Copyright Newsweek

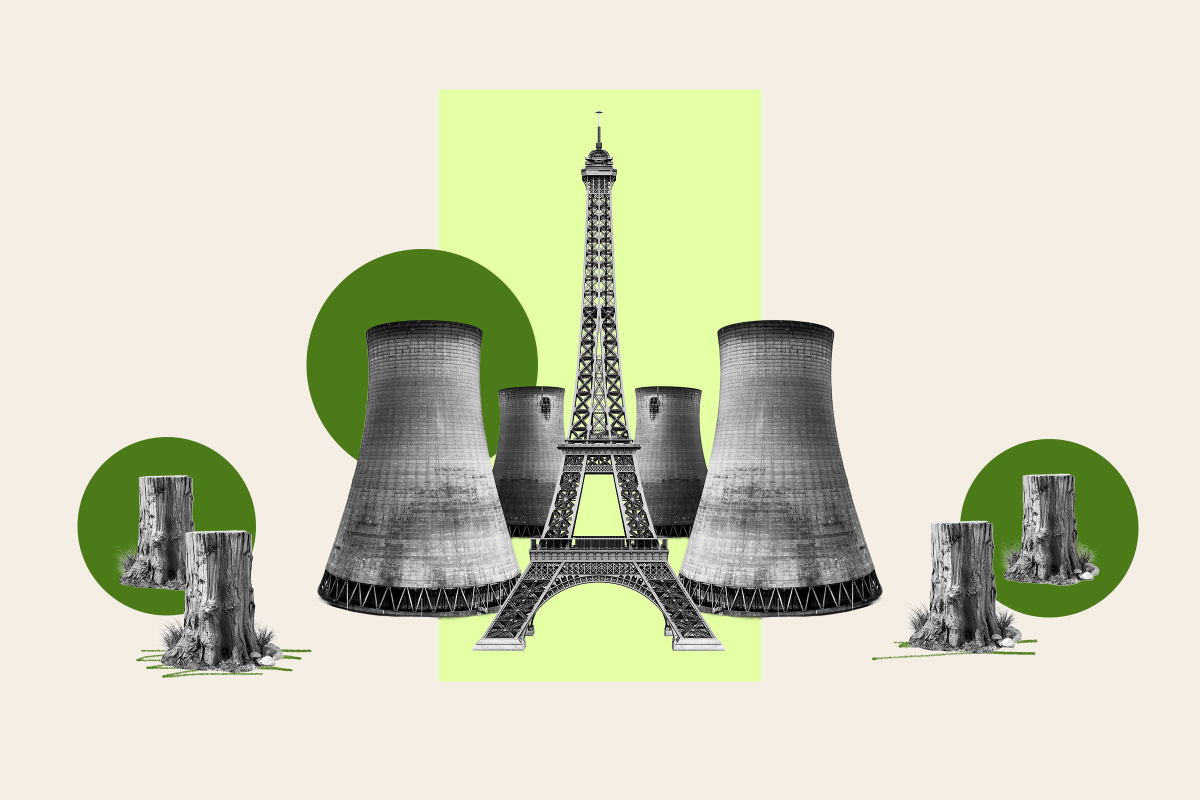

When world leaders convene in Belem, Brazil, next month for the United Nations COP30 climate talks it will mark ten years since the landmark Paris Climate Agreement to cut emissions enough to avoid the most catastrophic warming. But a pair of recent reports show that global action is not even close to meeting that goal. “None of the 45 global indicators that we track are on pace,” Kelly Levin, chief of Science, Data and Systems Change at the Bezos Earth Fund, said in a press briefing on the report The State of Climate Action 2025. Levin is co-director of Systems Change Lab, which published the report in partnership with ClimateWorks Foundation, the Climate High-Level Champions and World Resources Institute. The report assessed progress on a range of tools to address climate change, including growth of renewable energy and electric vehicles, phasing out coal and subsidies for fossil fuels, reducing deforestation and boosting carbon removal and climate financing. The researchers found that six of those indicators are improving but too slowly to meet the Paris goals, 29 are lagging, and five are moving in the wrong direction. (Another five lack sufficient data to accurately track.) “Progress is happening, but the clock is outrunning us,” Levin said. The persistence of coal-burning power, especially in fast-growing economies in Asia, remains an obstacle for climate progress. Coal is the most carbon-intensive of fossil fuels, generating more carbon dioxide per unit of energy than does the burning of oil or gas, so phasing out coal quickly is crucial to meeting the emissions thresholds climate scientists set for the Paris agreement. While coal is slowly being replaced by cheaper renewable energy alternatives, the report found that the phase-out must be 10 times faster to meet the international climate targets. That’s roughly equivalent to retiring 360 average-sized coal-fired power plants each year in addition to stopping all planned coal projects in the development pipeline. The expansion of mass transit systems should be happening five times as fast, the researchers found. Carbon removal technology needs to develop tenfold faster, and climate finance should increase by nearly $1 trillion annually. That last figure might seem like a hefty price, but the report noted that it is only about two-thirds of what world governments spend annually to finance and subsidize fossil fuels. The world’s forests play a vital role in addressing climate change as growing trees capture and store vast amounts of carbon dioxide. When forests are lost to ranching, mining and other development or due to wildfires, much of that carbon can be quickly released to the atmosphere. Reducing the rate of deforestation is therefore important not just to preserve habitat but also to prevent the prospect of runaway global warming. The researchers found that after a period of success, deforestation rates have ticked back upward in recent years. Meeting the Paris goal would require a ninefold improvement in forest protection. Another report released last week by a coalition of civil society and research organizations went further into the details of forest loss. The Forest Declaration