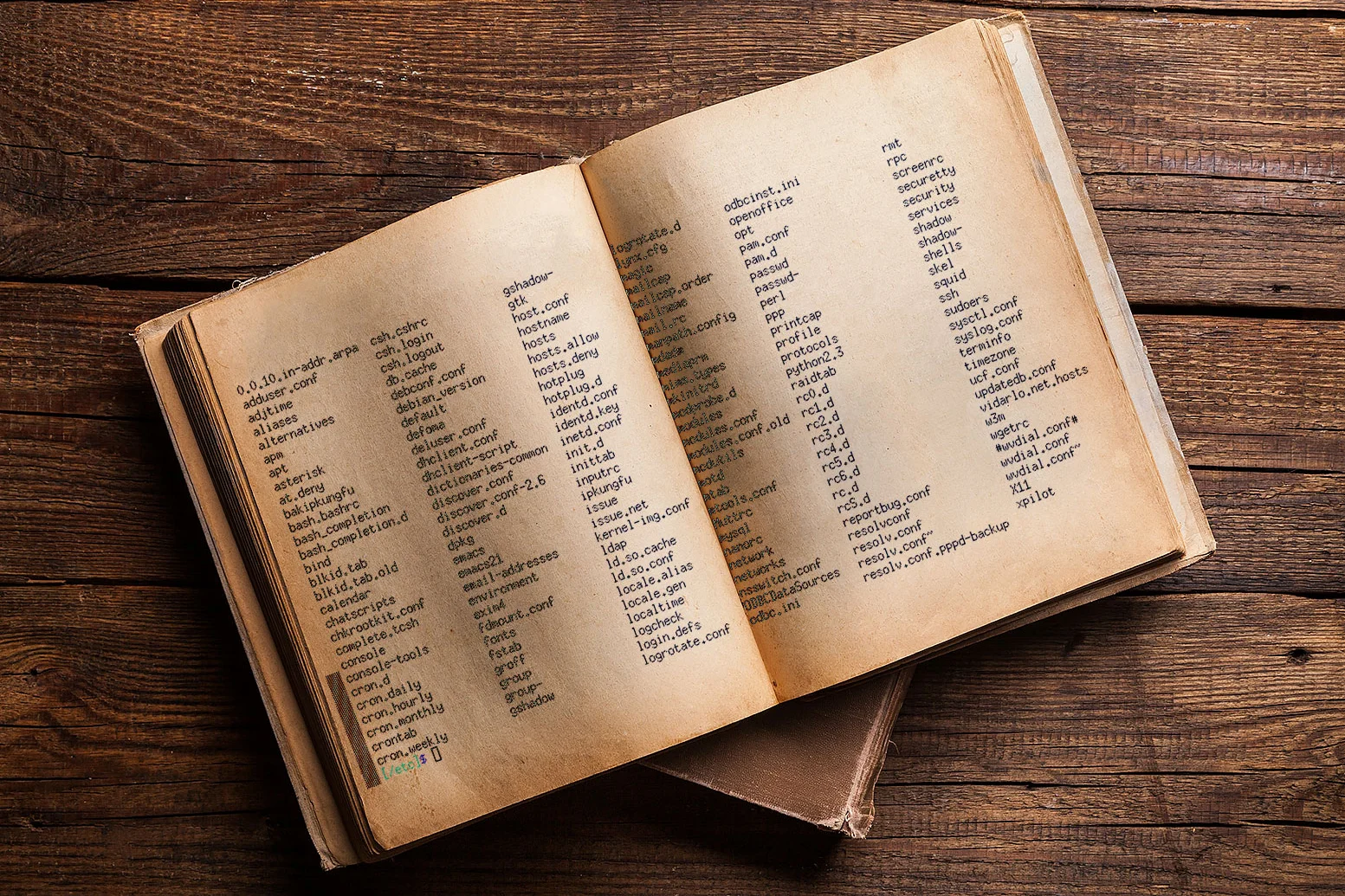

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily. Even if you’ve never heard of Arcadia Publishing, you’ve undoubtedly come upon their books at some point—displayed in a gift shop kiosk, stocked in an airport bookstore or neighborhood library, or even at a CVS. The branding remains distinct across its nearly 17,000-title catalog: a small hardbound or paperback book that catches your eye via large sepia images and titles like Theatres of San Francisco and Central Kentucky Postcards, inscribed in the style of an old-school street sign. No matter where you go across America—the mountains of Wyoming, a small town in Indiana, or the swamps of Florida—you’ll seemingly find a book from Arcadia about the local history. “They connect with a lot of historians, or locals who have an interest in history, to publish these picture-heavy books,” Alex Brown, a Bay Area librarian and two-time author for the Arcadia imprint History Press, told me. “A lot of Arcadia authors are just regular people: older volunteers at historical societies, or retirees who really like local history.” Brown is a California native who studied Black communities in the North Bay for their master’s degree and got to apply their intimate knowledge to write 2019’s Hidden History of Napa Valley and 2020’s Lost Restaurants of Napa Valley and Their Histories, after a representative from History Press connected with them a few years prior. “My first book focused on the people with marginalized identities—people of color, immigrants, women—who’d lived there.” Brown didn’t hear much from the company after 2020. Then, on July 11, they got an email from out of nowhere: Arcadia Publishing had been “presented with an opportunity to provide content to a major technology company involved in AI development,” according to the message. Brown was given a deadline of one week to decide whether the books they’d written for the imprint could be used “for AI training purposes.” It was an odd request, not only for the hasty deadline, but for the lack of details. The “major technology company” went totally unnamed; Arcadia only offered the guarantee that the artificial intelligence firm was a “trusted partner” as determined by a round of “serious deliberation.” The publishing house also made clear that its contracts allowed the company to farm its books out to A.I. models without the writers’ permission, but added that it “values its relationships with its authors” and wanted to grant them “the opportunity to opt out in this specific instance.” The particular instance, between Brown’s two titles, also wasn’t clarified. The email added that inaction would be considered endorsement; if Brown didn’t respond, they would simply receive a $340 check by the end of the year. But if they wanted “to opt out of the use and receive no payment,” they would have to visit a hyperlinked page and follow the instructions. Brown already had a sour A.I. experience: Their two books with History Press had also been included within Library Genesis, the mass set of pirated texts that companies like Anthropic and Meta had illicitly downloaded to train their large language models without requisite author compensation. So Brown was not inclined to give up their work to yet another artificial intelligence enterprise, especially one that didn’t reveal itself up front. After contacting an Arcadia representative and speaking with their prior editor, Brown found out that their second book with History Press was “not included in this specific data sale.” So they opted the first book out, turning down the $340 offer that would have made for the only check Brown had ever received from Arcadia. “Their contracts, at least at the time, were not negotiable. You basically sign it or you don’t,” Brown said. “It’s a very different structure from the Big Five publishers. You don’t get an advance or anything. You just get the royalties.” But those royalties only come in if the books in question get decent sales, something that’s harder for a locally focused outfit like History Press and a broadly niche-interest publisher like Arcadia. In a 2022 blog post, the New Jersey–based nonprofit Mr. Local History claimed that Arcadia offers “one of the lowest royalties paid to authors in the publishing world,” pointing out that “authors get $1 or less for each book sold” and are compensated only twice a year, “whereas many other publishers pay monthly or quarterly.” Such hyperlocal