By Michael Tanenbaum

Copyright phillyvoice

One night in 1997, after an Extreme Championship Wrestling show in South Philly at what’s now known as the 2300 Arena, a young Rob Van Dam was sitting at the bar of the old Holiday Inn at the Sports Complex, and he felt a rumble in his stomach.

Van Dam, an acrobatic rising star known as the “Whole F’n Show,” got an offer from an ECW fan sitting next to him to ride over to Geno’s for a cheesesteak. None of the other wrestlers wanted to leave the hotel. Van Dam took the invitation and buckled up for a quintessential Philly experience he’s never forgotten.

MORE: As Dock Street turns 40, here’s how it grew from a countercultural idea into the oldest craft brewery in Philly

“I got in the car with this guy I didn’t know, and that motherf***er ran every single stop sign,” Van Dam said. “I don’t mean like he slowed down and looked. He kept the gas pedal on and treated the entire thing as if he had the right of way. He said, ‘You know what the good thing about four-way stops is? The other guys always gotta’ stop.'”

Van Dam reminisced about Philly and ECW while discussing the new documentary he produced with director Joe Clarke on the life of Terry “Sabu” Brunk, who died in May just three weeks after winning his final match in Las Vegas. Brunk was 60 years old. The documentary, which had been in the making for well over a year, presents a raw and personal look at the life of a retiring wrestler who seemed to be emotionally preparing for his death.

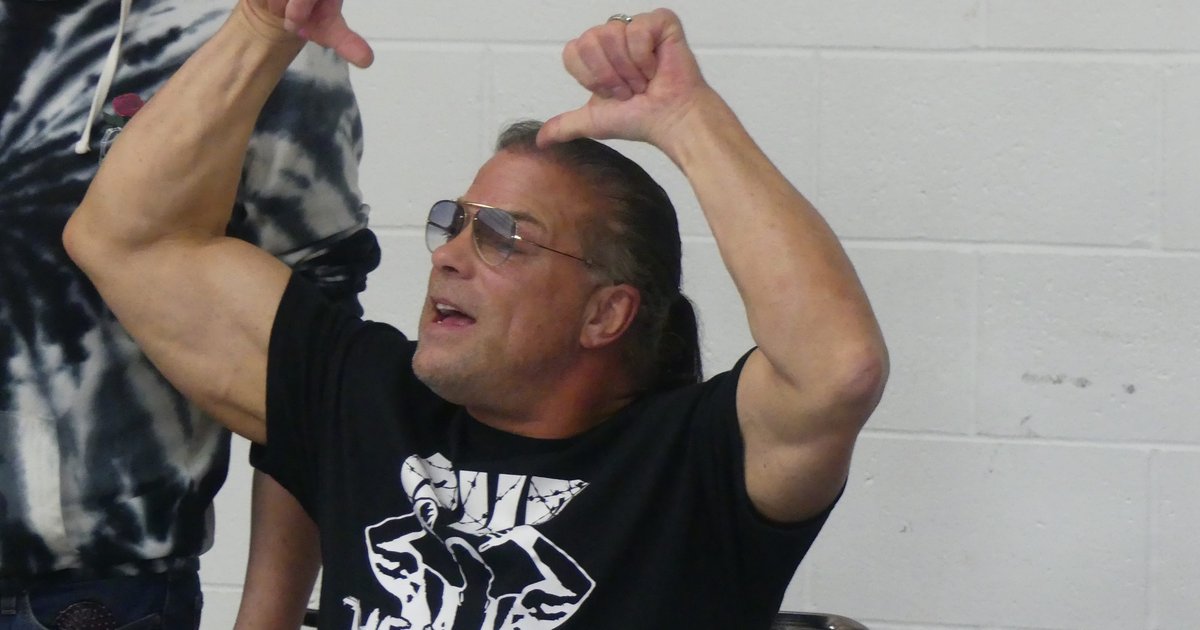

“He was one of the closest people to me, and I don’t have very many people close to me,” said Van Dam, 54. “There’s a whole lifetime of memories and inside jokes – s*** that’s just gone. I didn’t know there was that much foreshadowing in the documentary until after the fact. When I got the call, I can’t say I was that surprised because I had been expecting it for 30 years. It’s really eerie.”

Months after Brunk’s death, loved ones are still awaiting a toxicology report to pinpoint an exact cause. In the documentary, Brunk alludes to heart problems and difficulties carrying on with his life after his partner and longtime manager, Melissa Coates, died of complications from COVID-19 in 2021.

“Everyone has their own theory,” Van Dam said. “Most of it has to do with his lifestyle – that he lived himself to death Sabu-style.”

Fittingly, a memorial service for Sabu was held in June at the renovated 2300 Arena – still used as a venue for professional fights – where Van Dam spoke to a tight-knit family of mourners who had been touched by Brunk inside and outside the ring.

“He was a big part of the man that I became,” said Van Dam, who occasionally still wrestles for AEW and makes sporadic appearances at WWE events.

Van Dam joined ECW in the mid-1990’s with help from Sabu, a fellow Michigan native. They were both trained by Sabu’s uncle, a wrestling industry veteran who fought as the Sheikh, using makeshift rings set up in garages and backyards.

ECW’s arena in South Philly, near the corner of Ritner and Swanson streets, became the epicenter of hardcore wrestling in the United States in the early 1990s. While promotions like WWE and WCW were duking it out for mainstream market share in an eventual multibillion dollar industry, ECW existed as a reckless talent incubator with an underground edge.

“It was a pivotal platform for the wrestling business to go in a whole different direction, where instead of worrying about (being) politically correct and entertaining kids, it was adult entertainment,” Van Dam said. “It was unapologetic. The storylines were crazy. It was a full circus with completely different styles of wrestling, but altogether we were this family that was so grateful for what we had.”

Sabu, who donned a turban as part of his extremist persona, became an innovator of brutality in ECW. He was among the first U.S. wrestlers to popularize plowing through tables, rolling around in barbed wire and wielding various weapons in his offensive repertoire.

Van Dam remembers nights at Philly hotels filming promos for upcoming matches. ECW owner Paul Heyman would keep his wrestlers waiting all night to get paid, leaving hours for them to get drunk and high before hopping on flights to the next venue.

It was an exhilarating lifestyle for muscled young people full of ambition, Van Dam said, but Sabu was a hardcore wrestling purist and a deep believer in karma being a reward system. He struggled with the entertainment side of the business as he got older and his WWE career plateaued, landing him back on the independent circuit.

“He should have been a much bigger star,” Van Dam said.

ECW shut down in 2001 after a failed national TV deal and financial struggles led to its bankruptcy. Looking back, Van Dam thinks the writing was on the wall in 1995 when a flaming object used during a match ended up in the stands and – legend has it – burned a fan.

“The very nature of the product limited its success and its exposure because you can’t light fans on fire and not have consequences for it,” Van Dam said.