By The Independent

Copyright independent

Eight African countries, including Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania, participated in the review and committed to fast-tracking national approvals within 90 days

NEWS ANALYSIS | BY AGENCIES | Every year, around 30 million babies are born in malaria-endemic regions of Sub-Saharan Africa.

But until recently, the world’s smallest and most vulnerable malaria patients had no approved treatment designed specifically for them.

The approval in July by Swiss medicines agency Swissmedic of Coartem Baby, the first antimalarial drug formulated specifically for newborns and infants under five kilograms, marks a significant milestone.

But it also raises questions about why it took until 2025 to address this critical gap in care.

The drug was developed through a collaboration between pharmaceutical company Novartis and the not-for-profit Medicines for Malaria Venture.

Improvised doses

For decades, healthcare workers treating malaria in newborns faced an impossible choice — use adult medications at improvised doses and risk causing harm or avoid treatment altogether in the most vulnerable patients.

“Until now, health workers have had to improvise by using low doses of drugs meant for older children and hoping for the best,” Adam Aspinall, senior director of access and product management at the Medicines for Malaria Venture told SciDev.Net.

The standard approach involved breaking up bitter adult tablets or using formulations designed for older children, methods that risked both under- and overdosing.

This treatment gap persisted despite malaria remaining a leading killer of young children in Sub-Saharan Africa and despite the fact that newborns face a particularly dangerous window of vulnerability.

Why the delay?

Several factors contributed to this decades-long gap in paediatric malaria care.

Medical professionals long believed that maternal antibodies provided sufficient protection for newborns for several months.

“There has always been this misconception that newborns were somehow protected for months by maternal antibodies,” explained Aspinall.

“But the data simply doesn’t support that.”

While maternal antibodies offer some protection early in life, that shield fades fast, often within weeks, leaving newborns exposed during a period of extreme vulnerability, according to the MMV.

Newborns have also historically been excluded from drug trials due to ethical concerns and the complexity of studying this population.

“The truth is, babies were excluded from trials because they are seen as too complex,” said Aspinall.

“It’s taken years and new modelling techniques to close that evidence gap.”

Another barrier is that the paediatric drug market offers limited commercial returns compared to adult medications.

“This isn’t going to be a blockbuster drug,” Aspinall acknowledged, “but it is a public health necessity. That’s why it’s being introduced at the same price as existing formulations, on a largely not-for-profit basis.”

Many African countries also lacked robust systems for evaluating paediatric medicines until recently.

Moji Adeyeye, director general of Nigeria’s National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control, told SciDev.Net that Nigeria and others “had to build that capacity almost from scratch”.

Adeyeye, who co-chairs the WHO Paediatric Regulatory Network, explained that few African regulators had frameworks to assess children’s medicines just five years ago.

Baby-friendly tablet

Developing antimalarial drugs for newborns requires addressing unique physiological challenges.

“Newborns metabolise drugs differently. Giving them adult or even standard paediatric doses can be dangerous,” said Aspinall, explaining that infants metabolise medications differently than older children and adults, particularly due to immature liver function, meaning that standard dosing approaches can be dangerous.

Coartem Baby addresses these challenges through a dispersible tablet that dissolves in breast milk, making administration easier for caregivers. It contains doses of the drugs artemether and lumefantrine tailored to a newborn’s metabolism.

“Children will spit it out if it’s bitter,” explained Adeyeye.

“That’s why paediatric dosage forms are far more complex than adult ones.”

She says the dispersible tablet formulation avoids the pitfalls of syrup-based antimalarials that require refrigeration and are vulnerable to microbial contamination.

“In resource-limited settings, a syrup can do more harm than good if not stored properly,” she added.

Regulatory innovation

The approval process itself represents an innovation in global health regulation. Rather than following traditional pathways that might take years, the drug was approved through Swissmedic’s Marketing Authorization for Global Health Products procedure, which involves endemic countries directly in the assessment process.

Eight African countries — Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Uganda — participated in the review and committed to fast-tracking national approvals within 90 days.

“This collaborative approach ensures countries are not just recipients of a decision, they’re active stakeholders,” Aspinall said.

For Adeyeye, the timeline for developing this treatment points to stark disparities in global health priorities.

She draws a pointed comparison to COVID-19 vaccine development: “When a disease affects rich countries, we see action in months. Malaria, which kills poor children in poor countries, took decades. It’s unacceptable, but it’s our reality.”

The approval comes as malaria vaccines like RTS,S and R21 are being rolled out across Africa.

Rather than competing approaches, Aspinall views these interventions as complementary tools in the fight against malaria.

“We need as many tools as we can get,” he said.”Vaccines are a huge step forward, but they’re not yet approved for very young infants. There will always be cases, and we still need treatments.”

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net.

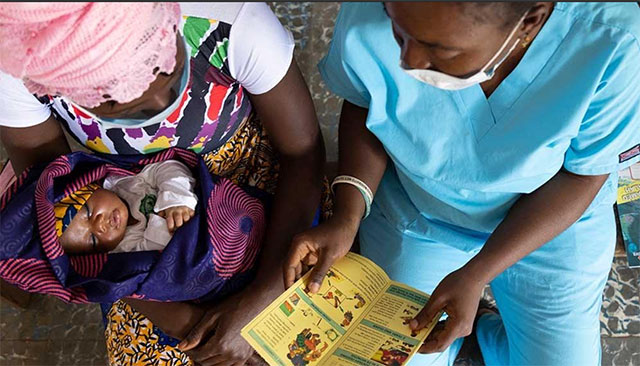

A nurse shares educational materials with mother to protect her baby and family from malaria at Petifu Junction Health Centre in Sierra Leone on 9 August 2021. A new antimalarial drug for newborns highlights a gap in paediatric medicine.