histories are a crucial resource, a way for particular communities to preserve and chronicle their cultures, as well as a means for marketing their regions to tourists and chance visitors. But their audiences are consequentially limited, so Arcadia does not usually approach its authors with hundreds of dollars on offer. In its email to Brown, the publishing house even pointed out that these opportunities for author compensation “could be very limited in the future,” pointing to summertime court verdicts that recognized the A.I. training process as fair use—even with copyright material. Arcadia was offering its authors a favor, while making clear it didn’t have to, and pointing out that this could be their only chance. Arcadia is hardly the only book publisher to ink such opaque contracts with the A.I. overlords, despite the spirited objections and lawsuits brought by various authors. University and scholarly presses—which have been confronting the fallout from the Trump administration’s mass grant cancellations, higher printing and shipping costs from tariffs, and industry headwinds—are providing the model. Taylor & Francis, an academic publisher based in the United Kingdom, signed a $10 million deal with Microsoft last year to share a portion of its catalog for A.I. training, in exchange for annual payments from the tech giant through 2027. Authors were reportedly given no notice and their royalties were measly in turn; Bloomberg quoted one anonymous Taylor & Francis author who claimed to earn only $97 for ceding their book to the training maw. (A T&F spokesman told Bloomberg that the payments were “in accordance with the licensing terms and royalty statement periods in their contracts,” while parent company Informa declared in a press release that “the agreement protects intellectual property rights.”) Wiley, an over-200-year-old academic publishing house, has already struck multiple A.I. deals for licensing and product integration, offering up its works to inform the output of Perplexity’s LLM and Amazon Web Services’ chatbot. For the publishers, the arrangements were lucrative. For the authors, the payouts were much less so. In July, Johns Hopkins University Press gave the authors of its 3,000-title catalog an Aug. 31 deadline to opt out of having their works become A.I. training fodder in a new tech partnership. If they opted in, they would receive a little under $100 per work. Like Arcadia, Hopkins Press did not disclose the A.I. company involved or the money it was hoping to earn. It did press the urgency of signing now while writers still had some agency, and reminded them who here really has the power. “In your contract, you provide us with the rights to go ahead with this kind of licensing,” Barbara Kline Pope, executive director of Hopkins Press, wrote to her writers. “However, we would like you to have the ability to opt out if you so choose.” The press was not suffering businesswise, she clarified, but it was “exploring how our financial model may need to evolve.” One author who went for the opt-out contract addendum with Johns Hopkins Press shared the resultant language with Inside Higher Ed; it warned that “sales and reach” of their work might suffer due to the A.I. opt-out. Beyond academia, HarperCollins became the first Big Five commercial publisher to seal an A.I. deal in late 2024 with an unnamed company—allegedly Microsoft, according to anonymous sources. Writers who opt in would earn $2,500 per book for the trouble, which wouldn’t be deducted from their typical royalties, and HarperCollins itself would also pocket another $2,500 per book. (Microsoft has not commented publicly, but HarperCollins has stated that the deal will “allow limited use of select nonfiction backlist titles for training AI models to improve model quality and performance.”) London-based Bloomsbury Publishing announced in August that it was “exploring” licensing agreements for its Academic and Professional arm, reaching out to those writers and offering just 20 percent of the money the publisher receives from the A.I. licensing deal. (The Society of Authors condemned these terms as “not fair and equitable.”) One author who’d contributed a volume to Bloomsbury’s popular 33 1/3 album-tribute series shared some of the company’s emails with me on condition of anonymity. Again, no specific partners or terms were mentioned, and the opt-out process required many steps, including an explicitly written reason for choosing not to participate. (This