By Matt Alston

Copyright gq

If you’re the parent to a Star Wars–crazy kid who loves LEGO (the Venn Diagram of these two tastes is close to a perfect circle), or a child-at-heart who adores one or both of these brands, you may not know about the LEGO Death Star soon to enter orbit. But for a more devoted subset of LEGO fans, the upcoming playset has been the subject of online rumors, argument, speculation, disappointment, and ire—a hype cycle that’s been churning for almost a year and concludes next week, when LEGO releases its first thousand-dollar set.

Yep. That’s the price. On October 4, you can buy a single LEGO set for the tidy—though certainly not small—sum of one thousand actual US dollars. The long-awaited, oft-rumored, LEGO Ultimate Collector’s Series Death Star is a very large and very expensive toy. The set contains 9023 pieces, weighs almost fifteen pounds, and represents the most expensive plaything in the history of the brand. Technically priced at $999.99, it is also not the largest LEGO set ever (their Eiffel Tower is taller) nor does it have the most pieces (an elaborate LEGO World Map set features 12,000).

It’s not even the first (or third) LEGO Death Star: the brand has made earlier versions of Star Wars’ most famous planet-sized weapon, which retailed in the $300 and $400 range. But this new Death Star represents a scale and ambition from the LEGO group so large, so costly, and so out-of-this-world that it may potentially establish a new paradigm for the types of premium collectors’ products they can make and sell. Or, like its cinematic inspiration, it may become destructive on an unimaginable scale, pushing devotees of the world’s most popular toy to a new breaking point.

Getting a few things out of the way, speed-round style, for the uninitiated: They’re LEGO bricks, tiles, and plates. They’re not blocks, and they’re especially not called LEGOs, plural. There are also gears, elements, jumpers, brackets, bars, flags, and dozens more named types, a dizzying hierarchy of parts.

There are also minifigures. Some LEGO fans are exclusively fans of minifigures, and LEGO will occasionally include a first-time minifigure or character in a large set as an incentive to purchasers. LEGO Star Wars fans are often minifig-obsessed, and many see the strategy of hiding certain minifigures behind the “paywall” of larger, more expensive sets as exploitative and hypocritical. You can later find these exclusive figures on the aftermarket with heavy mark-ups. (The forthcoming Death Star set comes with 7 exclusives, including Rogue One’s Galen Erso, which means the set also marks actor Mads Mikkelsen’s first appearance in LEGO minifigure form.)

The name LEGO has been commonly genericized, like Kleenex and Xerox and Google, and this brand recognition works as part of the business’s protective moat. Even though LEGO’s patent on their system of injection-molded plastic bricks (studs on the top, tubes underneath) expired in 1978, most people commonly refer to any upturned Tupperware of multicolored bricks as LEGO. Brands like Tyco and Mega Bloks may have flooded the market for decades with generic, passable imitations, but no parent has ever cursed the inventor of Mega Bloks after stepping on one in the middle of the night.

In the 1970s, LEGO would release 40 or 50 unique sets a year—tailored assortments of bricks with printed instructions for the building of specific models, like a rudimentary helicopter, windmill, or a train station. By the late 1980s and early ‘90s, LEGO was producing 200 sets a year, with unlicensed, original themes released in quarterly and yearly cycles, products designed around objects and subjects of imagination, like Castle, Space, and Pirates. When business fell into a drastic slump in the 1990s, LEGO was lucky to find and develop a partnership with Lucasfilm, and things began to turn around.

The launch of LEGO Star Wars in 1999 marked the brand’s first movie-IP-licensed sets; LEGO Harry Potter followed in 2001. The more LEGO invested in IP sets, the more the line went up. The brand of imagination found that borrowing other people’s wizards and spaceships was surprisingly good business. IP fans stuck with LEGO as they aged, and over time adding adult business as a focus has helped LEGO conquer the world of children’s toys. In 2015, the brand passed Mattel as the world’s most valuable toy company and has not looked back.

If LEGO’s $1000 Death Star is for anybody, it’s for adults: a decade and a half of dedicated marketing and product development targeted at the “AFOL” (adult fans of LEGO) niche has led to a four-fold increase in grown-up buyers across the last ten years and a doubling of annual revenue since 2018. AFOLs represent millennials graduating into disposable income, nostalgic parents spoiling their kids, and fans of LEGO’s IP partnerships. And AFOLs love their Star Wars. The “kidult” millennial that grew up with the trilogy on VHS tapes (or, bless their hearts, with the prequels) represent a niche inside the niche that is routinely one of LEGO’s most popular product lines.

