By Jane Cai,Nora Mankel,Sylvie Zhuang

Copyright scmp

This year marks half a century of formal diplomatic relations between China and the European Union as well as the 25th anniversary of the founding of the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China. The fourth in a series of reports examining ties between the two powers reveals a shift underway in the attitudes of younger Europeans towards China and the opportunities it offers.

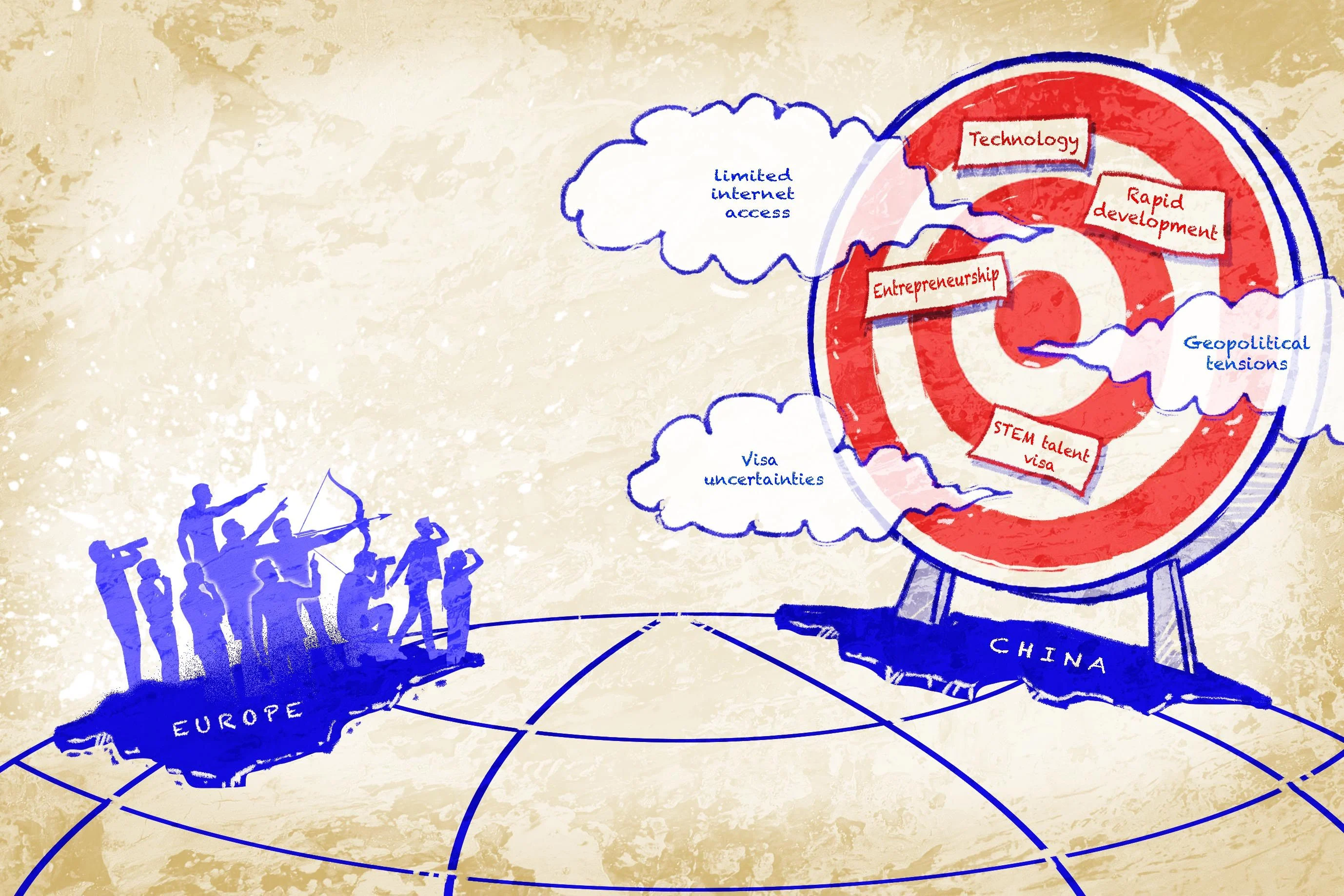

More than two years after stringent Covid-19 restrictions prompted an exodus of foreigners from China, there are emerging signs that Europeans are cautiously rekindling interest in pursuing opportunities in the country, despite challenges such as visa uncertainties, limited internet access and geopolitical tensions.

