Copyright Anchorage Daily News

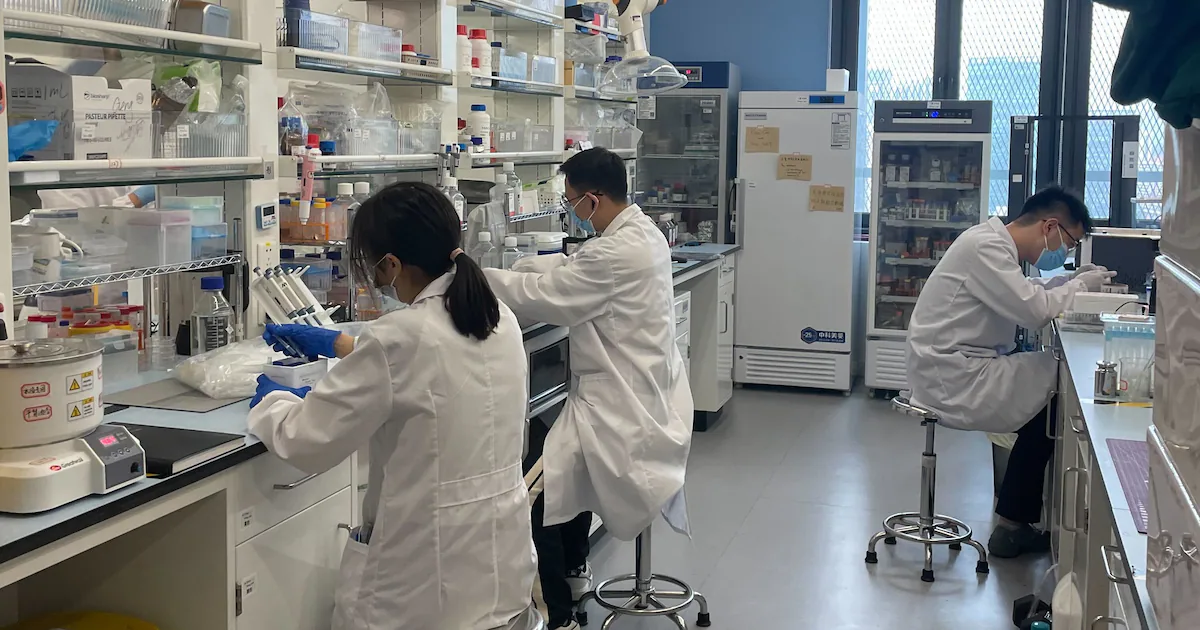

SHENZHEN, China - When Stephen Ferguson, a 35-year-old New Yorker, walked into a conference room here in June, he was shocked to find 50 people from China’s top scientific institution eager to hear about his experience working in this southern Chinese city. Ferguson was recruited in 2023 as a biology researcher - despite having only been to China once before - and the delegation from the prestigious Chinese Academy of Sciences wondered what could be done to make the research environment first-rate. The fact they wanted to hear from “some random guy from the U.S.” symbolized something much larger to him: “I feel like I’m in an environment where science is really being promoted - it’s growing, and they’re attracting a lot of talent,” he said. “They are making it easy to say yes.” Ferguson is far from the only American scientist saying yes. Over the past decade, there has been a rush of scholars - many with some family connection to China - moving across the Pacific, drawn by Beijing’s full-throttle drive to become a scientific superpower. But Donald Trump’s return to the White House has turbocharged this effort. The Trump administration has cut billions in science funding, canceled grants for some of America’s most elite universities, revoked international student visas and hiked up costs for highly skilled H-1B visas. The slashing of science funding, combined with the increased scrutiny scientists of Chinese descent have faced in the United States, has boosted Beijing’s efforts to attract top-tier talent and cement its position as a center of global science. More than 70% of these departed scholars work in STEM fields, and the most dramatic shift occurs in engineering and life sciences, the Princeton data shows. Those who’ve moved to Chinese universities this year include a senior biologist at the U.S. National Institutes of Health, a world-renowned Harvard statistician and a clean-energy scholar who worked for the U.S. Energy Department. Just this week, Westlake University in Hangzhou announced that renowned scientist Lin Wenbin, formerly the James Franck Professor of Chemistry at the University of Chicago, had joined its faculty. Scientists in both countries say this scientific migration will have significant implications for the global research ecosystem and the increasingly fierce U.S.-China technology competition, chipping away at the U.S.’s competitive edge and making it more likely that the next generation of vaccines or artificial intelligence models will come out of China. “The U.S. is increasingly skeptical of science - whether it’s climate, health, or other areas,” said Jimmy Goodrich, an expert on Chinese science and technology at the University of California Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation. “While in China, science is being embraced as a key solution to move the country forward into the future.” The moves also provide crucial propaganda victories for the Chinese Communist Party and help leader Xi Jinping achieve his vision to turn China into a science and technology powerhouse by 2035. “Whoever controls talent ultimately controls the future of the world,” said Zhao Yongsheng, an economist at Beijing’s University of International Business and Economics. Beijing is spending big in its recruitment drive: The National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), the central scientific research funding agency, is devoting an increasingly large share of its $8 billion annual budget to talent programs. Individual provinces, cities and universities are rolling out the recruitment red carpet. Beijing also introduced a new K visa last month to attract young, foreign STEM talent. The visa has, however, been controversial, especially among young graduates who don’t want foreign competition as they struggle to find work in a tough economy. Although the U.S. maintains many advantages as a long-standing global research hub and is still a magnet for many ambitious scientists, China is rapidly catching up. Twenty years ago, the U.S. spent almost four times as much as China on research and development. But by 2023, China had almost closed the gap: R&D spending across the U.S. government and private sector totaled $956 billion, only slightly more than China’s $917 billion, according to the American Association for the Advancement of Science. The key question is whether this funding turns into scientific gains - and whether these transplant scientists will deliver breakthroughs in China’s vastly different, and politically constrained, environment. Push and pull Beijing has long sought to attract scientists, particularly those who were born in China, through programs like the Thousand Talents Program, a high-profile state-run initiative that financially incentivized top academics to bring their expertise to China. Patriotism, and a desire to contribute to Chinese science, has motivated some to return. For instance, Jun Liu, a Chinese-born Harvard statistician who was appointed a chair professor at Tsinghua University in September, said in an interview that he “can play a bigger role here” and “raise the standard of statistical research in China.” But it feels to some like Washington is now actively trying to push out scientists as well. When Jonathan Kagan, an