Assessment found that world leaders are missing self-imposed goals to end deforestation by about 60 percent. The study found that in 2024, about 20 million acres (8.1 million hectares) of forest were permanently lost, an area roughly the size of South Carolina. “Every year, the gap between commitments and reality grows wider,” report lead author Erin Matson said in a press briefing. “We already know what works to stop forest loss, but countries, companies and investors are only scratching the surface.” COP30 will be the first of the annual climate negotiations to take place in the Amazon, putting a spotlight on forests and other ecosystems as nature-based solutions for climate change. Host country Brazil is planning the launch of an innovative system to finance forest protection called the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF). The TFFF goal is to take billions in public and private sector dollars to invest in financial markets, then use the returns to assist conservation and restoration in forested countries. COP30 will also mark the start of new government plans to cut emissions under the Paris Agreement. The Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) have been slowly emerging, and policy experts are watching closely to see if the ambition of the plans meets the scale of the challenge. In a briefing for journalists on Wednesday, Cassie Flynn, global director of climate change at the U.N. Development Programme, said that while several major emitting countries have yet to release their plans the ones that have been presented so far show a “huge step” in quality compared to what countries offered in the past. (In the closing days of his administration, President Joe Biden submitted the U.S. plan, however, the Trump administration is pulling the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement.) “We are on the verge of a breakthrough with what these NDCs represent,” Flynn said, adding that those commitments must then be matched with national policy and budget support if the world is to get back on track toward meeting climate goals. “Can we realize the potential of these NDCs and see them implemented to the speed and scale needed?” Flynn said many countries are seizing the economic opportunity that is now possible with climate action due to the falling cost of renewable energy sources such as wind, solar and battery energy storage. That’s a point Levin at the Bezos Earth Fund also emphasized, comparing the status of clean energy and EV markets today to what existed with the Paris Agreement was signed a decade ago. In 2015, EVs made up less than 1 percent of total passenger car sales. Today, about one in five passenger cars is electric, and in the world’s biggest car market, China, EVs are roughly half of new car sales. “The good news is that reality has outpaced many of the projections a decade ago,” Levin said. But emissions continue to rise, Arctic sea ice has hit a record low, and the past ten years have been the warmest decade on record. Clean energy is advancing but not as fast as the relentless march of climate change. “While the arc of progress has bent sharply towards possibility,” Levin said, “it must now bend faster toward the pace that science demands.”