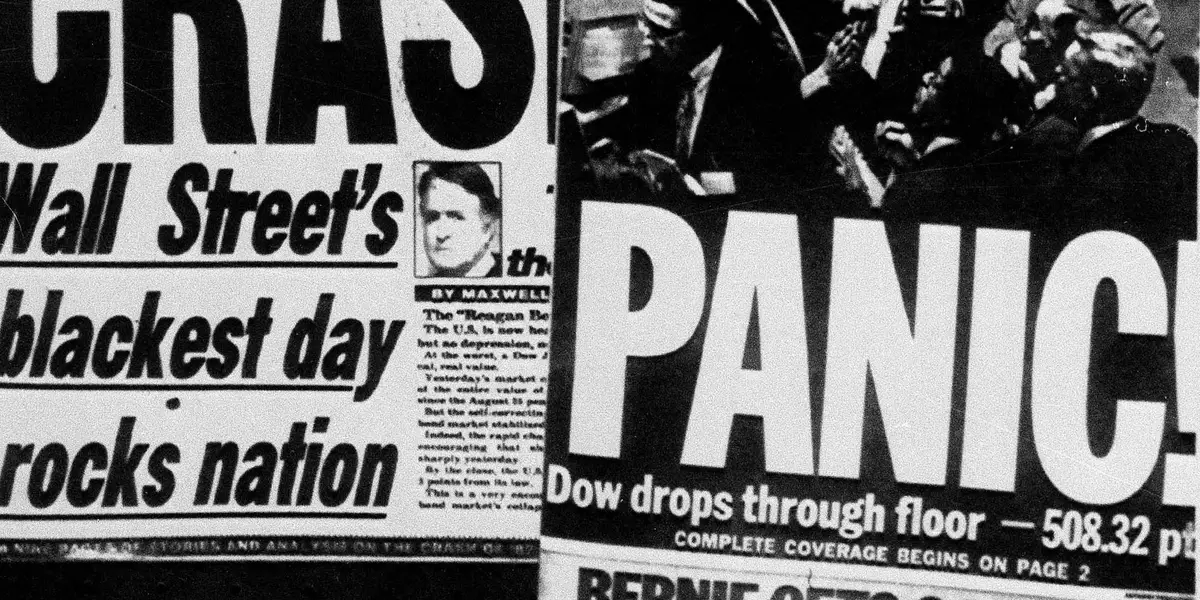

Yale economist William Goetzmann has felt the fear that a stock-market crash can strike into an investor. He’s lived through at least four of them: 1987, 2000, 2008, and 2020.

“I watched my entire life savings drop by 50% during the crash of 2008,” he told Business Insider earlier this month.

Many Americans who had money in the stock market at the time saw similar losses. It’s the kind of scarring experience that can make an investor paranoid that another crash is always around the corner.

And it apparently has, as Goetzmann’s research has found that fear of a rapid decline is pervasive among investors. Since 2000, respondents to Goetzmann’s surveys at any given time have generally said there’s a 10%-20% chance of a crash in the next six months.

“What our research suggests is they can be reacting to even things that aren’t having to do with the stock market,” he said. “Like if there’s a big earthquake nearby, they tend to think there’s a higher probability of a crash.”

Today, there seem to be heightened fears of a market bubble — and a subsequent pop — with AI stocks fueling an 86% surge over the last few years and the S&P 500’s Shiller CAPE ratio at its third-highest level ever.

While these concerns are understandable in some sense, they also defy the data, Goetzmann said. His research has found that stock crashes after big surges don’t happen all that often to begin with, and when they do occur, they don’t last that long.

Related stories

Business Insider tells the innovative stories you want to know

Business Insider tells the innovative stories you want to know

In a 2016 paper, Goetzmann looked at instances around the world since the 1880s when a country’s market has surged by 100% over a one-year period or a three-year period. In those cases, stocks have ended up down by at least 50% in the following year or five-year period less than 1% of the time. In fact, 26% of the time, the market has risen another 100%.

In some ways, Goetzmann’s research is narrow and doesn’t account for all downside scenarios. For example, it wouldn’t account for the S&P 500’s roughly 49% in the two years after the dot-com bust from 2000-2002, as the market was down about 18% in 2005, five years after its peak. Yet this is widely looked at as one of the most damaging crashes in market history, as it took investors years to claw back the deepest losses.

It also doesn’t account for the fact that crashes tend to arrive alongside recessions, and those who end up unemployed may be forced to sell their stock holdings near the bottom to meet liquidity needs.

But if you have a long-term time horizon and are able to stay invested, Goetzmann’s message is simple: even if the market crashes, it’s highly unlikely that vast swaths of your wealth will be gone if you just ride it out for five years.

“If you wait five years after this event, you’re going to be better off. That’s what I’m telling you,” he said. “But you can say, ‘Look, we’re a small college endowment, and we depend on our endowment to pay the salaries of all the staff, so I just can’t wait five years.”

These days, Goetzmann is worried that investors’ fearfulness is getting worse, which will keep people out of the market and rob them of future returns.

“In this day and age, we’re being shocked all the time when we get on the internet or watch television with scary things,” he said.

“So one concern that I have is that if people are generally more fearful of a terrible event, they might be more fearful of the stock market crashing as well, and they might not even invest in the stock market,” he continued. “They might say, ‘Well, I’m just going to stay on the sidelines because the bottom could drop out of the stock market tomorrow and I wouldn’t have any savings left.'”

But Goetzmann himself knows the benefits of taking a calm approach and staying invested.

In all four crashes Goetzmann has seen, he’s kept his money in the market, eventually benefiting from the long bull-market surges that have followed steep declines.

In 2020, “that spring was quite scary,” he said. “But I held my breath and just said, ‘Well, I’ll stick with what the long-term data show us about the stock market.'”