By Olatunji Ololade,The Nation

Copyright thenationonlineng

Immigrants battle rising xenophobia as irate mobs barricade hospitals, schools

Conflict mimics apartheid era violence amid South Africa’s anti-immigrant rhetoric

Culprits must be arrested, prosecuted, says NIDCOM boss Dabiri-Erewa

Tola Shoile endures Johannesburg like a mental wound. Twelve years after he relocated to the South African capital to make ends meet, the city seems poised to end him.

“Jo’burg has taken too much from me. It cost me my business and bankrupted me. I lost everything in the xenophobic attacks of 2022,” he said, recalling how two members of his staff led an assault on his auto dealership in Cleveland, Johannesburg.

Shoile disclosed that it took him a long while to recover from the shock of the betrayal. “I was very good to them. And I gave them bonuses even when they hadn’t earned it. Yet, they led a mob to burn down my shop. They burnt about 50 cars,” he said. “They accused me of taking their jobs but how is that possible when all I did was provide them employment? Now, they have started again,” said Shoile, bemoaning the recent wave of xenophobic attacks spearheaded by the Operation Dudula movement.

Shoile’s fears are accentuated by the sad fate of fellow migrant, Ifeanyi Obi. Few months ago, Obi encountered terror in common hours. The 41-year-old had gone to the Jeppe Clinic with his wife and daughter for a post-natal check-up. While in the clinic, he stepped outside to “receive a package” from a client with whom he had previously fixed a meeting.

“On my way out, I saw a crowd assembling at the hospital entrance and I suspected that it was the Dudula gang. But I had to get the cash from my client. I discharged him immediately and

returned to get my wife,” he said.

But as he approached the clinic, Obi saw that the crowd, previously scattered and ragtag, had coalesced into an organised mob: men and women from Operation Dudula milled around the hospital chanting “Foreigners must go!”

As tensions intensified, the mob prevented Obi and a few others trying to access the clinic. To their chagrin, security personnel watched unperturbed as mothers with babies and other patients identified as foreigners were shoved back into the street.

A section of the mob surged towards him and Obi scampered to safety. From a distance, he craned his neck to see if his wife, Bridgette, would emerge with their daughter pressed safely to her chest. But she didn’t.

Read Also: Shadow govt: Pat Utomi knows fate Monday as court delivers judgment in DSS’ suit

“I went back later, after the mob dispersed, but I couldn’t find them. I dialled her number unsuccessfully and called our friends but none of them had seen her. I was so scared,” he said.

Bridgette would later reach out to him from the outskirts of Johannesburg via a terse message. “I am at my cousin’s,” she said. She subsequently called him at midnight to tell him that: “A man like you stayed back to help me.” Since then, they have been estranged from each other.

The Obis represent a fragment of a wider migrant community afflicted by South Africa’s xenophobic rage. Across Johannesburg’s inner-city tenements and the scattered townships of Gauteng, several migrant families, grapple with the consequences of xenophobia and other forms of anti-immigrant hysteria. Husbands vanish in street attacks and wives retreat to safer districts or back across the continent.

For Rotimi Adegboye, the experience has been both “good and bad.” According to the 48-year-old, who hails from the Omowumi Abisogun Royal Family of the Iru/Ilashe kingdom in Eti-Osa area of Lagos State, since he relocated to South Africa in 2006, he has met with lots of wonderful South Africans who accepted and befriended him without discrimination.

“On the other hand, I met with some South Africans that get intimidated because I am Nigerian. These ones attack you verbally, directly and indirectly, labelling you a drug mule or a scammer,” said Adegboye, adding that he has never suffered any grievous xenophobic attack.

Yet, Oyindalopo Muyiwa, 46, recalled how her Zimbabwean neighbour was hacked in broad daylight, and the night a Malawian acquaintance’s cries carried through the alley as he was burned to death by people who used to be their neighbours.

She subsequently relocated from her “toxic neighbourhood in central Joburg” to the northern part of the city, and subsequently, “a more friendly environment in Ontario, Canada.”

South Africa, according to Muyiwa, is fast becoming a graveyard for African migrants and she didn’t wish to become a random casualty of xenophobic attacks by natives who think of immigrants as criminals and social parasites stealing their jobs and medicines.

The hospital, internet as battlefield

Through it all, the Operation Dudula movement has found a new stage for its campaign of erasure: the public health system. Hospitals and clinics, once sanctuaries for healing have been turned into scenes of exclusion. Recent viral videos circulating online, show men and women storming waiting halls and commanding patients to stand if they are foreign, demanding proof of their citizenship before they are allowed access to treatment.