“LEGO has been incredibly savvy about keeping the AFOL audience. They’re making smart IP plays, and also using nostalgia a lot more. it seems like maintaining AFOL attention is their #1 business priority now, and it’s paying off,” said Akshay Guthal, who runs the popular LEGO Discord “Brickhound.”

“At this point it feels like LEGO literally can’t exist without Star Wars,” continues Guthal. The reasons for this furious fandom are plentiful, as Star Wars is a diverse enough IP to allow LEGO to attract a wide variety of fans, different-sized ships allow for many different price points and points of entry, and LEGO designers can even build the same vehicles and starships at different scales to accommodate a variety of budgets. Or minifigure completionists can set out to, say, obtain every C-P30 ever produced, and obsessive homemade model builders (they make MOCs, short for “my own creations”) can get locked-in on acquiring hundreds of Stormtroopers for “army building,” which looks like it sounds. Guthal offers that “Star Wars fans love their Glup Shittos, and LEGO definitely leans into that.”

Focusing on these niche adult builders has also led LEGO to produce increasingly elaborate display (and display-of-wealth) sets with absolutely bonkers price tags. Beginning in 2000, the “Ultimate Collectors’ Series,” or UCS, line of LEGO products was launched, featuring larger builds, designed more as models than toys, with larger price tags and typically intended for display. These became LEGO’s equivalent of tentpole summer blockbusters—sets that generate speculation, hype, and fanfare around release days. The UCS line also set the stage for LEGO to introduce high-priced sets across other IP, like Marvel and Lord of the Rings. May I interest you in a hobby that gives you the option to buy a $700 construction crane? Perhaps a $680 Titanic for these trying times?

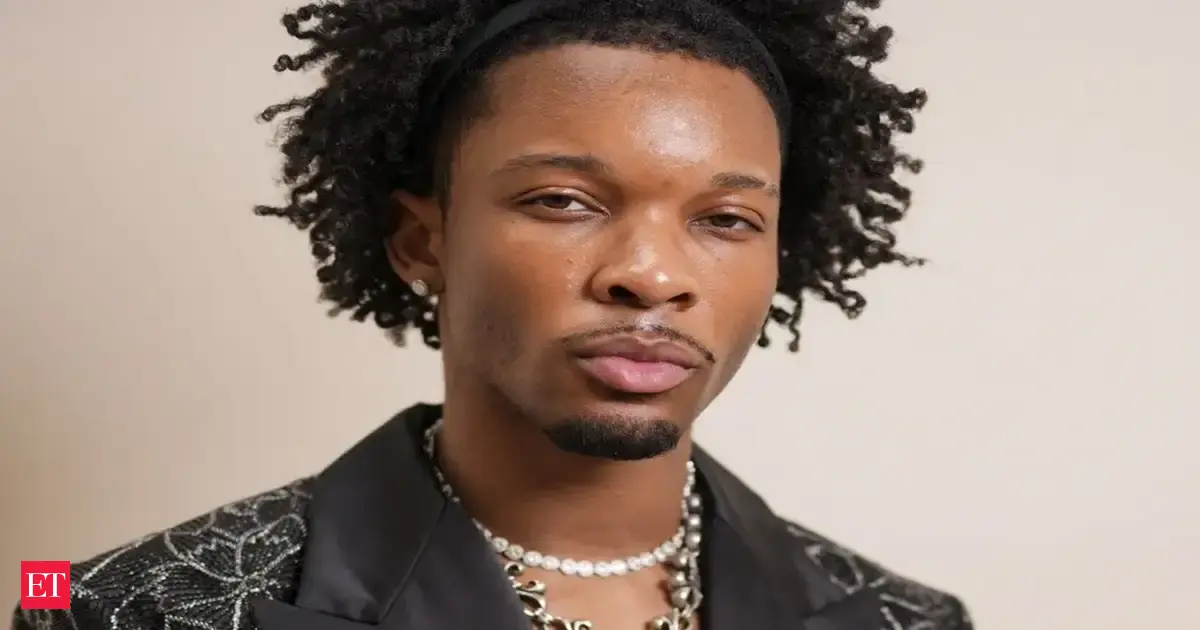

“LEGO has always been an expensive premium toy, but over the last few years especially, it feels like everyone has been feeling the prices more,” one moderator of both the r/lego and r/legostarwars Subreddits told me. This mod, who goes by the handle CX52J, has observed a tension between younger fans that are relatively new to the LEGO Star Wars community and the reality of the cost of fandom. “With the cost of living crisis and inflation rapidly raising the price of sets,” CX52J suggests, “I think many people in the community are feeling priced out of their hobby.” In his video covering the announcement of the Death Star, LEGO YouTuber “Jang,” real name Bamidele Shangobunmi, is even less inclined to mince words, stating that “LEGO hyperfans have a tremendous amount of money, and the company is happy to take that money from them.”

