Copyright The Boston Globe

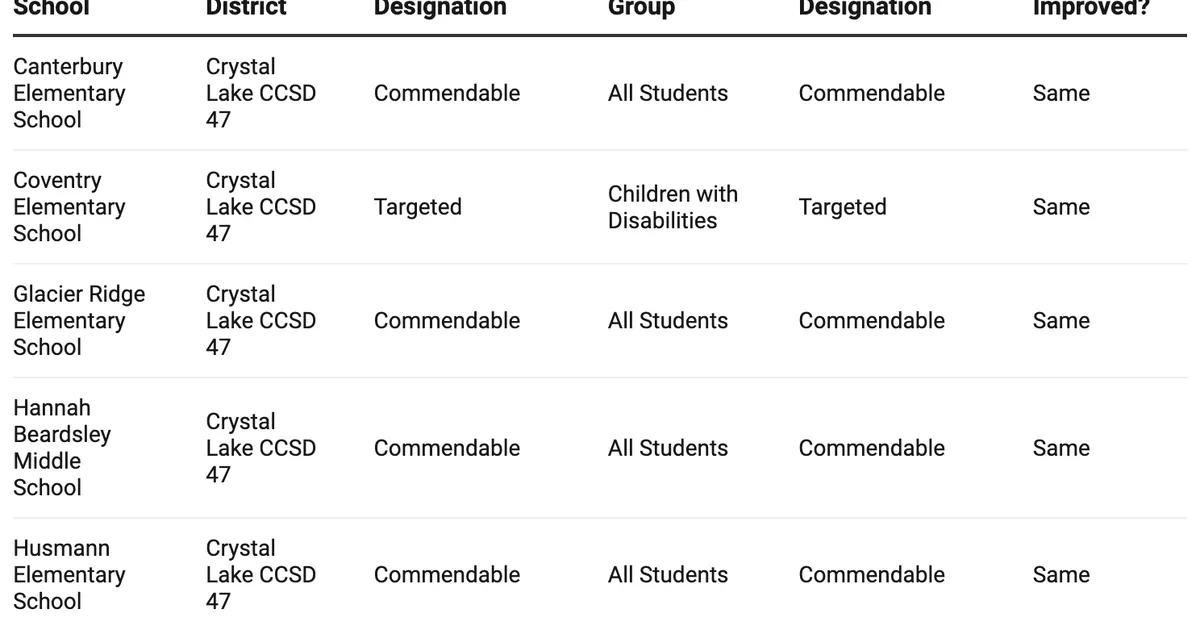

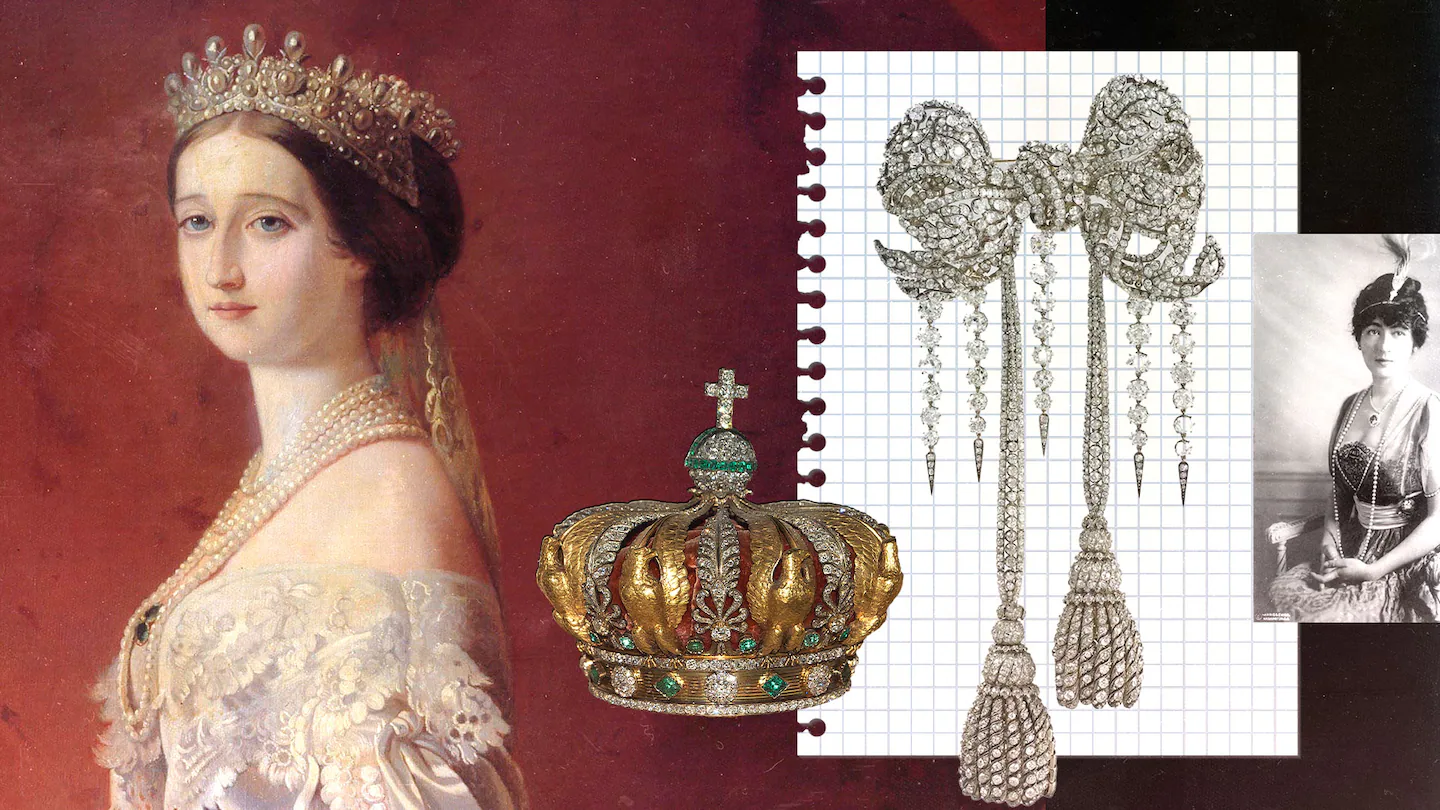

Until, that is, just days after the 20-year statute of limitations on crimes committed during the Revolution expired. That’s when a breathtaking blue diamond — flawless, about the size of a walnut — appeared on the market in London in 1812. That stone is widely believed to have been cut from the one stolen during the Revolution. Once sold, the diamond disappeared again until 1839, when it was discovered in the London collection of the recently deceased Henry Philippe Hope, gem enthusiast and scion of a Dutch banking family. Sold again (and perhaps again), the diamond eventually ended up dangling above the decolletage of an American gold mining heiress, the socialite Evalyn Walsh McLean, who wore it until her death in 1947. Enter jeweler Harry Winston, who snapped it up in 1949 and donated it to the Smithsonian Museum in 1958, where the Hope Diamond remains on view today. If this is the story of just one of the French crown jewels, consider that each of the eight pieces snatched from the Louvre Museum on Oct. 19 represents an odyssey of its own. Every facet reflects a history of war, conquest, cultural enlightenment, artistic achievement, glory, and decline. If they’re never recovered, the unique tale each tells ends, too. That’s why the crown jewels matter. The sensational (if sloppy) robbery at the Louvre provoked a worldwide heist mania. How could it not? What better made-for-Hollywood news is there than a daring daytime jewelry nab at the world’s most important art museum? Except, this isn’t just the story of a Big Screen-ready crime (not quite) worthy of France’s fictional gentleman jewel thief Arsène Lupin. It’s a story about history, and patrimony, and objects whose value, like the Hope Diamond and the French Blue before it, transcends their worth in hard currency because of the stories they evoke about the lives and the times of those who wore them. And it’s about what they represent — monarchist sympathies or antipathies aside — to the country that dearly wants them back. Today, it stabs at the heart to look up the stolen jewels on the Louvre’s website. Non exposé, the “Current Location” reads. Not exhibited. Yes, we all know why. If only we knew where. The Galerie d’Apollon, from which the crown jewels were stolen, was created to the specifications of the excess-loving King Louis XIV. The Sun King wasn’t kidding: Beneath a soaring vaulted ceiling, the room is bathed in natural sunlight. Even on a cloudy day, the entire 100-foot-long salon appears aglow, a trick of gold and good lighting. Look up and see intricately painted scenes of Apollo in his chariot racing across the heavens. The jewels were snatched from display cases installed in 2019 during a renovation of the lush jewel box of a salon. The new vitrines, created by the French jeweler Cartier, were themselves a kind of bijou — lit to give every stone a star turn. They were grouped so that it was impossible not to conjure the collective