Copyright Baton Rouge Advocate

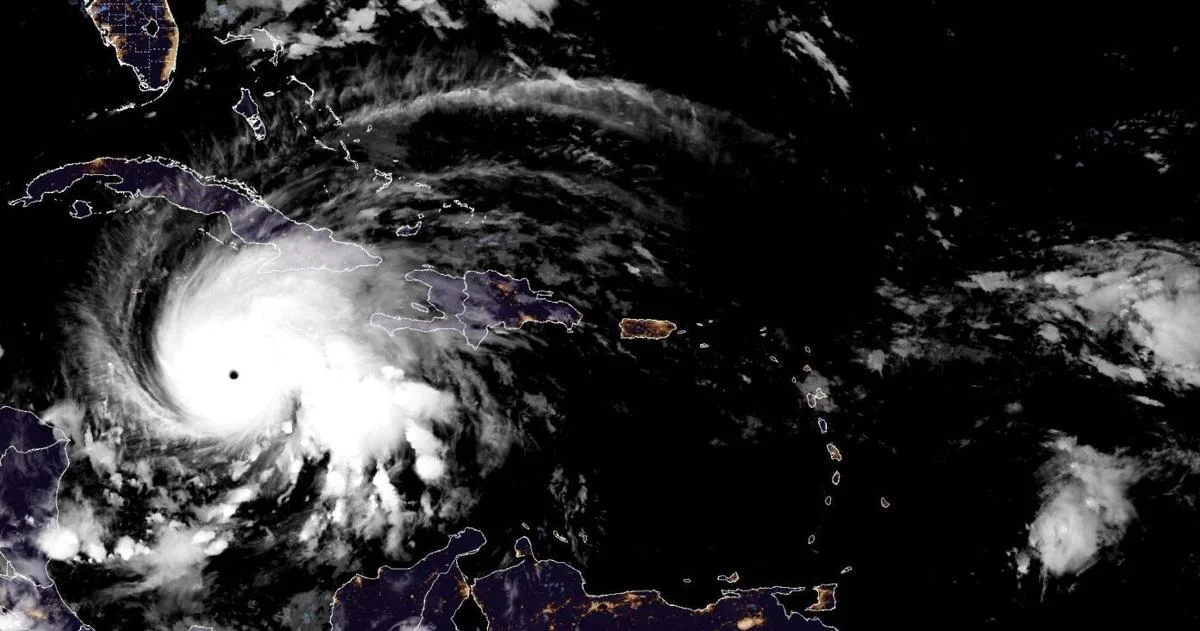

With wind speeds that reached a whopping 185 mph by Tuesday morning and rainbands that could flood the Caribbean with feet of water, Hurricane Melissa will likely go down as the most devastating Atlantic storm of 2025 and among the strongest ever to hit Jamaica's shores. But when Melissa first formed last week, it made history in another way: It was the first named storm of the year to make it into the Caribbean Sea, where, despite warmer than average waters, things have been eerily quiet this hurricane season. Only two named storms, Melissa and Tropical Storm Barry, have tracked through the Caribbean or Gulf so far this year, less than half the historical average, according to Colorado State University hurricane researcher Phil Klotzbach. From 1991 to 2020, Klotzbach said the Atlantic produced an average of about six named storms that tracked through the Caribbean or Gulf each season, whether they were "homegrown" storms or systems that started as tropical waves farther east in the Atlantic. Last season produced nearly twice the average, with 11 named storms that either formed over or tracked through the Caribbean or Gulf. State Climatologist Jay Grymes said it's not unheard of for an Atlantic season to end having produced just one or two storms in the Gulf, and this year's merciful lack of activity in the region can be attributed to a couple of obvious environmental factors — and others that are not so obvious. But Grymes said the last 25 years have been brutal for Louisiana in terms of tropical activity, the busiest on record for the Bayou State since record keeping began in the 1850s. That, he said, more than anything has made this year feel abnormal. "We have become hypersensitive in the central Gulf Coast. And it's not just the last couple of years, it's the last two decades." Grymes said. "It's more about psyche than it is about the atmosphere sometimes." The year of the fish storm Still, the atmosphere has certainly played its role this season, too. Despite near record high sea-surface temperatures in the Gulf and temperatures hovering around the mid to upper 80s in the Caribbean, Grymes said warm water is just one of many criteria needed to fuel tropical storm formation and growth. "The real driver for storms is the atmosphere," he said. A vast majority of this year's 13 named storms started as seeds west of Africa and then curved away from the U.S., most avoiding direct hits to land, thanks to what meteorologists call the "Azores high," a semi-permanent ridge of high pressure over a portion of the Atlantic Ocean that steers tropical systems. Grymes said the high-pressure ridge expands and contracts in a cycle throughout the year, and its phases are known by two names: the Bermuda and Azores high. In its expanded, Bermuda phase, the ridge stretches so far west across the Atlantic that it sometimes reaches the U.S. East Coast or Gulf, creating a barrier that forces tropical systems to move low along its rim. That can result in the kind of long-track storms that start near Africa and go on to complete the more than 3,000-mile trek across the ocean and into the Gulf. But Grymes said the ridge has been in its contracted, Azores phase for much of this season, allowing systems to turn north well before reaching the U.S. Little homegrown Dry air that hampers storm formation contributed to a lull in activity in the tropical Atlantic late this summer at what is normally considered peak season, Grymes said. It's likely that similar conditions have prevented systems from bubbling up on their own in the Caribbean and Gulf, too. Grymes said a certain set of factors — warm water, a mechanism that can create a cluster of storms, an environment conducive to strengthening — need to coincide for a system to get a storm to pop up on its own in the Gulf. For whatever reason, those things just haven't come together so far this year. "There's no real clear explanation," he said. "But even homegrown storms often have a tropical that's come in from the east and then that wave starts to get organized." Jill Trepanier, a professor and hurricane researcher at LSU, agreed, saying dry air and wind shear have posed a persistent problem for systems brewing in the warm waters of the Caribbean and Gulf this year. But Trepanier also said its typical for homegrown formations in the Caribbean and Gulf to pick up later in the season, generally by September, as conditions across the rest of the Atlantic grow increasingly hostile to storm formation. While water temperatures have usually dropped and wind shear has intensified throughout much of the Atlantic by this time of year, parts of the Gulf and Caribbean are ready to burn. "And so Melissa is a good example of that," Trepanier said. Echoing Grymes' point, Trepanier said this year likely feels stranger than it is to many Louisianans in comparison to recent, hyper-active seasons.