In the 25 years of licensed LEGO, fans have developed the theory of the “Star Wars tax,” which suggests that LEGO passes the hefty cost of IP licenses onto the consumer, Star Wars being the most notable example. There is correlation between prices and other factors, like weight and piece count, but CX52J points out to me that “shrinkflation” is also a major factor. As LEGO has “transitioned to making smaller pieces so sets can be made to look more detailed,” the result is a set that looks better, but by other metrics and comparisons is both smaller and more costly than LEGO fans are used to. CX52J even shared a chart comparing the differences between LEGO “turbo tanks” over the years. Mescad, another moderator of the r/LEGO subreddit and collector for over 30 years, agrees: “On paper we may be buying the same number of pieces as before, but it feels like less stuff for the same amount of money, and that feels bad.”

The most expensive set to this point has been the UCS Millennium Falcon, originally $800 and now $850, and widely considered to be a masterpiece by fans. The Falcon is the kind of set that is —if you believe anything could be—worth a month’s rent and rearranging your living room to display. The leak and subsequent announcement of the upcoming $1000 set sent more than a murmur through LEGO fan communities, but most of the biggest personalities in the LEGO world agreed that the eventual arrival of the set was not unexpected. David Hall, who runs the popular YouTube channel Solid Brix Studios, told me, “I don’t think it’s absurd for LEGO to make a $1000 set. There is an inherent audience out there. It’s niche, it’s small, but it’s there.”

The cycle of hype surrounding any LEGO Star Wars release follows a fairly predictable sequence of events. Retailers need to be able to easily order and reorder specific items from a large inventory, and so companies like LEGO assign every product a unique SKU (stock keeping unit). These SKUs are shared with retailers far in advance of a set’s release, and typically only convey information like the set’s cost and product line. But when an LEGO-crazy employee at Target or another big-box retailer acquires the list of these advance SKUs, leaks happen. The placeholder SKU for a standard LEGO City set that ends up being a $25 race car or ice-cream truck is not very interesting to very online AFOLs. But when something like the December 2024 SKU leak lands online (75419, UCS Death Star, $999.99), AFOLs everywhere take notice.

The next moments are by far the most dangerous for expectations and eventual outcomes, especially with a group as persnickety and detail-oriented as LEGO Star Wars fans. We’re talking about months of wild, unverified speculation. Given a price point and product line, LEGO devotees can rush to fill the void with a few knowns and little else. When the $1000 Death Star news came across the wires, posts like “If lego [sic] wanted to break the $1000 barrier, it’s the Death Star that gives them the backing,” and “Begun, the price raises have” (plus many variations of “It’d better be able to actually destroy a planet with that price tag”) swarmed the landscape of LEGO Reddit and Discords and social media. Later, in his eventual review of the set, Hall would point out the perspective that permeated: “If you’re spending $1000, you should get the best of what LEGO offers in their lineup.”

And LEGO sets, when “fairly” priced, typically cost about 10 cents per piece. This is a widely accepted rule of thumb that averages out the flashy (and expensive-to-produce) parts like transparent windshields and minifigures with the run-of-the-mill square grey bricks. LEGO reuses pieces across product lines and sets, but printed pieces (computer panels, signs, minifigure torsos) tend to be unique to individual sets. To save money, LEGO often includes sheets of stickers in lieu of printed pieces. Stickers are difficult to attach and degrade over time, which drives die-hard LEGO fans nuts. A premium product, they figure, needn’t cut corners, and in their imaginations, the $1000 Death Star certainly would not.

So doing the napkin math on a $1000 set, fans concluded that the upcoming Death Star would probably have somewhere in the neighborhood of 9,000-10,000 pieces. From this, online AFOLs began making scale and size estimates, guessing at the number of included minifigures, building their own mock-Death Stars, or simply venting about the cost, often expressing the ambient worry that LEGO was, say, “getting too comfortable with these prices.” Industrial designer and LEGO superfan Jake Brosius pointed out to me that the cost unfortunately became a framing mechanism to justify complaints and criticism: “If it were $800, I’d imagine a big part of the fanbase would still argue it should’ve been $700—or even $600. Pricing conversations have shifted a lot around LEGO lately, but I also think many people are still comparing things to 2015 instead of recognizing that costs across the board have gone up.”