particular author’s simple, blunt response read, “I’m not interested in licensing my book to Generative AI companies.”) Recently, Bloomsbury’s chief publisher celebrated a concrete A.I. deal for a part of its Academic and Professional catalog—details still TBA—that apparently drove a revenue increase of 20 percent for that division over the first half of the year. As a publicly traded firm, its stock rose when the chief endorsed the possibility of even more A.I. deals on the table. The legal and regulatory landscape has provided little clarity. If anything, the courts have inadvertently revealed more on how authors have historically been exploited. In June, a federal court ruled that the prominent A.I. startup Anthropic had not committed any misdeeds by using copyright works from nonfiction and fiction writers like Andrea Bartz to train its Claude model—but it had violated intellectual property rights by pirating many of those books for training purposes, via unlawful book databases like Library Genesis and Pirate Library Mirror. To halt further litigation around said piracy, the $183 billion Anthropic agreed to pay $1.5 billion to the affected authors and publishers, making for the largest copyright settlement in history—amounting to about $3,000 per pirated work. Meanwhile, Microsoft and its partner OpenAI are facing so many copyright lawsuits from authors that the cases have been consolidated into a single instance of multidistrict class-action litigation. The argument of training as copyright infringement has managed to advance there as of Monday, thanks to output from ChatGPT that appeared to be mighty similar to George R.R. Martin’s fantasy works. In the face of a federal administration that seeks to nix all copyright protections against the A.I. sector, legal recourse remains the only potential remedy for authors. This power imbalance creates a cynical opportunity for the A.I. companies: pay the typically underpaid writers for books they were already stealing or planned to steal. A way of laundering legitimacy and skirting costly courtroom battles for pennies on the dollar. The typical Arcadia volume is chock-full of vintage photographs and tends to be less text-focused; History Press, as with the other imprints Arcadia has scooped up over time, allows authors to actually write more. The covers and branding look a touch different, but the subject matter, and the focus, is distinctly Arcadia. “You have to have a certain number of photos, a nice range of topics, and a bibliography, though they don’t care if that’s in the book or on a website somewhere,” Brown explained. Other than those conditions, Brown was free to frame the project to their liking: “I did not think that I would be able to get one of the Big Five publishers or an academic press to publish a book on marginalized history in Napa County that had nothing to do with wine. History Press was willing to do it.” It does appear that the text-heavier History Press was the focus of Arcadia’s A.I. deal. When Brown posted a Bluesky thread in July about the A.I. email, they’d hoped to hear from other Arcadia writers who’d received similar messages, but the ones who did reply and speak with Brown had no awareness of the A.I. deal, or whether their current or future works would be involved. Only one other writer, baseball historian and Kane County Cougars author David Malamut, publicly shared his Arcadia A.I. email on the social network, with its offer of $205. (Malamut did not respond to my interview requests.) Anne Trubek, the founder and head of Arcadia imprint Belt Publishing, confirmed to me that the Cleveland-based press “is not involved.” She has encouraged other authors, via her newsletter, to “get your AI money.” Stephanie Hoover, an artist and researcher who’s published three books with History Press, also put out a public ask about the deal on LinkedIn to no avail, even though she’s long been connected with many Arcadia writers. “I pitched my first book, The Killing of John Sharpless, to History Press in 2012, before Arcadia purchased it,” Hoover told me. “They accepted it so fast that I almost thought that they were pulling my leg.” The issues inherent to a quick deal with a niche business were apparent upfront. “They offered no advance. The clause that I really should have taken out was the right of first refusal, which boxed me in,” she explained. Hoover’s last book with History Press, The Kelayres Massacre, was put out just a few months