“If you know yourself that you are not a South African, please stand up,” one Dudula leader barked menacingly at the Roodepoort Clinic. “Don’t try us. We will check everybody.”

The viral video of a defiant Nigerian woman being chased from a South African clinic and the euphoric approval by South Africans of the treatment meted to her further accentuates the wider climate of anti-Nigerian sentiment that has long simmered in the country’s streets and now thrives in its digital commons.

Clutching her infant daughter in one arm and medical documents in the other, she dared her assailants to assault her even as she hurriedly left the hospital – without seeing the doctor – for her safety and that of her child.

But rather than show compassion for mother and child, most South Africans on the comment thread attacked her.

“Her bold attitude would have helped her in Nigeria, but no, she chose to come to SA to fight for her wrongs,” wrote @andiswatembela4942. His words setting the tone for many others who framed the woman’s presence in the hospital as an unwelcome intrusion.

@NtombiMaseko-m7d was blunt: “Let them go,” and @PenelopeNgqumaza insisted, “Go and shout in your country.”

The repeated use of “makwerekwere,” a slur for foreign nationals, underscores hostility. “Makwerekwere hasihambeni,” posted @LinaAkokwa. “Hambani makwerekwere,” echoed @sisterashericharmaine1602.

For many, Operation Dudula embodies patriotic action. “Viva Dudula and March on March,” declared @thabojosepgsekhabisa9593, while @LizaMashaba celebrated: “Viva Dudula viva.” @BulelwaMatiwana-q9k added, “Thanks, viva Dudula vivac,” and @mrscashqueenb8855 endorsed the group’s stance: “They are doing a great job… even in Nigeria there is no free clinic and hospital.”

Beyond nationality, some reduced the woman to a caricature. “They always shout. Fighting. Imagine this Nigerian oooo,” wrote @PenelopeNgqumaza. While others framed her “boldness” as arrogance. For @andiswatembela4942, her assertiveness was evidence that she didn’t belong.

The stereotype of Nigerians as combative, disorderly, and unwilling to assimilate saturates the views while the struggle over scarce resources was a recurring theme.

“There is a Nigerian who was talking on TikTok who said they have free hospitals in Nigeria lol, so my question is why they come to SA manje?” asked @triston9618.

“Why would you have multiple children in a country you are not familiar with and you weren’t born in?” questioned @NomalwandleNdlovu, who acknowledged trauma for the woman’s children but still placed blame on her choices.

The rhetoric sometimes turns chilling. “Uyazi lezizinja zama Nigeria kumele kezifundiswe isifundo,” posted @MarrySithole, adding that “These Nigerian dogs must be taught a lesson.”

Yet amid the hostility, a few commenters pushed back. “This aggression of yours bro, is not necessary,” countered @rejoicevuragu651.

“It’s painful though,” admitted @phumilushaba4892. “Chasing poor women and children is wrong,” said @PaulineVeremu.

@brewedcoffee727 struggled with ambivalence: “This feels harsh and it’s pulling on my heart strings… painful to watch. But it has to be done… there needs to be order.”

A broader reflection came from @TinasheManuel: “South Africa is isolating itself from a future that is united.”

Some redirected their frustration toward the South African government. “Ma South Africans, let’s fast move this issue yamakwerekwere, so we can proceed to fight this Cape Independence. The country is going thanks to ANC & DA,” posted @ndukhumalo7794.

The hostile commentaries illustrate how Nigerians are perceived as invaders by members of their South African host communities. The widespread support for the Operation Dudula shows how the sentiment is deeply entrenched in everyday discourse. While a handful of voices call for empathy, they are drowned out buy a swell of resentment.

On social media, as on the streets, Nigerians in South Africa face a reality where their very presence and humanity are contested and too often denied.

Offline, inside the clinical halls of Yeoville, Roodepoort, Lilian Ngoyi, and beyond, the refrain is the same: foreigners out.

Pregnant and nursing mothers, including Nigerians, are driven out of hospital waiting halls and labour wards. Consequently, some pregnant women have gone into labour and birthed their children outside barricaded hospitals, unattended by qualified medical personnel.

The Nigerian Union South Africa (NUSA) has catalogued these horrors: infants born on the cold bare floors, and mothers bleeding, unattended to, in waiting areas, as their weeping husbands are beaten up and chased away from hospital gates.

