By Carl Jackson

Copyright birminghammail

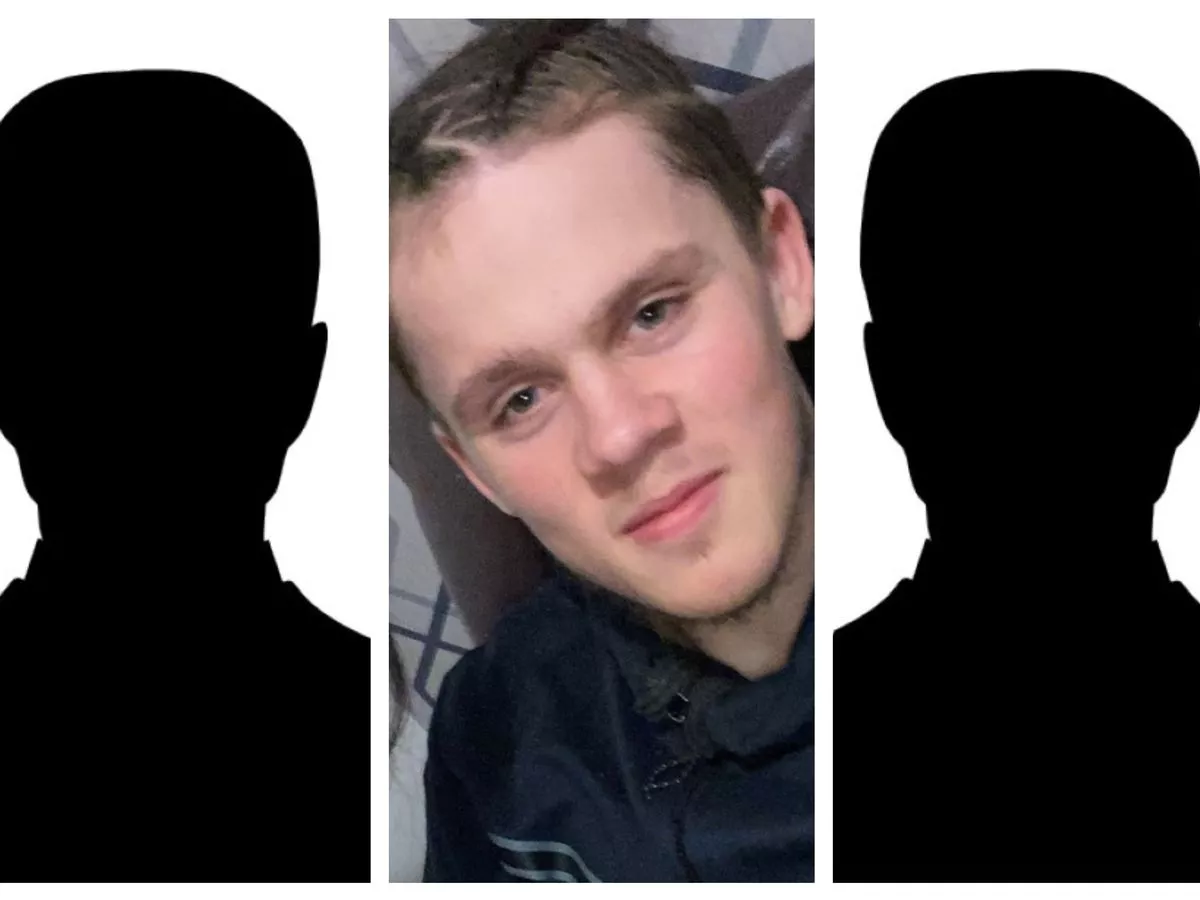

When two 15-year-old boys were convicted of murdering 17-year-old Reuben Higgins in a Solihull vape shop Birmingham Live strongly believed the public should know exactly who they are. We, like everybody else, have had enough of the lives of young men, teenagers and indeed children being needlessly extinguished by a knife. And we say the courts need to send out a strong message to those responsible, regardless of whether they have reached a certain age threshold. As our Deep Cuts campaign recently stated: ‘kids are killing kids’ in Birmingham and ‘change cannot wait’. READ MORE: Killer teen yells ‘I’m still breathing’ as he’s jailed for vape shop murder of boy, 17 And so, we formally applied to Judge Paul Farrer KC, presiding over Reuben’s case, that reporting restrictions preventing us from identifiying the two youngest of his killers, because they were under 18, should be lifted. You may have gathered from the headline of this article that he refused our application. We, of course, respect and understand his ruling. We are certainly not here to criticise the decision of an experienced and highly respected judge. But for anyone bemused and angered as to why the law protects two such individuals, one of whom is a serial violent robber, let us explain. The task for the judge was essentially a balancing exercise between the interests of justice, including the public interest, and the welfare of the defendants. Afterall, rehabilitation is a cornerstone of the UK criminal justice system – even for killers – as opposed to a ‘lock em up and throw away the key’ mentality. Our primary argument was that Reuben’s murder occurred against the backdrop of out of control knife crime in Birmingham, albeit it took place on the other side of the border in Marston Green. It is well-established that young people carry knives out of a false sense of protection when the reality is that decision only increases the risk of harm to others and themselves. In recent times there’s nothing more that underlines the epidemic of knife violence on our streets than the tragic fatal stabbings of 14-year-old Dea-John Reid in Kingstanding in 2021, 16-year-old Sekou Doucoure in Hockley in 2022 and 17-year-old Muhammad Hassam Ali in Birmingham city centre last year. And let us not forget that 12-year-old Leo Ross was stabbed to death in Hall Green in January, with a 14-year-old boy awaiting trial for murder. Shortly after 6pm on October 29 last year Reuben and his friends were confronted by four males. The oldest of them, a man who remains at large, accused him of threatening him with a knife on a previous occasion, and asked Reuben to go around the corner. Reuben refused and the group chased after him, including the two 15-year-old boys and Abdurrahman Summers, who had recently turned 18. They forced their way into Vape Minimarket, where he had lay behind the front door, dragged him up and attacked him. One of the 15-year-old’s stabbed him in the arm and leg while the older man, who initiated the confrontation, delivered the fatal stab wound to his heart. The other 15-year-old ‘assisted and encouraged’ the attack while Summers was also present, albeit he quickly exited the shop shortly after the 10-second assault commenced. Reuben tragically died at the scene. He had been outnumbered, unarmed, defenceless and was pleading for his life. We argued that this was an example of the most serious type of knife crime and one where the courts should send out a clear message to the public about the dangers of carrying and using knives. After being arrested none of the defendants provided an account of what happened or gave evidence at their trial this year. They showed no remorse, we contended. Naturally, barristers for the two youths, who have since turned 16, opposed our application to name them. They told the court their clients had neurodevelopmental issues, difficult upbringings and had been exploited by older people. They also argued that naming them publicly would undermined their safety in custody, their rehabilitation and increase the risk of retribution to their families. There are legal authorities which support both sides. Some emphasise the importance of ‘open justice’ and the deterrent effect of identifying criminals. Others advocate that the welfare of juvenile defendants should be ‘given great weight’ and that reporting restrictions granting anonymity will only be discharged in ‘rare’ cases. To that point one defence barrister argued Reuben’s case was a ‘depressingly familiar story’ with ‘nothing unique or unusual’, at least in a legal sense. In his conclusions Judge Farrer recognised the ‘legitimate public interest’ in reporting knife crime and the deterrent effect of naming individuals. However, he said: “I accept the opinions expressed by the youth offending team to the effect that in each of their cases, naming them publicly would expose them to the risk of both physical and emotional harm and would endanger their rehabilitation.” Judge Farrer stated deterrence would still be achieved by the reporting of the facts of the case, the age of the defendants and their sentences. He therefore ruled it was ‘not in the interests of justice’ to remove the reporting restrictions. Following the decision the court was told that the 16-year-old who had stabbed Reuben in the arm and leg had a previous conviction for theft. The incident came ‘perilously close’ to robbery and involved an accomplice having a knife. The other 16-year-old had previously committed ten robberies or attempted robberies in a single year. Many of them involved a group attack and the presence or threat of knives. In addition, both teenagers were on bail at the time of Reuben’s murder in relation to a separate alleged violent incident. You could be forgiven for thinking both boys were ticking timebombs waiting to go off with deadly consequences. Yesterday, Monday, September 15, they were sentenced to life with minimum terms of 17 years and 15 years respectively. Incidentally, Summers was handed a minimum of 19 years. For now the younger two defendants will remain anonymous. Their cellmates will remain oblivious to what they have done as their rehabilitation takes priority. But here’s the thing. Their reporting restrictions only last until they turn 18. Then, things will be different.