Mescad, watching the LEGO Subreddit daily, agrees, describing “the disgruntled fan,” who has “pored over every screenshot, video review, and catalog photo for months learning every detail about a massive set. And [if] LEGO omitted a tiny detail, they’re angry. They are angry about the set. They are angry about the price. They are even more angry that you aren’t angry and may be considering buying the set. Some of this is legitimate, but far more often, those fans were never planning to buy the massive set anyway, and they are just looking for an excuse to feel better about missing out.“

Yet amid all the guessing and mock-ups, one design assumption held constant: the Death Star would look like the Death Star. Previous LEGO versions of the iconic space station diverged on design intention: the 2005 set is a scale model with no play features, no minifigures, and no interior, while the 2008 Death Star (and its updated 2016 version) was more like a playset, stocked with minifigures and interior environments based on iconic movie scenes. The 2016 Death Star, an open-faced diorama, topped out at about 4000 pieces, and so given that 2025’s upcoming behemoth was twice the price and more than twice the size, fans assumed that what loomed must be a perfect marriage of scale accuracy and interior wonder.

LEGO YouTuber Ryan McCullough, who runs the wildly popular MandRproductions channel, stated in April that “everything is pointing towards a big-panel Death Star with a full-on interior,” and that “it’s starting to feel like it could be an absolutely killer Death Star set. And I certainly hope so, because you can’t put a thousand dollar set out and have it be bad…”

The hype cycle was unlimited fun until July, when a new, devastating, confounding, and utterly diabolical detail emerged in the leak ecosystem: it was not going to be a sphere. The thousand-dollar Death Star, in fact, did not look like the Death Star.

“The last thing any good designer wants to do is let down the customer. We want to deliver the best possible experience,” Brosius told me. Full disclosure: Jake and I were once coworkers at the pet company BARK, where we had the pleasure of working on Star Wars–branded dog toys together. “Having to work on Lucasfilm products,” he reminds me, “there are so many factors that come into play. Cost, creative, and outside opinion all drive the product more than we’d like but that’s the job we fill. You can’t always get things exactly perfect, but you can work within constraints and optimize your solution to suit the challenges.” According to the internet, LEGO’s Star Wars team, in not making the set spherical, had dropped the ball completely.

Not unlike the producers and distributors of films and records, LEGO relies on pre-release reviews as part of their marketing plans, which means sending sets to influential builders in the LEGO Ambassador Network. This early access, plus the arrival of sets and set imagery in retail stores, allows for the final stage of leaks. A month or two after the “not a sphere” rumors began to trickle across fandom, actual images of the UCS Death Star’s box leaked on or around August 9. The design of the set was as many now feared: Instead of delivering a massive planet-shaped Death Star, LEGO had created a design that looked more like an open dollhouse, with about a dozen famous scenes from the film recreated in an assembly fans were calling the Death Slice, the Pancake of Death, or the Death Diorama. The hype cycle for the controversial set was concluding somehow with both a bang and a whimper.

César Soares, Master Model Designer at the LEGO Group and the main designer credited with the set, told me that “given we have already launched [two] LEGO Star Wars Death Star sets that we’re very proud of, we wanted this new UCS to provide a different building experience for fans.” On the record, the LEGO Group is proud of the design and the new direction. Soares explains that the dimensions and “slice” construction were all intentional, devised to impress not just in scale but in terms of ingenuity: “With the new Death Star being the largest LEGO Star Wars set by piece count to date, display was an important consideration. The flat design makes it easier to display on a shelf or against a wall, while also showing off far more of the interior than if it were a sphere. Playability has also been a key consideration too. Having already created two LEGO Death Star sets with a similar look, our designers wanted to take a fresh approach that would present both a different design and building experience.”

“My take is that designing a UCS LEGO Death Star is an impossible task,” Guthal from Brickhound told me. “LEGO designs to a price, so as soon as they assigned the $1k price tag, the set was doomed. People wouldn’t have accepted a half dome with an interior (which a lot of people wanted), because that would have been too small. The $1k price tag is what’s really putting people off about it, which is totally fair given the current economic climate, but that wasn’t a designer decision.”

Soares, for his part, is very proud of LEGO’s output: “it was actually a challenge because we wanted to have a strong display model but at the same time offer fans and builders a lot of features and playability. So, although every room is very detailed and faithful to the source material, we tried to incorporate as many play functions and Easter eggs as we could, without compromising the building experience or the sturdiness of the model.”