sweep of the jewels’ history. But for me, it’s all about the women who wore them. Marie-Amélie, the last queen of France. She was 11 when her aunt, Marie-Antoinette, was sent to the guillotine. The memory died hard, making Marie-Amélie reluctant to flaunt her jewels, lest the French people turn on her, too. Marie-Louise, the Austrian archduchess who displaced Empress Joséphine after she failed to give Emperor Napoleon I a male heir. The arranged marriage to the French emperor helped stabilize relations between France and Austria, but when Napoleon went into exile on Elba, Marie-Louise went to her lover. Hortense, daughter of Empress Joséphine by her previous marriage to the Vicomte de Beauharnais, who lost his head, too, during the Revolution. Of Hortense’s three sons, one, Louis-Napoléon, would crown himself emperor. And Eugénie, whose terminal philanderer of a husband, Emperor Napoléon III, nevertheless relied on her as though she were a fellow statesman. While he was off suffering from a terrible bladder stone during a calamitous battle against the Prussians in 1870, Eugénie was running the government. All this is to say nothing of the fact that some of the stolen crown jewels had landed in private hands for more than a century and were only just bought back by the French state and put on display at the Louvre in the last few decades. Did I mention an odyssey? Now gone: A matched set, or parure, featuring a diamond and sapphire diadem (24 sapphires, 1,803 diamonds), necklace, and one of the earrings worn first by Hortense de Beauharnais, when she was queen of Holland (then part of the French empire), and worn next by Marie-Amélie. Also taken: A necklace (32 emeralds, 1,138 diamonds) and earrings from the emerald set of Empress Marie-Louise. Vanished: Jewels belonging to the Empress Eugénie, including a pearl and diamond tiara (212 pearls, 1,998 diamonds, 992 rose-cut diamonds), a tasseled diamond corsage bow (2,438 diamonds, 196 rose-cut diamonds), and a reliquary brooch heavy with diamonds that would dwarf hazelnuts. Two of them are especially precious, having come from a collection of 18 diamonds bequeathed by Cardinal Mazarin upon his death to King Louis XIV. These so-called Mazarin diamonds had been part of the French national collection since 1661. Somehow spared from the frenzy of the Revolution’s smash and grab, they were not so lucky this time. The only grace note, if we can call it that, is that the Louvre thieves, in addition to leaving behind their DNA, dropped a ninth item in their haul: Eugénie’s crown (1,354 diamonds, 1,136 rose-cut diamonds, 56 emeralds). Monsieur Lupin would never have committed such gaffes. I have visited the crown jewels in the Galerie d’Apollon many times, most recently in September. (It was the same day, coincidentally, that a 24-year-old woman from China boosted $1.7 million in gold from the National Museum of Natural History, sending a little heist frisson across the Seine to the Louvre. The woman has since been arrested; the gold found in her possession had already been