NUSA President Smart Nwobi, a human rights lawyer, described the actions as “illegal and xenophobic,” warning that Nigerians are “dying daily” due to the blockades. “They are criminals operating under the guise of community activism,” Nwobi told reporters, urging President Bola Tinubu to raise the issue at the upcoming G20 Summit in Johannesburg.

More Nigerians in South Africa are pleading for urgent diplomatic intervention as the anti-migrant vigilante group escalates its campaign of intimidation, blocking foreigners from public hospitals and forcing vulnerable women to give birth on bare floors amid a fresh surge of xenophobic threats.

Community leaders report that the group’s members have been aggressively confronting patients at facilities like the Roodepoort Clinic west of Johannesburg, demanding proof of South African citizenship before allowing entry.

In viral videos circulating online, Dudula activists are seen marching through waiting areas, ordering non-citizens from Nigeria, Zimbabwe, and other African countries to leave immediately.

“If you know yourself that you are not a South African, please stand up. Stand up right now. Don’t try us because we are going to check everybody,” one leader declared in a clip that has drawn widespread condemnation.

Operation Dudula’s gospel of expulsion

Operation Dudula, founded in Soweto in 2021 and now a registered political party, claims its “Put South Africa First” slogan addresses crime, unemployment, and strained public services caused by undocumented migrants.

Nhlanhla “Lux” Dlamini aka Nhlanhla Mohlauli, a South African activist, pilot and anti-immigrant activist, founded the movement at the age of 35.

The group’s name, meaning “to force out” in isiZulu, reflects its goal of expelling perceived illegal immigrants, whom it accuses of fueling drug trafficking and job theft.

The movement’s incumbent leader, Zandile Dabula, recently announced plans for a December 2025 school blockade campaign to bar non-South African children from enrollment, signaling further escalation amid claims that she actually hailed from Zimbabwe, and not South Africa.

Speaking to the media on Monday, Dabula clarified that she is South African. She responded to critics calling for her deportation that she was born in Soweto.

“I’m a bona fide citizen of this country. I was born and bred in Diepkloof in Soweto and not in Zimbabwe. That’s the only reason I want to put my fellow South Africans first, because I know their struggles,” adding that she is a victim of a smear campaign initiated by members of the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF).

The EFF leader, Julius Malema, had taken a swipe at Operation Dudula, calling it “a group of thugs.”

Malema said on X: “Operation Dudula is a group of thugs and must be subjected to the political killing task team. Period!”

Interestingly, his statement ignited backlash from his supporters, with some accusing him of prioritising foreigners over South Africans and threatening to punish him at the polls.

On its part, the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) has dismissed claims that it is protecting illegal foreigners due to its stance on protecting human rights for all individuals in South Africa, regardless of their nationality or immigration status.

The commission condemned Operation Dudula, among others, for blocking immigrants from receiving medical care in public clinics and hospitals.

The commission slammed Gauteng premier Panyaza Lesufi’s plans to clear out informal settlements at night, citing concerns about the danger and trauma it may cause to vulnerable groups, thus raising further concerns about the commission’s ability to prioritise South Africans.

