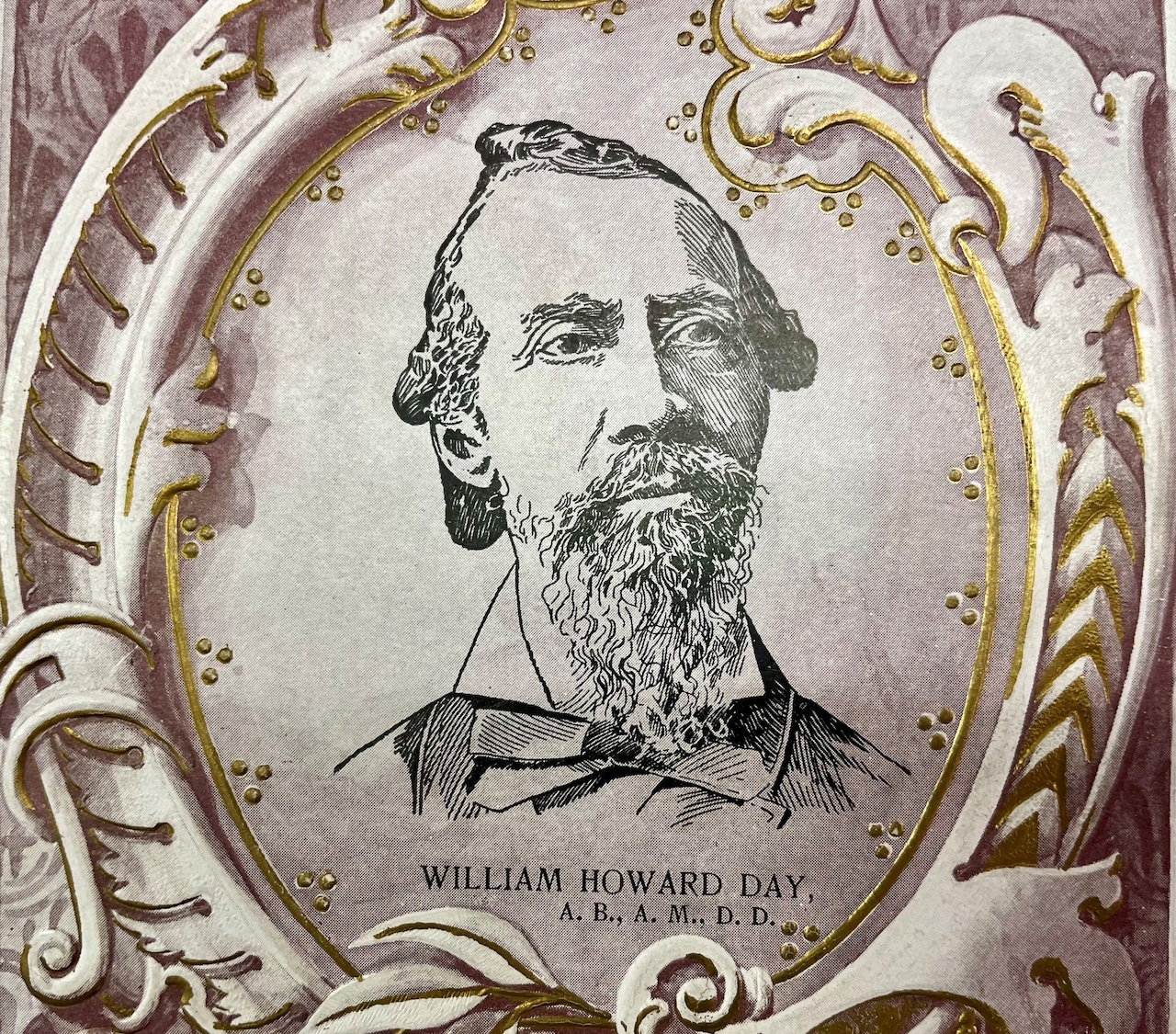

William Howard Day, Harrisburg’s first Black school board president, was born 200 years ago | Column

It was unanimous.

The Harrisburg Board of Control, or school board, elected William Howard Day president in October 1891.

It was a historic moment in Harrisburg and beyond: Day was the city’s first Black school board president, a rarity anywhere in those days.

Day was more than qualified: master’s degree from Oberlin College, tutoring freedom seekers in Canada in the 1840s and 1850s who had escaped slavery in the United States, superintendent of Black schools in Maryland and Delaware in the Freedmen’s Bureau from 1867 to 1871, not to mention currently serving his fourth term on the school board. He had even served as interim president for about three months in 1890.

And the symbolism of a Black man’s elevation to president was not lost on the school board.