For many Europeans eyeing global opportunities, China brims with great potential in technology, entrepreneurship and other aspects.

“It’s not just about career growth but also about being part of a system where things are changing fast,” said Simon Wold, a Swedish student doing his master’s in European intellectual property (IP) law at Stockholm University.

According to Wold, working in China, a country where IP protection still has room to develop, is “far more exciting” than staying in the European Union (EU) where everything is already settled and rigid, although he admitted to being something of an an “outlier”, as most of his peers in the niche field of IP law were more keen on Germany, Britain, the United States or France.

There also seemed to be an age divide in outlook, Wold suggested.

“Among younger people I’ve spoken to, the idea [of working in China] is appealing. They see Shenzhen’s rise, Shanghai’s infrastructure and China’s pace of growth and are curious,” he said.

“Older people I’ve spoken to tend to warn me against it, saying China is polluted, poor and a developing country, but I think their image of China is stuck in the 1980s. When I’ve shown them what modern China actually looks like, they’re usually shocked to the core.”

Inspired by a polyglot YouTuber, Wold started to learn Mandarin in 2018, seeing Chinese “as the language of the future, especially when China is key in trade, technology and business”.

“Since I’m studying European intellectual property law, being able to combine that with Mandarin will give me an edge in bridging EU-China relations in this field,” he said.

The relationship between China and the European Union has evolved significantly since diplomatic ties were established in 1975, with annual trade surging by more than 300 per cent since then. In recent years, however, the robust economic partnership has become increasingly strained by political tensions, trade imbalances and differing values.

Chinese President Xi Jinping has pledged wider opening up this year to boost cooperation with the 27-nation bloc, describing China and the EU as the two “constructive” powers in the world amid growing US-China tensions.

The effort has focused on traditional areas like automobiles, machinery manufacturing, energy, chemicals and aerospace, while expanding collaboration in emerging fields such as digital, green energy, biopharmaceutical, artificial intelligence (AI) and quantum technologies.

Many Europeans are excited about the opportunities, but factors such as restricted internet access, uncertainties over securing visas and concerns about the politicisation of business are significant considerations.

Alain Saas, a French national who founded a Canada-based AI start-up, expressed unwavering enthusiasm for working in China. “Yes, 1,000 per cent,” he said, when asked if he wanted to live in China to ride the tech wave.

However, Saas has chosen to relocate to Japan as he lived there before and it is close to China. He has also yet to find an opening in China and is concerned about issues such as internet restrictions there.

“The technology [in Japan] does not represent the future as much any more, unlike when I first moved there in 2010, and I would be much more excited by the future in China,” he said.

China has achieved remarkable progress in technology and innovation, transforming into a global powerhouse in areas like AI, robotics, quantum computing and renewable energy, thanks to years of massive state-funded research and development and a strong manufacturing ecosystem.

Still, Saas is bothered by Beijing’s Great Firewall, which blocks access to many foreign websites and apps and slows cross-border traffic, and the uncertainties for foreigners trying to obtain long-term visas or residency status.

It just took him three weeks from application to receiving a five-year highly skilled professional visa for Japan. After working there for one year, someone of his category can obtain permanent residency, with the same rights as a Japanese citizen, except for voting, he said.

“Paperwork costs nothing, is super easy and I get my residency card on arrival at the airport,” he said, adding these things could be more complicated in China, citing experiences shared by his friends.

According to China’s immigration regulations, foreigners who have held senior positions – such as deputy general manager or an equivalent role – for at least four consecutive years, and have lived in China for at least three years with a good tax record, are eligible to apply for permanent residency.

Those who have made significant and outstanding contributions to China or who are urgently needed by the country are also eligible.

But getting a visa to live in China as a foreign entrepreneur is not easy. The application process is complex, requiring navigation of local regulations and submission of extensive documentation, including employment contracts and proof of qualifications, all of which then undergo thorough scrutiny by the authorities.

In a bid to attract top global talent and strengthen its innovation ecosystem, China is introducing new measures aimed at easing entry for skilled professionals in science and technology.

