Copyright newstatesman

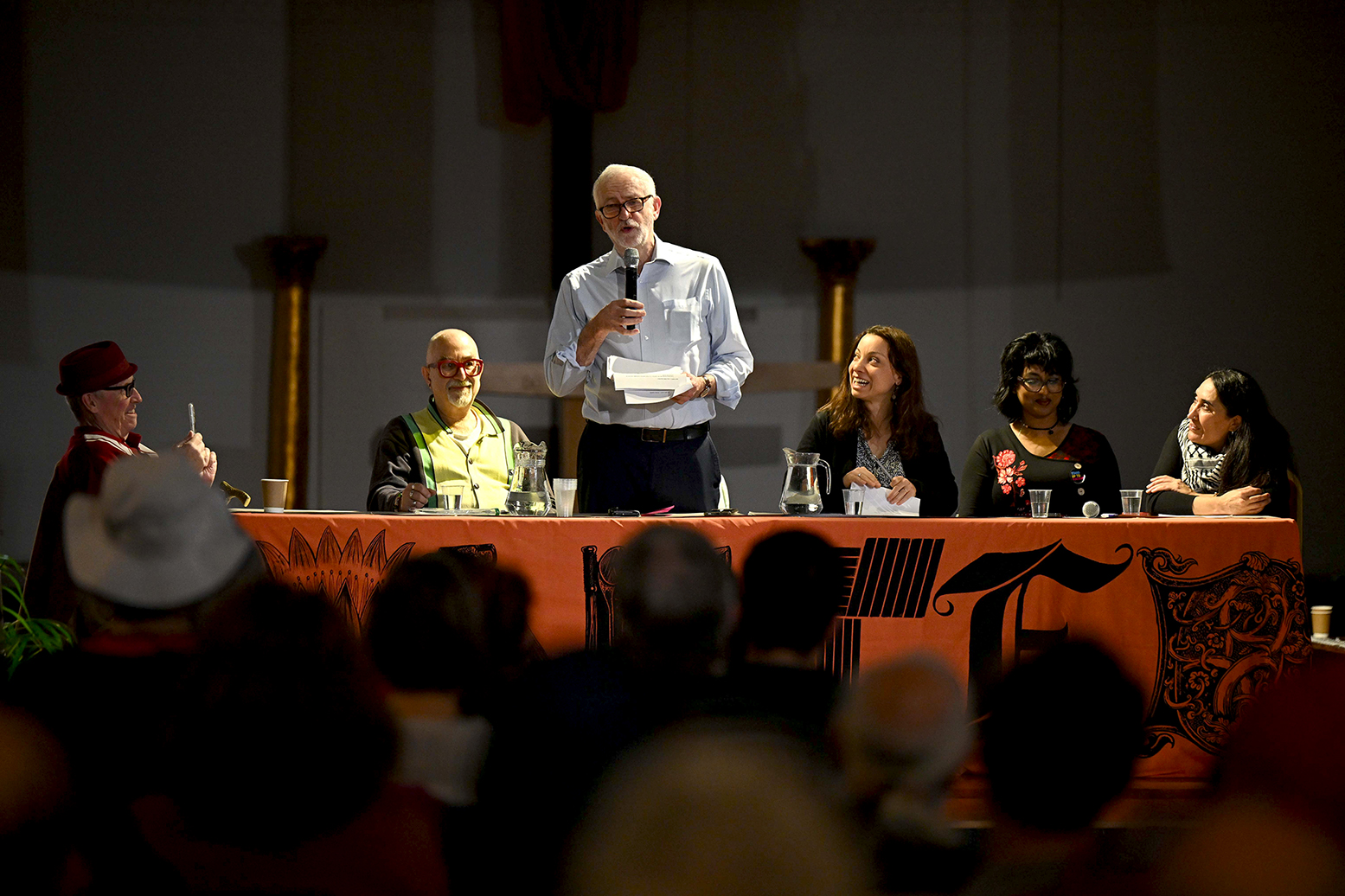

There are moments in politics when the stage changes so violently that the actors keep declaiming their lines for a scene that no longer exists. So it is in Britain. After crashing to an historically dire 11 per cent of the vote in Caerphilly, Labour was swift to get back on message, talking about… digital ID. As the government sinks to an average polling of 18 per cent, the Chancellor continues, after a miserable year of policy debacles and screeching U-turns, to rehearse the old lines about fiscal responsibility. Labour is in Pasokification territory, and either has no idea what to do about it or complacently assumes angry voters will back Labour to keep Farage out. That could work in principle if Labour were the main alternative to Reform by 2029, a situation far from assured. For, in the last two months, two major left alternatives to Labour have appeared. First, the Greens under Zack Polanski’s leadership have more than doubled their membership and are now polling in the mid-teens, sometimes level with Labour. Second, a new party – working title Your Party – is being founded with parliamentary representation and a starting total of roughly 50,000 members. This is well short of the 800,000 people who expressed interest by signing up to the mailing list, thanks to a series of tawdry scandals – but it’s still bigger than any socialist party in the UK since the 1940s. What’s surprising is how late this comes. The Greens, of course, have been around in one form or another since the Seventies, but their political stripes shift with circumstances. But unlike on the continent, the UK hasn’t had a major socialist party since the Communist Party of Great Britain. Cast your mind back to the latter half of the 2000s and look across the English Channel. In France and Germany, new radical left parties were being formed: the Parti de Gauche (forerunner of La France Insoumise) and Die Linke. Both hoped to benefit from dissatisfaction over the rightward drift of social democracy. In Portugal and Spain, coalitions like the Bloco de Esquerda and Izquierda Unida were taking chunks out of the centre-left vote. In the Netherlands, the old Socialistische Partij was suddenly polling in the double digits. Similar stirrings were visible in the Scandinavian countries. No equivalent in Britain. Particularly striking was the role of defectors from centre-left parties. In France, the Parti de Gauche was co-founded by former Socialist politician Jean-Luc Mélenchon. In Germany, Die Linke was launched by former SPD finance minister Oskar Lafontaine. These were splits from a social-democratic tradition that had been slowly involuting since the 1990s, as it embraced the bastardised Thatcherism known as “social liberalism”. Wasn’t Respect, led by former Labour MP George Galloway, the British answer to that need? Hardly. Galloway did not leave Labour voluntarily: he was booted out for encouraging Arabs to fight the troops. And he did not carry a chunk of Labour MPs, activists or voters with him, which is partly why the party imploded. No matter how dissatisfied voters were over Iraq and the Private Finance Initiative, no matter how angry the Labour left was, a split was never on the agenda. Whether this reflects defeatism, tribalism, or simple electoral calculation in a country with a first-past-the-post system, one thing can be said for it. Had Labour split in the 2000s, the party would never have had its first ever socialist leadership under Jeremy Corbyn. Granted, that experience was not entirely delightful for the left. Leading the Labour Party meant inheriting all its accumulated weaknesses, including the rot among working-class voters already flagged up under Miliband – a rot that had been largely ignored under Blair, because it was concentrated in seats with initially mountainous majorities. In fact, leading Labour meant inheriting a party in chronic decline. Labourism, as a social and civic movement with trade unions as its spine, had been collapsing since the mid-Eighties. The party’s managerial regime since Blair had seen a takeover by managers and electoral professionals with little sympathy for “old Labour”. The parliamentary party was increasingly absorbed into the Westminster machine, aloof from the electorate and certainly not accustomed to being seriously inconvenienced by the members. Hence the entitled hostility of the party establishment that encircled Corbyn’s leadership from day one. Nonetheless, until it spectacularly imploded over Brexit dithering and the failure to effectively combat anti-Semitism smears, the Corbyn leadership briefly interrupted and reversed some of the decay. The huge swing to Labour in 2017, achieved against considerable resistance from Labour officials, dispelled the myth that elections are won or lost in the centre-right or in the editorial offices of the Sun. Above all, the fragile optimism of the period mobilised and radicalised large numbers of people who – however crushed by electoral defeat in 2019 – didn’t really change what they wanted. Rather, once Keir Starmer took the reins and unleashed the hatchet men of the Labour right, they had no longer had a plausible organisational vehicle for those hopes. It has been a long wait for the left. Surprisingly long since discussions of a new party, as Ben Sellers writes, already surfaced in 2020. While some heartbroken radicals cried into their beer or briefly feigned enthusiasm for Starmer’s “soft left” ruse, talk of the need for a new organisation was already circulating among activists in Corbyn’s Peace and Justice Project. Unfortunately, it seems it wasn’t seriously considered until 2024, despite the Starmer project’s repeated crises and pre-election convulsions and mass councillor resignations over Gaza. When a new organisation was seriously broached it was only because Corbyn, having already had the whip removed, was effectively forced out, barred from standing as a Labour candidate and compelled to stand as an independent. This delay cost the left. The 2024 general election was a miserable plebiscite on managerial failure. Labour cashed in on the advanced state of Tory decay to win a loveless landslide. But the cracks were already evident. Corbyn handily held his seat, four independents won in the quondam heartlands of Leicester, Blackburn, Birmingham and Dewsbury, and the Greens added three seats to their total, raising their nationwide vote share from 2.6 per cent to 6.4 per cent. In Wes Streeting’s Ilford constituency, a hitherto unknown local candidate, Leanne Mohammed, almost unseated him. In Keir Starmer’s constituency, the one-time anti-apartheid activist Andrew Feinstein took almost a fifth of the vote. Had the outline and nucleus of a left party been agreed before then, those candidates would have had finance and campaigning support, and a known brand to run under. And perhaps, rather than politically heteroclite independents, a few socialists might have been elected. Then, too, one might imagine municipal footholds, key wards taken, mayoral campaigns fought. By September 2024, a new organisation was launched to campaign for a new party – Collective, its directors Pamela Fitzpatrick of the Peace and Justice Project, and Corbyn’s former chief of staff Karie Murphy. Corbyn, despite addressing the launch, was said to be reticent. In part, the issue seems to have been that there was no agreement as to what type of organisation was needed. Some, like Murphy, wanted a national party, while others like Jamie Driscoll preferred a federation of local efforts. It wasn’t until the spring of 2025, amid governing chaos and radicalisation to the right, that the comrades got their act together and agreed to launch some sort of organisation. An informal “organising committee” was launched, incorporating figures beyond the Corbyn retinue like Salma Yaqoob, Andrew Feinstein, and later Driscoll. A company, the Memorandum of Understanding Ltd (MOU) was set up to handle money and data, with the aim of organising support for candidates in the next year’s elections. Enter Zarah Sultana, a talented MP and public speaker, elected to represent Coventry South in 2019. Sultana was among the seven Labour MPs who had the whip removed for voting to abolish the two-child benefit cap in July 2024. This move was typical of Starmer’s authoritarianism and hubris, because