“(Day) is … a shining example of the intellectual capabilities of that hitherto oppressed people,” said the colleague who nominated him, “and a living illustration that all races of men are born equal, and given the same advantages, can attain the same plane of intellectual culture.”

For Day, becoming president was another step in his lifelong fight for racial equality.

“By our necessary relationship to the poor and the lowly, in that we are striving to lift the lower stratum of society, so that all society shall be lifted with it,” Day told the school board,” we know no rich, no poor, no bond, no free, no black, no white, but we know humanity, which must be lifted by educational training to higher places of useful life, and that is our mission.”

Thursday marks the 200th anniversary of this pioneering Harrisburg civil rights leader and educator’s birth.

A varied life

Day’s accomplishments went beyond education.

Born in New York City to a father who was a sailmaker and a mother who was active in the African Methodist Episcopal Zion’s mother church, Day’s father died when he was young. Day was adopted at age 12 by a white abolitionist couple in Northampton, Massachusetts.

According to historian Todd Mealy in his biography of Day, “Aliened American”:

Day was an abolitionist, joining the Colored Citizens League, an early civil rights group; becoming involved with the Underground Railroad; and lobbying the Ohio General Assembly for Black rights.

He was a journalist and publisher, starting several short-lived newspapers and printing the constitution for the country radical abolitionist John Brown planned to form if his raid on Harpers Ferry had been successful.

He lived in the United Kingdom from 1859 to 1863, raising money for Canadian settlements of former enslaved people and giving lectures in support of abolition.

He gave a keynote address in the first civil rights demonstration at the U.S. Capitol, on July 4, 1865. Months later in Harrisburg, he was the main speaker at the grand review of U.S. Colored Troops who served in the Civil War.

He was a minister, ordained as an elder in the AME Zion Church in 1866 and served the denomination in a variety of ways, including as secretary of the general conference, leader of the Sunday school association and interim pastor in Harrisburg and York.

He was Pennsylvania’s first Black state worker, serving as clerk in Auditor General Harrison Allen’s office from 1873 to 1876. Day seemed to use his influence to secure a state appropriation for Black schools such as Lincoln University, historian Eric Ledell Smith notes in a paper in the Historical Society of Dauphin County’s archives.

Day moved to Harrisburg permanently in 1873, settling in the Old 8th Ward, a largely Black and immigrant neighborhood near the Capitol. He added a cause: racial equality in Harrisburg schools.

On the school board

Elected to the school board in 1878 — the board’s first Black member — Day campaigned to integrate the city’s segregated schools. No Black students attended the city’s two high schools, and the district had few African American teachers.

That changed in the 1878-79 school year, Mealy writes, when John P. Scott and William H. Marshall enrolled in the Boys’ High School and three unidentified Black students entered the Girls’ High School. Pennsylvania officially integrated its schools in 1881.

Among his other actions on the school board, Day led an effort to provide night schools for students who had to leave school early during the day to work, and he helped end corporal punishment, enact truancy reform and improve the quality of teaching.

Under his leadership — the board unanimously reelected him president in 1892 — the board voted to provide free textbooks to all students and extended the school year from six to seven months.

His last notable act as president was dedicating the city’s new coeducational high school, Harrisburg Central at Forster and Capital streets.

‘To the training of mind without bigotry’

More than 1,000 people crowded into the assembly room of the new high school for the dedication in June 1893.

In a speech frequently interrupted by applause, Day expressed his egalitarian philosophy of education.

He dedicated the new high school to “the inculcation of the principles of freedom, justice and equality; from whatever quarter of the globe we may have come, we shall meet here as Americans; to the promotion of true liberty, true virtue, true independence as sons and daughters of Pennsylvania; to the training of mind without bigotry; to the teaching of letters without pedantry; to the instilling of moral principles, without sectarianism; to the making of intelligent American citizens … .”

Day decided not to seek a new term leading the school board in 1893, and the board was reconfigured less than a week later. His presidency came to an end.

Day continued to serve on the school board until 1899, a total of six terms.

He died Dec. 3, 1900, at age 75. Since his death, his name has lived on in the Harrisburg area.

A federal housing project in Harrisburg and a cemetery in Swatara Township bear his name (although he is buried in Lincoln Cemetery in Susquehanna Township).

He is depicted in a monument at Fourth and Walnut streets in Harrisburg commemorating the Old 8th Ward.

The Pennsylvania School Boards Association hands out the William Howard Day Award to people and organizations for their contributions to public education.

That’s fitting.

Education was at the center of his life’s mission.

As he told a Harrisburg audience in a speech capping a five-day celebration of his life of public service in 1898, the Black teachers who were hired during his time on the school board taught their students “to treasure education.”

“And that, you see,” he said, “was the greatest lesson I ever learned.”