Last month, Beijing announced a new category of K visas for young science and technology talent from overseas, taking effect on October 1.

Eligible applicants include STEM graduates from recognised universities or research institutions worldwide holding at least a bachelor’s degree, or young professionals engaged in relevant education or research work at such institutions.

There is no requirement for a Chinese employer or inviter at the application stage.

Holders of K visas can be engaged in education, research, cultural exchange, entrepreneurship or business in China.

While the detailed implementation guidelines have yet to be announced, Hong Kong-based business consultancy Dezan Shira & Associates expects the K visa to offer greater flexibility regarding the number of entries permitted, validity period and duration of stay.

Sean, an Irish national who asked that only his first name be used, said the K visa concept was good and fit well into China’s broader talent attraction strategy. However, he added that the success of the programme would depend on its practicality and implementation.

“To some degree the appeal of China has dropped due to China-US decoupling, foreigners’ experience during the Covid lockdown and a perceived lack of work-life balance,” the Dublin resident said.

Still, Sean said he would love to work in China, particularly in Shanghai – because of its vibrancy and quality of life.

“In my sector – biotech pharmaceuticals – the innovation coming out of China now is quite remarkable, a bit like AI but is less well known, and I like the people of China, so much great food and beautiful places,” Sean said.

According to the most recent official census data, around 1.4 million foreigners were living in China as of November 2020. Of these, 845,000 were in mainland China and the rest distributed among Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.

Most of China’s foreigners are drawn to the big cities. But between 2010 to 2020, the number of immigrants fell by more than 21 per cent in Shanghai and 41.5 per cent in Beijing, as many left the country during the stringent zero-Covid policies, which included strict travel restrictions and lockdowns.

Many of those who left did not return after China reopened its borders in early 2023. Shanghai was home to 72,000 foreign workers at the end of 2023, according to official data. That was about one-third the number who were working in the Chinese financial hub in early 2019, according to a report by Jiefang Daily, a publication affiliated with the Communist Party.

Higher living costs and escalating geopolitical tensions between China and the West have also contributed to a decline in the number of Western expats working in major Chinese cities.

Ioana Kraft, human resources working group chair at the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China, welcomed the introduction of the K visa but cautioned about details still to be worked out in terms of education and work experience requirements, as well as age restrictions.

“We need more clarity about the permitted activities for K visa holders [and which] entrepreneurial business activities are suggested to be allowed. But we need to see if they [can] come in if a business has been started, or can they [only] come into the country on that visa and then start the business here?” Kraft said.

“So there are still lots of question marks. Although in principle, it’s always a step forward to attract foreign talent and make it easier for them to come.”

Kraft also expressed concerns about Europe’s deteriorating perception of China, partly due to the “politicisation of business”, as seen in the recent exit ban imposed on an American banker, she said.

China confirmed in July that it had barred a senior Wells Fargo executive from leaving the country because of a “criminal case” investigation.

Reports earlier said that Chenyue Mao, an Atlanta-based managing director at the American banking giant and a US citizen, had been prevented from leaving China. Wells Fargo has since suspended all business travel to China.

“Some CEOs are even reluctant to come into China for a short period because they are afraid if there is a legal dispute that involves their companies, they may not be able to leave the country,” said Kraft, who has lived in Shanghai for 22 years.

In addition to limited internet access and high living costs – as much as 400,000 yuan (US$11,000) for international school tuition, for instance – many companies now require fewer foreigners in China because the domestic workforce is just as capable of filling key roles, she added.

Cameron Johnson, a US citizen and senior partner at business consultancy Tidalwave Solutions in Shanghai, said that local talent had caught up in many ways.

“Having an expatriate here is incredibly expensive. Because the local talent gap has shrunk so much, you could actually hire two or three seasoned Chinese [staff instead],” Johnson said.

But he also emphasised the great career opportunities in China for expats, saying that this was because it was in many aspects the centre of the world for technology, manufacturing and supply chain integration, or for R&D.

“If you are in EVs [electric vehicles], semiconductors or rare earths or biotechnology, China is the leader, or No 2 in all those areas. You have to be here. If you are not here, then you will fail as a company,” he said.

“And so that is why China, in many ways, is still positive. Then there are of course many challenges, but the government is still very supportive of developing the industries of tomorrow and today.”