it was exactly the sort of thing that might provoke the kind of split that hadn’t happened in the 2000s. Sultana was ready to defect to a new party if it was declared. Many in the organising committee appear to have seen her as a potential leader, and also a counterweight to the bureaucratic heft of Murphy. On 3 July 2025, the committee held a vote on declaring a new party with Corbyn and Sultana co-leading the founding process. The majority voted in favour. Sultana then swiftly announced this on social media, yielding a pop of enthusiasm from long impatient activists. But team Corbyn felt they had been sandbagged in the vote, in which they had abstained, and he hadn’t agreed to anything yet. They might have handled this behind the scenes and orchestrated a more cautious joint statement. Instead, they briefed that Corbyn was “furious and bewildered” by Sultana’s precipitous announcement. Then the gory details were leaked to the Times, a move so recklessly self-harming that many on the left initially assumed the journalist had been played. To the contrary, he had the receipts, including screengrabs of Yaqoob and Feinstein being booted off the organising committee group chat by Murphy. In the past, you couldn’t have tortured this sort of information out of any serious left-wing organiser. Yet the glee that Sultana’s announcement elicited exposed frustration with the delay and lack of urgency around the project. And after some equivocal statements from Corbyn favouring a “grouping” or a “united voice”, a public truce descended. The public was asked to express interest in the new party by signing up to a mailing list. Within weeks, the number of signatories totalled hundreds of thousands. At a Peace and Justice Project conference, Corbyn announced that 800,000 people had signed up. Initial polling indicated that in principle a party led by Corbyn and Sultana could get up to a fifth of the vote. A party that didn’t even exist yet. All was not well. Behind the public rows between Adnan Hussain and Sultana was an internal argument over whether MPs should be leading this founding process – as they were since the “organising committee” was wrapped up. That, coupled with Sultana’s argument that she was being frozen out of decision-making, led to her disastrous launch of a membership portal on 18 September without authorisation from the other MPs. The subsequent cycle of mutual escalation, threats of legal action and bitter language showed, as Andrew Murray wrote, scant evidence of “a sense of responsibility to the wider movement”. Indeed, despite subsequent shows of unity, the bunker mentality that leads to factional battles exploding into public hasn’t receded. Members of the new party are still treated to lurid scandal, as when the directors of MOU Operations Ltd were publicly threatened with legal action for supposedly holding on to £800,000 of donations. Or when, after Sultana took control of MOU, allowing the directors to resign in bitterness – and just a day after the membership figures were announced – the press was briefed that she was holding onto the cash for political leverage. Whatever the truth of all this, it probably reflects poorly on all involved, so the urge to leak to a gossip-gluttonous press is bizarre. In a way, the story of Your Party is of a political leadership belatedly recognising the urgent needs of a unique historical moment – a moment of elite decay, Westminster collapse, rampant racism and authoritarianism in both government and media, but also of potentially irreversible realignment if the left gets its act together – and struggling to meet those expectations. If the party didn’t answer some historical necessity, the combined chaos at the top and competition from a gifted Zack Polanski would have finished it. That all is not lost is, in its own way, a further indictment of those who have wasted so much potential already. This is an open goal. People, potentially hundreds of thousands, with spare time, money and energy to contribute, are ready to join anything with a realistic chance of not fading into obscurity. To fumble this now would be unforgiveable. [Further reading: Is Your Party having a leadership election?]