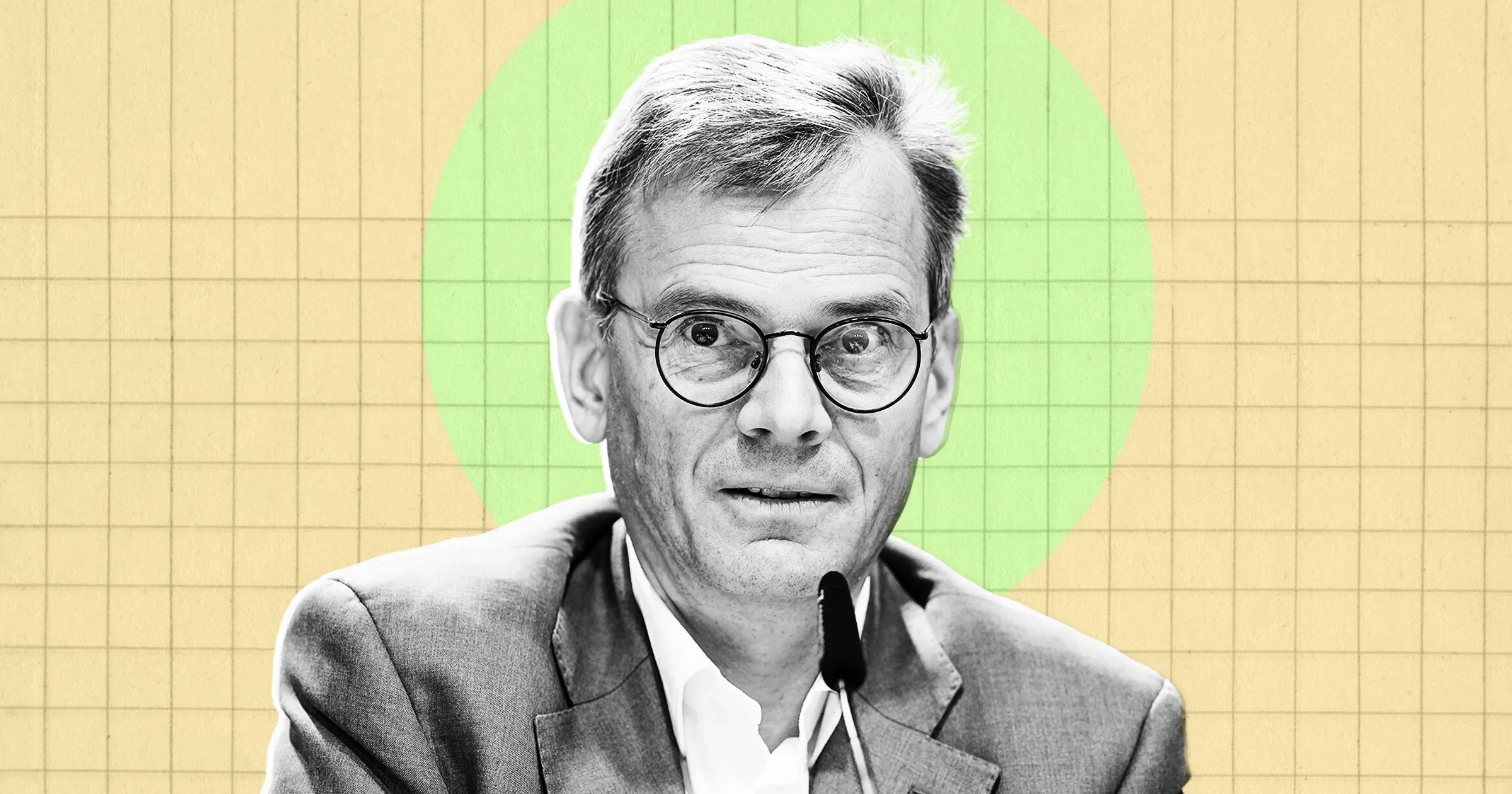

In an interview with the SABC, SAHRC chairperson Chris Nissen said the commission has noted concerns from South Africans complaining about not receiving adequate care in public healthcare facilities due to the overburdened system allegedly caused by foreigners.

“It concerns us [that South Africans believe we are protecting illegal foreigners]. Unfortunately, our constitution is very clear that we need to protect the rights of all people in South Africa,” he said.

Illegal immigrants ‘should not be here drug trafficking’, said Firoz Cachalia.

“The fact is we are not protecting illegal foreign nationals. We are protecting people in this country, and we are looking after our citizens,” he said, stressing that the commission shouldn’t be accused of protecting illegal foreigners and that the responsibility to ensure all people in the country are in the country legally lies with law enforcement and the home affairs department.

“Our home affairs need to do their work. People are accusing the commission and saying foreigners are being served more than South Africans. People are accusing us of protecting foreign nationals. Our act says we must protect the rights of our people, but it doesn’t say we can allow any illegal activity. If there’s any illegal activity, the police must take their course, relevant government institutions must take their course and do whatever they have to do to stop illegal activity.”

Nissen added that borders need to be protected to stop the influx of illegal foreigners.

“We are dealing with the end of the problem. Our border management and home affairs are not doing what they are supposed to do. I’ve visited so many borders, and there’s no border fencing; people can just walk across, come in, and do whatever they want to do.”

Yet, section 27 of the South African Constitution promises healthcare for all, without discrimination. Doctors, bound by oath, echo the same. Yet at hospital gates, Dudula enforces its own constitution: one of violence, intimidation, and exclusion.

The Department of Health has condemned these disruptions, calling them unlawful. Police have occasionally arrested Dudula members for storming clinics, only to release them on bail. The cycle continues: mob, arrest, release, repeat. The state’s condemnation, therefore, rings hollow in the ears of those still chased from wards.