melted.) And the reason I never miss either the jewels or the blindingly opulent apartments of Emperor Napoléon III, also at the Louvre, is not that I’m mad for gems or gilding. It is because I can’t get enough of the secrets those sparkling accessories and rooms keep. Oh, the shenanigans they’ve seen. Paramours and a coup d’état and court intrigue — and that was just one emperor. The story of the crown jewels begins in 752, with Pépin le Bref, or Pepin the Short, whose bejeweled scepters and orbs and necklaces and crowns became symbols of France’s power — and artistry. Almost eight centuries later, in 1530, François I, prodigious art lover and patron of Leonardo da Vinci, among other Renaissance artists, decreed that the crown jewels be inventoried — weighed, measured, accounted for — upon each transfer to a new monarch. Thus the official property of the Treasury of France, not the individual monarch or ruler, the jewels became more than symbols of the nation’s wealth; they were guarantors of it. A last-resort sale of the precious gemstones, if ever such a circumstance as war, plague, or other catastrophe warranted it, would keep the French state solvent. French rulers across the centuries were free to pluck diamonds, pearls, emeralds, and sapphires from the national Treasury and set court jewelers loose to chase their fancy. The crown jewels were thus mixed and matched, their settings modified according to the fashions and whims of the day. The same stone might bejewel a king’s hilt in one era and be suspended from a silk ribbon tied tight around another monarch’s throat in the next. A bespoke tasselled bow might begin its gleaming existence as part of a belt encrusted with 4,000 diamonds and then be modified, as Empress Eugénie did with hers, into a corsage. Perhaps no one used the Treasury like a personal jewelry box more than Napoléon III and the Empress Eugénie. A devout Catholic, fashion setter, and promoter of girls’ education, among other ahead-of-her-time causes, Eugénie left in her wake the scent of Parma violets — but she never shrank like one. For nearly two decades, the imperial couple presided over a glittering new dawn for Paris. It was during their reign that the city was blessed by the twin miracles of indoor plumbing and the Palais Garnier opera house — for starters. But it was a time of paradoxes, of splendor and misery, of ostentation and poverty. The bejeweled empress must have shone so hard, she could have lit up the night sky. Her gems no longer here to tell us, I offer a pit-stop history of the Second Empire they witnessed. On Dec. 10, 1848, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, running on some serious name recognition, won by a landslide the first-ever election for the French presidency, a victory that nevertheless did not persuade the Paris elite. “He looks like a ringmaster who has been sacked for getting drunk,” sniffed the writer and cultural critic Théophile Gautier. The nephew of Napoléon I, the younger Bonaparte was initially hard to take seriously, especially