immunologist at Harvard Medical School, attended a conference in Suzhou in May, he said Chinese scientists kept telling him the same thing: “We hope Trump is president for life, because it is the best thing to happen to Chinese science.” For scientists of Chinese descent in the U.S., the concerns are particularly pressing. In 2018, the U.S. government launched the China Initiative, which investigated researchers in the U.S. for ties to Beijing. The program led to a big spike in departures among Chinese American scientists who felt unwelcome at U.S. universities, even after the Biden administration canceled the initiative in 2022. The push to leave the U.S. doesn’t just impact scientists with family links to China. The Harvard nanoscientist Charles Lieber, one of the most high-profile targets of the China Initiative, was convicted in 2021 of falsifying tax returns and failing to report foreign finances. This April, he became a full-time faculty member at Tsinghua Shenzhen International Graduate School (SIGS), the STEM-focused outpost of the prestigious Beijing university. Lieber declined to be interviewed about the move, but at a grand welcoming ceremony in his honor, he said he looks forward to turning “ambitious scientific dreams into reality.” Even those who have long been insulated from funding shocks or political changes are taking note. Terence Tao, a celebrated UCLA mathematician sometimes called the “Mozart of Math,” recently had $26 million of U.S. National Science Foundation grants suspended. Though the grants were later reinstated, Tao, who was born in Australia, said universities in China had since been in touch, trying to lure him there. He never previously considered leaving the U.S., where he has lived for more than 30 years. But the attacks on higher education are forcing him to rethink his assumptions about the U.S.’s ability to sustain science leadership. “I’m not certain about anything anymore,” he said. Shenzhen nexus Nowhere is more central to China’s scientific ambitions than Shenzhen. In the fishing village turned tech metropolis in southern China, researchers from all over the world are being drawn to state-of-the-art research facilities and expanding university campuses, with ample resources and proximity to China’s most innovative companies, like telecommunications giant Huawei. Ouyang Zheng, dean of Tsinghua SIGS, said in an interview that Shenzhen is a “focal point” between education and cutting-edge industry, and a “new industrial engine.” SIGS was set up to fuel that engine. The school - which is aiming to triple its faculty in the next decade - promotes a risk-taking, out-of-the-box learning environment, more akin to a U.S. university, and has attracted plenty of scholars with overseas experience. About 80% of SIGS faculty have taught or researched overseas, including Ouyang himself, who returned to China in 2017 after a long career in biomedical engineering at Purdue University in Indiana. Academic superstars aren’t the only ones who are moving here: Up-and-coming researchers are also putting down roots. Take Alex Liu, 38, a Chinese-born mosquito researcher who earned his PhD at Auburn University in Alabama. “I really didn’t find that many opportunities in America,” he said in his office, where he keeps an Auburn football on his desk. In 2023 - before Trump’s return to office - Liu accepted a position at the Shenzhen Bay Laboratory, a biomedical research institution backed by the local government, where he could also be closer to family. He now runs a team of more than 10 people - their salaries partially covered by the Shenzhen government - studying mosquito biology and disease transmission. Ferguson, the New Yorker, worked with Liu in the U.S. and now is a postdoc on his team. The dramatic move paid off for Ferguson, who said he felt a growing “cultural rejection” of science in America before he left. He receives five funding streams in addition to his salary - which is more than he was offered in the U.S. - to cover research and living expenses, including a grant from Guangdong province and from the NSFC, he said. Chinese institutions also work to make international brainiacs feel special. Foreign scientists and returnees often enjoy other perks like priority access to child care and schooling, and entrepreneurial funding, according to academics in China and job postings. Cultural challenges Even with this special treatment, foreign scientists without previous connections to China face lifestyle adjustments and cultural hurdles. Researchers with long histories in the U.S., for instance, sometimes face suspicion and exclusion from career opportunities, said Zhao, the economist. “As a result, their numbers remain small and their influence limited - often, after some time working in China, they feel constrained and eventually choose to leave.” Scientists also have to contend with China’s restrictive political environment. “In China, scholars’ freedom at work is also constrained, as they are subject to bureaucratic control,” said Yu Xie, a Princeton professor of sociology who led the team compiling the talent flow data. “The university system in China is rigid.” Ultimately, as the two superpowers vie for talent, individual scientists are forced to weigh painful trade-offs between the countries. “They are caught in between,” Xie said. - - -