after Arcadia acquired the publisher. So Hoover didn’t have much direct experience with Arcadia until the A.I. email—by which time she’d worked with bigger publishers: “I actually got an advance, and I actually do get some royalties.” The smaller earnings from History Press/Arcadia were what soured Hoover and led her to notify them, in 2016, that she would no longer run book ideas by them: “Most of the time, I’d get these royalty statements like, Nope, nothing this time, nothing this time,” she said. That pushed her to take the A.I. deal for all three of her titles, equating to $1,020, or $340 per book—the same value as Alex Brown’s offer, but more than the compensation offered to David Malamut. “I looked at my husband and said, ‘This will literally be more money than I’ve made on all three books,’ ” Hoover said. “I’m not a fan of A.I. I think it’s a threat to so many industries. But the bottom line was, A.I. is going to cannibalize my books at some point anyway, whether I want it to or not. At least this way I make something.” Still, it’s not as though she considers that price tag to be sufficient. “It took me about six months to research each of the books, and anywhere from three to four months to write them. This is a big chunk of your life, and I did it three times,” she added. “It’s frustrating when you invest that sort of time and labor to make next to nothing. It’s heartbreaking.” Michael Burgess, former director of the New York State Office for the Aging under Gov. Eliot Spitzer, had a unique introduction to Arcadia. His self-published local history, 2021’s Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt in New York, was republished by History Press in 2023 and retitled with a focus on the state capital, Albany. After Burgess got the A.I. email, which also offered the $340 royalty, he wrote an optimistic PSA on LinkedIn touting the “unexpected small financial benefit from artificial intelligence,” noting that Arcadia’s offer was “worth the small royalties I get for about 200 book sales.” “I get 7 percent of the sale of a $25 book,” Burgess told me. “I spent all this time writing it. You never get a lot of money.” The time he put into the book required research that, he believes, A.I. cannot do. “I go to the New York State Library, and I’m able to look on microfilm at the papers of Franklin Roosevelt as governor,” Burgess told me. “The A.I. is not going to go and get microfilm, I can tell you that.” He likewise mentioned a 1955 Eleanor Roosevelt radio interview he uncovered—which he could access and contextualize because his father was the correspondent. But for Burgess, it even goes beyond research. “I used ChatGPT and put something in about Eleanor Roosevelt, and it said, Eleanor and her husband Theodore Roosevelt,” he said. “I’m resigned to the fact they’re going to do this. So I’m glad I can help to give facts about this part of the story, rather than them getting it wrong about Eleanor Roosevelt.” When I reached out to Arcadia for comment, the publisher had little info to provide in terms of the partnership and its exact terms, but it did reiterate its commitment to the writers. “Any Arcadia licensing arrangements in this area will reflect our position: Authors will have a choice, and all participating authors will be compensated,” Katie Parry, a publicist and associate publisher at Arcadia, wrote in an email. “We’ll pursue opportunities that align with our position.” A lot is still unclear, but a few things are apparent: A.I. companies are aggressively reaching out to book publishers to strike deals that will allow them to sidestep the litigation that led to the Anthropic settlement and avoid the heftier payouts. Whichever unnamed firm approached Arcadia, it took a particular interest in the wordier History Press, indicating that generative text remains the lodestar. And if the Theodore/Franklin Roosevelt mix-up is representative of other chatbot hallucinations, that perhaps indicates the need not just for these bots to brush up on history and text, but to ramp up the representation of local history in the mix in order to make the LLMs more universal. If that’s the goal, at least Alex Brown’s work will not be involved: On Oct. 7, they signed newly offered addenda to their Arcadia contracts that opts them out of A.I. training offers indefinitely. Yet Arcadia as a whole, much like its fellow publishers, remains open to A.I. business. At least, while they’re still able to get anything out of the trade.