when he donned the same Grande Armée uniform that had made his uncle look so stately and commanding. The green coat, white britches, high boots, bicorn hat, and Legion of Honor sash only made Louis-Napoléon’s short legs look shorter. But history reminds us that we underestimate a buffoon with popular appeal at our peril. Louis-Napoléon, disliking the prospect of submitting to another democratic election in 1852, opted to make the job a permanent position. On Dec. 2, 1851, the anniversary of his uncle’s coronation as emperor, Louis-Napoléon seized Paris in a bloody coup d’état, stunning his political opponents. A tumultuous year to the day later, Louis-Napoléon proclaimed the Second French Empire and fashioned himself Napoléon III. On Jan. 30, 1853, he married Eugénie de Montijo, who wore the diamond and pearl tiara — now stolen — that the emperor had commissioned the court jeweler to create for the occasion. For a time, the new emperor thrilled a populace that had grown tired of his predecessor, their lackluster citizen-king. Marie-Amélie’s husband, Louis-Philippe had a pear shape and perpetual lack of oomph that hurt the national self-esteem. For them, Napoléon III represented the best of his uncle’s years of charisma and conquest, prosperity and providence. Until he didn’t. When Nicolas Chamfort, the 18th-century aphorist, wrote, “Paris is a city of gaieties and pleasures where four-fifths of the inhabitants die of grief,” he could have been writing about the Second Empire. Sex, spectacle, vulgarity, materialism — the partying elite of the Second Empire collected the whole set. While every night featured a fête imperiale at the Tuileries or some other palace, the working poor were pushed out of the city center to make way for Baron Haussmann’s grand boulevards and the emperor’s ambitious public works. Victor Hugo, writing from exile in the British Isles, excoriated and made fun of the emperor in equal measure. He published a mocking pamphlet, banned but smuggled into France anyway, called “Napoléon le Pétit,” or “Napoleon the Little.” He wrote a book of poems, “Les Châtiments,” “The Castigations,” decrying the emperor’s autocracy and the inequality and poverty that proliferated and festered under it. In 1870, the empire fell following France’s humiliating defeat in the Franco-Prussian war. A revolutionary government, the Commune, seized power with the support of national guard troops who had defended Paris during the disastrous war. The soldiers hailed largely from the working classes — the wealthy could buy their way out of conscription — and they and their families had lost too much. They’d had enough. An anti-imperial fever swept France. Against a backdrop of so much gilt, the most destitute Parisians had nearly starved to death during the war. Less than a year later, during the Commune, when zoos could not feed their animals, the rich ate them. One menu during the terrible winter of 1870 to 1871 featured elephant soup, roasted camel, and kangaroo stew. Street vendors hocked the carcasses of cats, dogs, and