For most Nigerians, the betrayal cuts deep. They migrated to South Africa as students, traders, and professionals. They built shops, paid rent, and contributed to the urban hum. Yet in return, they are subjected to slurs, random beatings, and are now denied medical treatment.

Why xenophobia thrives

South Africa’s rage has roots. Xenophobia, argued doctoral major Bastien Dratwa, has a long and bloody history in post-apartheid South Africa. Social media has enabled anti-immigrant movements to reach larger audiences, harass migrants digitally, and organise across geographic boundaries. As elections approach in South Africa, xenophobic political rhetoric has intensified through online anti-immigrant movements like Operation Dudula and Put South Africans First. Without long-term strategies against the proliferation of hate speech and a pervasive anti-immigrant discourse, violence against migrants will be a hindrance to the socio-economic transformation of South African society, notes Dratwa.

There is no gainsaying that xenophobia in South Africa stands out for its particularly violent nature. According to Witwatersrand University’s Xenowatch, xenophobic attacks resulted in 669 deaths, 5,310 looted shops, and 127,572 displacements between 1994 and March 2024. In May 2008, attacks took place in at least 135 locations across the country. The perpetrators of such attacks did not target white people but rather migrants from other African countries and to a lesser degree from South Asian countries, whom they blamed for increased crime and the high unemployment rate in South Africa.

Yet, amid the widespread sentiments of disillusionment and inequality, politicians fan the embers. Foreigners become scapegoats as the ruling elite, eager for easy applause, point fingers outward rather than inward.

Some political actors have tacitly approved of or encouraged xenophobia by accusing non-nationals of being criminals or pitting them against South African locals. On August 1, 2019, for instance, Community Safety Gauteng Member of the Executive Council, Faith Mazibuko, accused foreigners who fought back during a counterfeit goods raid in Johannesburg Central Business District of being “ungovernable” and striving “to turn the country into a lawless Banana Republic.”

Gauteng premier David Makhura also contributed to the us-versus-them narrative by tweeting, “We are cleaning up our Central Business District. We will not rest until we take our city back” as he joined police in counterfeit goods raids on August 7, 2019 that resulted in the arrests of hundreds of undocumented foreigners.

The statement he released the following day appeared to pit South Africans against foreigners, stating that “as South Africans we must work collectively to build our economy.”

Then, in the same month of that year, the Johannesburg Mayor Herman Mashaba blamed undocumented foreigners for the shortage of medication, saying that “unfortunately we cannot send them back…we have got to treat them.”

Furthermore, on October 26, 2019, he tweeted a photograph of a breakdown of arrests of non-nationals from Malawi, Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. The numbers of arrests spanning from 2016-2019 in Johannesburg, were high but were mostly for driving under the influence of alcohol. He did not reveal the number of arrests of South Africans, or of European, Asian or other foreigners, recklessly misrepresenting the picture of crime in the city and placing blame on African foreigners.

Following xenophobic riots and attacks in Diepsloot in January 2020, Home Affairs Minister Motsoaledi, said, “Most people are not documented because they came here to commit a crime. They came as criminals, not as migrants. The fact that people just remain here and kill police, it is because they don’t want to be seen, and they don’t want to be known. They don’t want their fingerprints to be captured. Don’t confuse them with migrants.”

Such language, no doubt, leaves all non-nationals susceptible to attack. The narrative hardens as foreigners are seen by larger segments of the citizenry as criminals and parasites. These sentiments have spread through Diepsloot, Port Elizabeth, Soweto, Gauteng over the years. Migrants have been robbed and beaten; their shops looted and torched, while the police often stood by, indifferent or complicit.

One migrant recalled reporting robbers to police only to be told: “My brother, I don’t want to die for your safety.” Another watched officers smoke his cigarettes and sip his drinks after his shop was burned.

Consequently, many African migrants live in fear. In Limpopo, Eritrean traders were chased from their homes as their shops got looted and burned to ash. In Soweto, spaza shops worth millions were destroyed in broad daylight and in Orange Farm, foreigners were robbed seven times over while local shops stood untouched.

Nigerians on the receiving end…

Few Nigerians will forget in a hurry, the South African assault on immigrants, in 2019. The attack started from the suburbs of Johannesburg on Sunday, September 1, 2019.

By Monday, September 2, South African men and women wielding clubs and stones were marching through the central business district chanting war songs. In the melee, they looted and burned more than 70 businesses owned by Nigerians, Zimbabweans, Mozambicans, among others, to the ground.