The official announcement from LEGO followed the leak by a few weeks, at which point fan complaints had piled up. Every other comment seemed to contain the word sphere, but beyond the disappointment with the exterior, there was much else to kvetch about: the minifigures don’t have dual-molded legs (I won’t bother explaining), there aren’t enough Stormtroopers, there are too many stickers, Darth Vader’s meditation chamber (included in the set) is not actually on the Death Star, certain scenes are rehashes of other, existing sets, and more. It seemed that for the LEGO Star Wars fandom, the set had become so large, so important, and the price-tag so emotionally overwhelming that any ordinary nitpick could become a condition to reject the toy entirely.

And quickly after announcement, members of the LEGO Ambassador Network were beginning to publish their reviews. “This isn’t feeding that itch we have for that giant ball,” Hall explained on Solid Brix Studios. On the BrickFanatics channel, the reviewer explained that for “something that’s breaking the $1000 barrier, it has to be absolute perfection,” and going on to say that “the more you build this, the more you live with it, cracks unfortunately begin to appear.” The issue, many began to pinpoint, was that when you build an oversized Titanic or Millennium Falcon set, the vehicle or building begins to appear before you. The sense of wonder and completion that accompanies a build experience includes you, the fan, looking at the product coming to life. The fans’ over-emphasis on the Death Star’s non-spherical design was maybe not just fussy personal preference, but an example of LEGO missing the plot. What’s the point of building a LEGO Death Star, if at the end you don’t have a thing on your shelf that looks like the Death Star?

Positive reviews from the Ambassador Network were also met with outsize skepticism, seemingly anticipated by the creators, who of course get to keep their free $1000 Death Stars after reviewing. The creator that posts at Jeansversion stated in her review “I have no doubt in my mind that the comments will flood in saying how easy it is to like something when you didn’t pay for it,” and over on the DUCKBRICKS channel, the same was echoed: “People are going to be even more skeptical of LAN [LEGO Ambassador Network] reviewers because they got it for free and got it early.”

It seemed the UCS Death Star, still not even a toy available for retail purchase, could not catch a break or a fair shake. Jang, who doesn’t accept free sets on his page in an attempt to stay unbiased, was more blunt: “This whole thing just doesn’t give me much of an emotional response. There it is, and that’s how much it costs. I don’t feel jealous of people who’re gonna be able to get it.” He continued: “I will use my thousand dollars towards a lot of other things instead.”

I get it. As a lifelong fan of LEGO I can recall my own red-eared childhood shame when I got old enough to kind of understand the value of money and realized that my favorite toy was the most expensive on the aisle. The Christmas lists I’d been handing my parents for years were composed entirely of wishes for high-priced pirate ships and extravagant wild-west saloons whose component parts would litter our bedroom floor, lying in wait for the bare feet of my parents. The prices of all this LEGO were far in excess of the kind of money my family spent on much else, but as it turns out, the $100 LEGO schooners and $150 train stations ($200-300 today, with inflation) I’d begged my folks for were nothing compared to what LEGO would have in store for me and my Millennial counterparts by 2025. We perhaps need a new word for this sticker shock—“MSRP trauma,” maybe, or “cost astonishment”—to accompany LEGO’s upcoming blockbuster release.

The eventual outcome of the UCS Death Star’s assault on personal toy budgeting won’t be immediately obvious, but there will be signs, says Hall: “If we’re seeing it sold out on LEGO.com or back ordered, or all the LEGO stores have across the country have fans lined up, and there’s no Death Stars by the end of the day on October 1, then I guess LEGO was right. But if there is plenty left over at the end of the day on October 1, and there’s plenty of allocation available, then I think it’ll be pretty clear that they probably took a step too far here.”

Many fans have messaged Hall personally to say they weren’t going to be buyers—that, essentially, they had the $1,000 saved up, and the set has disappointed them. Brosius offers a counter: “I don’t think there’s anything LEGO realistically could have done here to satisfy everyone. In this case, rumors ran wild in the months up to release and a lot of fans built false hopes. I think what LEGO actually delivered here is pretty innovative.”

He continues: “Spending $1,000 on anything, especially in a hobby, should be a carefully considered decision. If the price is too much of a deterrent, there’s nothing wrong with saving your money and putting it toward something you find more meaningful.” For the devoted adherents of LEGO Star Wars, finding that more meaningful purchase may be a problem outside of what one premium toy company is willing to offer.