rats to the rest of the populace. By spring 1871, the emperor and empress in exile, Paris was burning. Beleaguered Parisians setting foot for the first time in the seized Tuileries Palace could not believe the splendor. It enraged one man so much, he set off an explosion that burned it to the ground. Four years later, the democratically elected government of the Third Republic was in place. To ward off a feared coup d’état by royalists, republicans embraced an almost absurd axiom: No crowns, no kings. The crown jewels had to go. They were “stones waiting for the monarchy’s restoration,” one republican National Assembly member called them. And so, over several days in May 1887, almost all of France’s remaining crown jewels were sold at an auction that caused a global sensation without netting nearly the sum that the French Treasury had hoped for. Newspapers around the world reported on what sold to whom and for how much. “Lot 29 of the crown jewels … which was sold to Mme. Gale on Saturday, has been purchased from that lady by Tiffany,” cabled a correspondent for The New York Times. Indeed, Charles Lewis Tiffany of Tiffany & Co. in New York bought more than a third of the 77,000 stones on offer. His Gilded Age buyers, among them J.P. Morgan and Cornelia Bradley-Martin and her British aristocrat husband, could not claim them fast enough. Thus, Empress Eugénie’s tasseled diamond bow was not plundered by revolutionaries in 1887. It was sold by the French state to jeweler Emile Schlessinger, who in turn sold it to American heiress Caroline Astor. What a shockingly banal outcome in a country habituated to lurching from one dramatic denouement to another. Created for Eugénie and displayed in Paris at the Universal Exhibition of 1855, the tasseled bow reportedly made an appearance when Eugénie wore it during a reception with England’s Queen Victoria that same year. In 1902, the Duke of Westminster bought it. The Louvre Museum has worked for decades to bring home the crown jewels that were dispersed at that beheading of a sale in 1887. It was only in 2008, with funding from the Société des Amis du Louvre, that the French state was able to buy back Eugénie’s tasseled diamond bow for a reported $10.5 million. Now it’s gone again. Two thieves and five others, including one the Paris prosecutor identifies as the prime suspect, are in custody, but the jewels remain at large. Every heist consists of at least two crimes: the theft and the fencing of the loot. By now, for all we know, the 2,438 diamonds and 196 rose-cut diamonds from Eugénie’s single tasseled diamond bow, to take just one of the pieces, could already have been prized from their settings and cut beyond recognition into modern shapes. Some of the gems, like the erstwhile French Blue, are so large, a single one could yield multiple stunners. They will still be beautiful. They will still be coveted. Diamonds are forever, after all, even if their status as royal stones isn’t. The story of the heist is one for the ages. But it’s the jewels themselves that spellbind.