In the wake of a previous attack few months earlier, precisely July 2019, the then President of the Nigerian Senate, Ahmed Lawan, condemned the persistent attacks and killings of Nigerians in South Africa, warning that further attacks won’t be tolerated.

Lawan, who hosted the South African High Commissioner to Nigeria, Bobby Moroe, said at least 118 Nigerians had lost their lives in xenophobic violence over the years, including 13 allegedly killed by the South African police.

“These killings must stop,” the Senate President said even as he cautioned that the circulation of graphic images of victims on social media could spark reprisals beyond the control of government, urging the South African leadership to urgently protect Nigerians living in the country.

Lawan recalled Nigeria’s role in South Africa’s anti-apartheid struggle, stressing that it was unacceptable for Nigerians to continue to die violently in South Africa given their history of helping the country in its time of need.

Nigeria repatriated more than 600 citizens from South Africa following the spate of deadly xenophobic attacks that left at least 12 people dead and scores of businesses destroyed.

The violence, which erupted in Johannesburg and Pretoria, targeted nearly 1,000 foreign-owned businesses and drew international condemnation.

Predictably, the attacks strained relations between Nigeria and South Africa, triggering diplomatic protests and calls across Africa for boycotts of South African interests.

In his remarks, Moroe expressed regret over the killings and conveyed his government’s condolences to the families of the victims. He said an inquest had been launched to investigate the xenophobic attacks and identify lasting solutions.

“Our government will continue to be committed to the good relationship with Nigeria,” Moroe said. “On behalf of the government of South Africa, we express our sincere condolences to the Nigerian government for this unfortunate incident.”

Yet, that grisly history is about to repeat. Against the backdrop of Operation Dudula’s campaign, the anti-immigrant rhetoric escalates like wildfire, threatening to ignite classrooms as it has ignited clinics.

From public officers to private citizens, many South Africans have lent legitimacy to the brewing xenophobic fervour. Some accuse migrants of turning Johannesburg into a “banana republic.” Others blame them for medicine shortages, crime surges, and even the instability of the state itself.

Evidently, their words are tinder, Dudula simply strikes the match.

Culprits must be arrested, prosecuted – Dabiri-Erewa

In an exclusive chat with The Nation, the Chairman/CEO, Nigerians in Diaspora Commission (NIDCOM), Hon. Abike Dabiri-Erewa, assured that all hands were on deck to resolve the crisis.

Dabiri-Erewa declared the imperative for immediate intervention, and urged the African Union (AU) to intervene in the renewed xenophobic attacks on some Africans – including Nigeria – by South Africans seeking to prevent them from accessing medical care.

She said that the renewed attacks of Africans in South Africa have been confirmed in one or two viral videos.

“This is an issue that the AU has to strongly take up. The attack is targeted at Africans not just Nigerians. Though, President Ramaphosa has spoken strongly against this, the AU has to intervene urgently,” she said.

Meanwhile, she said that the Nigerian High Commission in South Africa has appealed to Nigerians to be calm and not take laws into their hands while “we urge South Africa government to apprehend and prosecute those found culpable and citizens openly seen carrying out these xenophobic attacks.

Dabiri-Erewa recalled that both Ministries of Foreign Affairs of Nigeria and South Africa are working on finalising the early warning signal mechanism which is aimed at protecting Nigerians in South Africa from any form of attacks.

Ghosts of Johannesburg

There is no gainsaying that Johannesburg wears two faces. To some, it is the city of gold, a metropolis brimming with opportunities. To others, like Muyiwa, it is a haunted tract, where every corner conceals knife-like memories.

Until she relocated to Canada, Muyiwa dreaded something as mundane as a harmless stroll through the street. There was the possibility of being mauled to death by an irate mob, just like her Zimbabwean and Malawian friends who got butchered by neighbours laughing maniacally as they swung.

Their individual experiences depict the collective fate of many: Obi’s estrangement from his wife, Shoile’s torched auto dealership, Muyiwa’s PTSD, and their collective dread of suffering a fatal death.

Together, they present a composite portrait of Nigerians living in South Africa.

Like ill fated travelers, forced on exile within an exile, each migrant lives with the fear of being attacked. Those who are yet to embrace the trauma of living in a hostile community, startle to the surge of irate mobs shoving pregnant women and nursing mothers cradling newborns out of the hospital corridors on to the sidewalks.

For many migrants, the realism is jarring: they either return to Nigeria and a life of struggle, or remain in South Africa to brave hatred and the possibility of a bitter death. For anyone, either choice is a wound.